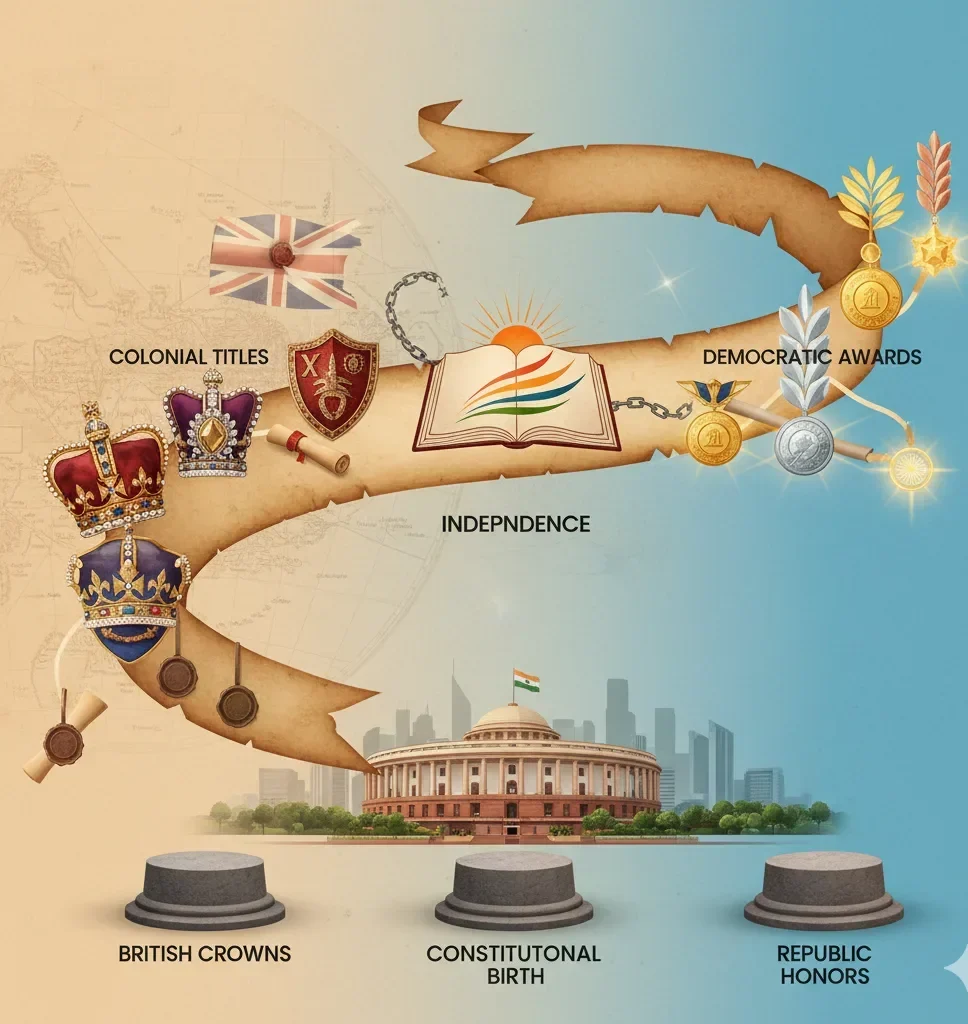

Have you ever wondered why Indians cannot use titles like “Sir” or “Maharaja” before their names today? Or why our Constitution specifically prohibits the government from creating a class of nobility through titles? The answer lies in Article 18 of the Indian Constitution—one of the most fascinating yet underappreciated provisions that quietly ensures equality in our democratic republic.

When India gained independence in 1947, the framers of our Constitution were acutely aware of how the British colonial system had used titles to create artificial hierarchies and foster loyalty among Indians. Titles like “Rai Bahadur,” “Khan Bahadur,” and “Sir” weren’t just honors—they were instruments of social stratification that divided Indians into privileged and non-privileged classes.

Article 18 represents our nation’s conscious decision to reject these colonial remnants and embrace true democratic equality. But here’s what makes this provision truly remarkable: while it abolishes titles that create social hierarchy, it doesn’t stop the nation from recognizing genuine merit and service. This delicate balance between preventing artificial distinctions and acknowledging real contributions makes Article 18 a masterpiece of constitutional drafting.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore every aspect of Article 18—from its historical origins to its practical applications today. Whether you’re a law student, civil services aspirant, or simply a curious citizen, you’ll discover why this seemingly simple article is actually one of the most important guardians of equality in modern India.

Table of Contents

Article 18: The Bare Provision

Let’s start by examining the actual text of Article 18 as it appears in our Constitution:

18. Abolition of titles

(1) No title, not being a military or academic distinction, shall be conferred by the State.

(2) No citizen of India shall accept any title from any foreign State.

(3) No person who is not a citizen of India shall, while he holds any office of profit or trust under the State, accept without the consent of the President any title from any foreign State.

(4) No person holding any office of profit or trust under the State shall, without the consent of the President, accept any present, emolument, or office of any kind from or under any foreign State.

Quick Takeaway: Article 18 creates a four-layered protection system—preventing the Indian state from creating titles of nobility, stopping Indian citizens from accepting foreign titles, and ensuring that both citizens and non-citizens in government positions remain free from foreign influence through titles or gifts.

Understanding Article 18 – Definition and Scope

What Makes Article 18 Unique?

Article 18 stands out among fundamental rights because it’s primarily a restrictive provision rather than a rights-conferring one. Unlike other articles that grant rights to citizens, Article 18 places limitations on both the state’s power and individual actions.

Did You Know? Article 18 doesn’t actually protect any fundamental right in the traditional sense. Instead, it acts as a constitutional safeguard that limits executive and legislative authority to create or recognize titles that could undermine equality.

The Democratic Philosophy Behind Article 18

The provision embodies three core democratic principles:

- Social Equality: No artificial distinctions based on state-conferred honors

- National Sovereignty: Protection from foreign influence through titles

- Merit-Based Recognition: Allowing recognition of genuine achievement without creating hierarchy

The Four Clauses of Article 18 Explained

Clause (1): The State Cannot Create Titles

“No title, not being a military or academic distinction, shall be conferred by the State.”

This is the heart of Article 18. It prevents the Indian government from creating titles that could establish social hierarchy or nobility.

What’s Prohibited:

- Hereditary titles like “Maharaja” or “Nawab”

- Colonial-era honors like “Rai Bahadur” or “Khan Bahadur”

- Any title suggesting social superiority or rank

What’s Allowed:

- Military honors (like Param Vir Chakra, Ashok Chakra)

- Academic distinctions (like Doctor, Professor)

- Civilian awards that don’t function as titles (Bharat Ratna, Padma awards)

Quick Takeaway: The state can honor citizens for exceptional service, but cannot create a titled aristocracy or privileged class through these honors.

Clause (2): Citizens Cannot Accept Foreign Titles

“No citizen of India shall accept any title from any foreign State.”

This provision ensures that Indian citizens remain free from foreign allegiances that could compromise their loyalty to India.

Practical Examples:

- An Indian citizen cannot accept a knighthood from the British Crown

- Indian diplomats cannot accept titles from countries where they serve

- Even honorary titles from foreign universities may need scrutiny if they function as nobility titles

Clause (3): Non-Citizens in Government Need Presidential Approval

“No person who is not a citizen of India shall, while he holds any office of profit or trust under the State, accept without the consent of the President any title from any foreign State.”

This clause covers foreign nationals working in Indian government positions, ensuring their loyalty isn’t divided.

Clause (4): No Foreign Gifts Without Permission

“No person holding any office of profit or trust under the State shall, without the consent of the President, accept any present, emolument, or office of any kind from or under any foreign State.”

This extends beyond titles to cover all forms of foreign inducements—gifts, money, or positions—that could compromise officials’ integrity.

Quick Takeaway: Clauses (3) and (4) work together to ensure that anyone serving the Indian state—citizen or non-citizen—remains free from foreign influence through titles, gifts, or other inducements.

Purpose and Historical Context

Why Article 18 Was Necessary

The constituent assembly’s decision to include Article 18 wasn’t arbitrary—it was a direct response to the colonial experience that had scarred Indian society for centuries.

The Colonial Title System: A Tool of Division

Under British rule, titles served multiple purposes:

- Creating Loyal Elite: Titles like “Rai Bahadur” and “Khan Bahadur” were given to Indians who showed loyalty to the British Empire

- Social Stratification: These titles created artificial hierarchies, making some Indians feel superior to others

- Psychological Control: Recipients often became more invested in preserving British rule to maintain their privileged status

Historical Example: The British systematically used titles like “Rai Bahadur” (for Hindus), “Khan Bahadur” (for Muslims), and “Sardar Bahadur” (for Sikhs) to create a class of Indians whose interests aligned with colonial rule rather than national independence.

The Framers’ Vision

The constituent assembly members understood that democracy cannot function properly when artificial distinctions divide citizens. As one constitutional expert noted, “Titles and titular achievements must not be granted in a democratic country. It will be counterproductive to the development of social justice”.

Quick Takeaway: Article 18 represents India’s conscious rejection of colonial hierarchies and commitment to creating a society where merit, not titles, determines one’s standing.

What Constitutes a “Title” Under Article 18

Defining “Titles” in Constitutional Context

Understanding what qualifies as a prohibited “title” is crucial for proper application of Article 18.

Titles Prohibited Under Article 18:

- Hereditary honors: Maharaja, Raja, Nawab, Begum

- Colonial distinctions: Rai Bahadur, Khan Bahadur, Rai Sahib, Khan Sahib

- Nobility indicators: Sir, Lord, Lady (when used as formal titles)

- Any designation that creates social hierarchy or suggests inherited privilege

The Supreme Court’s Interpretation

The Supreme Court has clarified that Article 18 prohibits specifically “titles of nobility” rather than all forms of recognition. This distinction is crucial for understanding why some awards are permitted while others aren’t.

Modern Applications

In today’s context, prohibited titles would include:

- Any government-created designation suggesting royal lineage

- Foreign knighthoods or lordships

- Hereditary positions that come with titles

- Religious titles when used to create governmental hierarchy

Common Confusion: Many people mistakenly believe that professional designations like “Dr.” or “Professor” are titles under Article 18. These are actually academic distinctions specifically exempted by the Constitution.

Quick Takeaway: Article 18 targets titles that create social hierarchy or suggest inherited privilege, not professional or achievement-based designations that reflect genuine qualifications or service.

Exceptions: Military and Academic Distinctions

Why These Exceptions Exist

The Constitution specifically exempts military and academic distinctions because these represent earned achievements rather than inherited or arbitrary privileges.

Military Distinctions: Honoring Valor

Permitted Military Honors Include:

- Param Vir Chakra: India’s highest military decoration for valor

- Maha Vir Chakra: Second-highest military decoration

- Vir Chakra: Third-highest military decoration

- Ashok Chakra: Highest peacetime military decoration

Why These Are Allowed: Military decorations recognize specific acts of bravery, sacrifice, or exceptional service. They don’t create a hereditary class or social hierarchy—they acknowledge individual merit and courage.

Academic Distinctions: Recognizing Scholarship

Common Academic Distinctions:

- Doctor (Dr.): Earned through advanced academic study

- Professor: Professional academic rank

- Chancellor: Academic administrative position

- Fellow: Scholarly recognition by academic institutions

The Merit Principle: These distinctions are earned through education, research, or scholarly achievement. They reflect individual capability and contribution to knowledge, not inherited status.

Key Distinction: Merit vs. Privilege

The fundamental difference between permitted distinctions and prohibited titles lies in how they’re acquired:

| Permitted (Merit-Based) | Prohibited (Status-Based) |

|---|---|

| Earned through service/achievement | Inherited or arbitrarily granted |

| Reflects individual capability | Creates social hierarchy |

| Based on specific qualifications | Based on birth, loyalty, or favor |

| Temporary/conditional | Often permanent/hereditary |

Quick Takeaway: Article 18 allows recognition of genuine achievement and service while preventing the creation of an artificial aristocracy based on birth, favor, or colonial-style loyalty.

Landmark Case Law: Balaji Raghavan v. Union of India

The Constitutional Challenge That Defined Article 18

The 1996 Supreme Court case Balaji Raghavan v. Union of India remains the most important judicial interpretation of Article 18.

Background of the Case

The Challenge: Balaji Raghavan and others filed petitions in Kerala and Madhya Pradesh High Courts, arguing that national awards like Bharat Ratna, Padma Vibhushan, Padma Bhushan, and Padma Shri violated Article 18(1) by creating titles prohibited by the Constitution.

The Petitioners’ Arguments:

- These awards constituted “titles” within Article 18’s meaning

- They created social hierarchy among citizens

- Recipients often used awards as prefixes/suffixes, making them function like titles

- The selection process was arbitrary and non-transparent

The Supreme Court’s Historic Judgment

Key Findings:

- Awards Are Not Titles: The Court held that national awards are recognitions of excellence, not titles of nobility prohibited by Article 18

- Merit-Based Recognition: These awards acknowledge exceptional service in various fields—arts, literature, science, and public service—without conferring hereditary privileges

- No Legal Rights or Precedence: Unlike colonial titles, national awards don’t grant any civil or legal rights, precedence, or special privileges to recipients

- Prohibition on Name Usage: The Court specifically ruled that recipients cannot use awards as prefixes or suffixes to their names (e.g., “Bharat Ratna Dr. X” is prohibited)

The Court’s Reasoning

Why National Awards Don’t Violate Article 18:

- Purpose: They recognize merit and service, not create nobility

- Effect: No hereditary privileges or social precedence

- Nature: Purely honorary without legal implications

- Democratic Practice: Common in democratic nations worldwide

Impact and Recommendations

While upholding the awards’ constitutionality, the Supreme Court made important recommendations:

- Better Guidelines Needed: Criticized existing selection criteria as vague and prone to misuse

- Institutional Reform: Recommended creating a high-level committee to review selection processes

- Annual Limits: Suggested caps on number of awards to maintain prestige

- Transparency: Called for clearer, more objective selection criteria

Quick Takeaway: The Balaji Raghavan judgment established that Article 18 doesn’t prohibit merit-based recognition, but such awards must not function as titles and recipients cannot use them as name prefixes or suffixes.

National Awards vs Titles: The Fine Line

Understanding the Constitutional Distinction

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Balaji Raghavan created a clear framework for distinguishing between prohibited titles and permissible awards.

Current National Awards System

India’s Civilian Honors (In Order of Precedence):

- Bharat Ratna: Highest civilian honor for exceptional service of highest order

- Padma Vibhushan: Second-highest civilian honor for exceptional and distinguished service

- Padma Bhushan: Third-highest civilian honor for distinguished service of high order

- Padma Shri: Fourth-highest civilian honor for distinguished service

Why These Awards Are Constitutional

Constitutional Compliance Factors:

- No Hereditary Element: Awards aren’t passed to descendants

- Merit-Based Selection: Given for specific achievements or service

- No Legal Privileges: Recipients gain no special legal status or rights

- Non-Hierarchical Usage: Cannot be used as titles before/after names

- Democratic Recognition: Acknowledge contributions to society

The Usage Rules

What Recipients Can Do:

- Mention the award in biographical descriptions

- Include it in lists of achievements

- Reference it in professional contexts

What Recipients Cannot Do:

- Use as prefix: “Padma Shri John Doe”

- Use as suffix: “John Doe, Bharat Ratna”

- Display it as a title on official documents

- Claim special precedence based on the award

Enforcement Mechanism

Violation Consequences: According to Regulation 10 of the award guidelines, recipients who misuse awards as titles risk losing the award through a formal review process.

International Perspective

Global Practice: Most democratic nations have similar award systems:

- United States: Presidential Medal of Freedom, Congressional Gold Medal

- United Kingdom: Order of Merit, Companion of Honour (distinct from nobility titles)

- France: Legion of Honour, National Order of Merit

- Germany: Order of Merit of the Federal Republic

The Democratic Model: These systems show that recognizing exceptional service doesn’t require creating titled aristocracy—the key is ensuring awards remain merit-based recognition rather than social hierarchy tools.

Quick Takeaway: National awards represent the constitutional balance between recognizing excellence and preventing aristocracy—they honor achievement without creating the social stratification that Article 18 prohibits.

Practical Applications in Daily Life

How Article 18 Affects Modern India

While Article 18 might seem like an abstract constitutional provision, it has real-world implications that touch various aspects of Indian life.

Government and Public Service

Official Documentation:

- Government forms cannot include title fields beyond professional designations

- Civil service positions don’t carry hereditary titles or nobility markers

- Public servants cannot accept foreign honors without presidential approval

Real-World Example: When former President Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam received the Bharat Ratna, he continued to be addressed primarily by his academic title “Dr.” rather than using the award as a prefix—demonstrating proper constitutional compliance.

Educational Institutions

Academic Recognition:

- Universities can confer degrees and academic honors

- Professional titles (Dr., Professor) remain standard practice

- Honorary doctorates are permitted as academic distinctions

- Religious or traditional titles cannot be officially recognized by state institutions

Media and Social Practice

Addressing Public Figures:

- Newspapers and media avoid using colonial-era titles

- Social respect is shown through professional or academic designations

- Traditional forms of address (ji, sahib) remain cultural, not official titles

Legal and Business Contexts

Corporate World:

- Company registrations cannot include prohibited titles in director names

- Professional designations (CA, CS, Advocate) are standard

- Foreign business honors require careful legal review

International Relations

Diplomatic Protocol:

- Indian diplomats cannot accept titles from foreign governments

- Cultural exchanges must avoid title-conferring ceremonies

- International honors require presidential consent for government officials

Common Situations Where Article 18 Applies

- NRI Communities: Indians abroad must decline foreign titles or risk constitutional issues if returning to public service

- Academic Collaborations: International scholarly honors need review to ensure they don’t function as nobility titles

- Cultural Programs: Traditional ceremonies cannot confer official titles recognized by the state

- Religious Leadership: Spiritual titles remain personal/religious, not officially recognized by government

Quick Takeaway: Article 18’s influence extends throughout Indian society, quietly ensuring that merit and achievement—not artificial titles—determine how we recognize and address each other in official contexts.

Common Misconceptions and Myths

Debunking Popular Misunderstandings About Article 18

Despite its importance, Article 18 is surrounded by several myths and misconceptions that can lead to confusion about its scope and application.

Myth 1: “Article 18 Prohibits All Forms of Recognition”

The Reality: Article 18 only prohibits titles that create social hierarchy or nobility. Merit-based recognition through awards, academic degrees, and professional designations are fully permitted.

Why This Myth Persists: Some people interpret “abolition of titles” too broadly, not understanding the specific constitutional meaning of “titles” as nobility markers.

Myth 2: “Padma Awards Violate Article 18”

The Reality: The Supreme Court in Balaji Raghavan clearly held that national awards are constitutional because they recognize merit without creating titled aristocracy.

The Confusion: Early critics argued these awards functioned as titles, but the Court distinguished between recognition of service and creation of nobility.

Myth 3: “Professional Titles Like ‘Dr.’ Are Prohibited”

The Reality: Academic distinctions like “Dr.” and “Professor” are specifically exempted by Article 18(1) as they represent earned qualifications, not inherited status.

Source of Confusion: People sometimes conflate professional designations with aristocratic titles, missing the constitutional distinction between merit-based and status-based recognition.

Myth 4: “Article 18 Applies Only to Government Officials”

The Reality: Different clauses have different scope:

- Clause (1): Applies to state conferment of titles on anyone

- Clause (2): Applies to all Indian citizens regarding foreign titles

- Clauses (3) & (4): Apply specifically to government officials and foreign nationals in government service

Myth 5: “Religious Titles Are Banned by Article 18”

The Reality: Article 18 doesn’t interfere with religious or cultural practices. Religious titles remain within their spiritual context—they simply cannot be officially recognized by the state as conferring civil precedence.

Myth 6: “Breaking Article 18 Is a Criminal Offense”

The Reality: Article 18 violation isn’t criminally punishable. It’s a constitutional limitation on state power and individual actions, enforceable through civil remedies and constitutional challenges.

Understanding the Real Scope

What Article 18 Actually Does:

- Prevents state creation of hereditary nobility

- Stops foreign influence through titles

- Maintains democratic equality principles

- Allows merit-based recognition within constitutional bounds

What Article 18 Doesn’t Do:

- Eliminate all forms of recognition or honor

- Prohibit professional or academic titles

- Interfere with religious or cultural practices

- Create criminal penalties for violations

Quick Takeaway: Most misconceptions about Article 18 stem from not understanding its specific purpose—preventing titled aristocracy while allowing democratic recognition of merit and achievement.

International Perspective

How Other Democracies Handle Titles and Recognition

Understanding how other constitutional democracies address the tension between recognizing achievement and preventing aristocracy helps illuminate Article 18’s unique approach.

The United States: Constitutional Prohibition

Article I, Section 9: “No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States”

American Approach:

- Complete prohibition on government-created titles

- Merit-based awards (Presidential Medal of Freedom) without title function

- Academic and military distinctions widely accepted

- Strong constitutional separation from European aristocratic traditions

Similarity to India: Both constitutions explicitly reject nobility titles as incompatible with democratic equality.

United Kingdom: Evolved Monarchy with Democratic Limits

The British System:

- Maintains hereditary and created peerages (Lord, Dame, Sir)

- Separates honors system from political power

- House of Lords reforms have reduced hereditary political influence

- Orders of Merit exist alongside traditional titles

Key Difference: Unlike India, Britain retained its historical title system while limiting political power of titled individuals.

France: Revolutionary Rejection and Modern Recognition

Historical Context:

- French Revolution (1789) abolished all nobility titles

- No hereditary titles in modern French Republic

- Legion of Honour and other orders recognize service without creating nobility

- Strong constitutional commitment to equality (“égalité”)

Parallel with India: Both nations consciously rejected aristocratic systems after revolutionary/independence moments.

Germany: Federal Republic’s Democratic Approach

Post-War System:

- No official recognition of former nobility titles (abolished 1919)

- Former noble titles became part of surnames only

- Order of Merit recognizes service without title function

- Strong constitutional equality principles

Constitutional Similarity: Like India, Germany’s modern constitution reflects democratic rejection of aristocratic privilege.

Comparative Analysis: Democratic Patterns

| Country | Titles Approach | Recognition System | Constitutional Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| India | Prohibited (Art. 18) | Merit-based awards | Equality and democracy |

| USA | Prohibited (Art. I.9) | Presidential awards | Democratic equality |

| France | Abolished 1789 | Republican honors | Revolutionary equality |

| Germany | Abolished 1919/1949 | Federal orders | Democratic constitution |

| UK | Retained/evolved | Mixed honors system | Constitutional monarchy |

Lessons for India

Successful Democratic Models:

- Clear Constitutional Prohibition: Works effectively in preventing aristocracy

- Merit-Based Recognition: Compatible with democratic values when properly structured

- Cultural Adaptation: Constitutional principles can coexist with cultural traditions

- International Respect: Countries without title systems aren’t less prestigious internationally

Article 18 in Global Context

India’s Unique Position:

- More explicit than most constitutions in prohibiting titles

- Balances recognition with equality better than pure prohibition models

- Reflects post-colonial commitment to dismantling hierarchical systems

- Serves as model for other post-colonial democracies

Quick Takeaway: Article 18 places India among the world’s most committed democracies to constitutional equality, using a sophisticated approach that prevents aristocracy while enabling merit recognition—a balance that many established democracies still struggle to achieve.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Can Indian citizens accept honorary degrees from foreign universities?

Answer: Yes, honorary degrees are academic distinctions, not titles within Article 18’s meaning. However, if the degree comes with a title suggesting nobility (like “Sir” or “Lord”), that would be prohibited.

2. Are traditional Indian titles like “Pandit” or “Ustad” banned under Article 18?

Answer: No, cultural and traditional titles remain part of social practice. Article 18 only prohibits state recognition of titles that create official hierarchy or precedence. Traditional titles can be used culturally but cannot carry official government recognition.

3. What happens if someone violates Article 18?

Answer: Article 18 violations aren’t criminal offenses. The Constitution provides civil remedies—citizens can approach courts under Article 226 (High Court) or Article 32 (Supreme Court) for enforcement. For national awards, misuse as titles can lead to withdrawal of the award.

4. Can Indian companies use titles in their names or for their executives?

Answer: Companies cannot register with prohibited titles in official names. Professional designations (CEO, Chairman, Director) are acceptable as they describe roles, not nobility. Traditional business titles may be culturally used but cannot carry official state recognition.

5. How does Article 18 affect Indian diaspora communities abroad?

Answer: Indian citizens living abroad cannot accept foreign titles even while residing outside India. However, they can accept professional recognitions, academic honors, or cultural awards that don’t function as nobility titles. If they plan to return to public service in India, presidential consent would be required.

6. Are military ranks considered titles under Article 18?

Answer: No, military ranks (Colonel, General, Admiral) are professional positions and military distinctions specifically exempted by Article 18(1). They represent earned positions in military hierarchy, not hereditary or arbitrary titles.

7. Can religious leaders use titles officially?

Answer: Religious titles remain within spiritual and cultural contexts. While leaders can be addressed by traditional titles within their communities, these cannot be officially recognized by the state or used in governmental contexts to claim precedence.

8. What about titles inherited from pre-independence India?

Answer: All pre-independence titles, including those from princely states or British colonial administration, lost official recognition after the Constitution came into effect. Former title holders cannot use them for official precedence, though they may retain cultural significance.

9. Can Indian citizens be knighted by foreign governments?

Answer: No, Indian citizens cannot accept knighthoods or similar foreign titles. These would violate Article 18(2) even if offered by friendly nations. Professional or academic honors from foreign countries are acceptable if they don’t function as nobility titles.

10. How are violations of clauses (3) and (4) detected and enforced?

Answer: Government maintains records of foreign gifts and honors received by officials. Annual declarations, diplomatic protocols, and internal monitoring help ensure compliance. Violations can lead to disciplinary action and constitutional challenges.

Quick Takeaway: Article 18’s scope is precisely defined—it prevents official recognition of hierarchy-creating titles while allowing cultural practices, professional designations, and merit-based recognition to flourish within constitutional bounds.

Key Takeaways

Essential Points Every Indian Should Know About Article 18

Constitutional Foundation

- Article 18 is part of Part III (Fundamental Rights) but functions as a limitation on state power rather than a citizen’s right

- It reflects India’s commitment to democratic equality and rejection of colonial-era social hierarchies

Four-Clause Structure

- Clause (1): State cannot confer titles (except military/academic distinctions)

- Clause (2): Indian citizens cannot accept foreign titles

- Clauses (3) & (4): Government officials need presidential consent for foreign titles/gifts

Legal Precedent

- Balaji Raghavan v. Union of India (1996) established that merit-based awards don’t violate Article 18

- National awards are constitutional but cannot be used as prefixes/suffixes to names

- Selection processes need transparency and clear criteria

Practical Applications

- Professional titles (Dr., Professor) and military ranks are explicitly allowed

- Traditional and religious titles can be culturally used but lack official state recognition

- Government officials must declare and seek permission for foreign honors

Common Misconceptions

- Article 18 doesn’t ban all recognition—only hierarchy-creating titles

- Academic degrees and professional designations remain fully permitted

- Cultural practices and traditional forms of address aren’t constitutionally prohibited

Global Context

- India joins USA, France, and Germany in constitutionally prohibiting nobility titles

- This places India among the world’s strongest democratic equality commitments

- Merit-based recognition systems prove compatible with democratic values

Modern Relevance

- Ensures government positions are based on merit, not inherited or purchased status

- Prevents foreign influence through title-based inducements

- Maintains social equality principles essential for democratic functioning

Quick Takeaway: Article 18 represents one of the Indian Constitution’s most successful provisions—quietly ensuring democratic equality while allowing appropriate recognition of merit and achievement, making it a model for balanced constitutional democracy.

Conclusion

As we conclude this comprehensive exploration of Article 18, it becomes clear why this seemingly simple constitutional provision deserves recognition as one of the most sophisticated pieces of democratic architecture in the world. In just four clauses and fewer than 100 words, Article 18 accomplishes what many nations have struggled with for centuries—completely eliminating aristocratic hierarchy while preserving space for genuine recognition of merit and service.

The Lasting Impact of Article 18

When India’s constituent assembly debated this provision over seven decades ago, they were addressing more than just colonial titles—they were defining the kind of society India would become. Today, we can see the wisdom of their approach. Unlike many post-colonial nations that either retained traditional hierarchies or swung to the opposite extreme of eliminating all recognition, India found a constitutional middle path that honors achievement while preventing the emergence of a privileged class.

A Living Constitutional Success

The Supreme Court’s handling of the Balaji Raghavan case demonstrates how Article 18 continues to evolve and adapt to modern circumstances. Rather than being a rigid prohibition, it has proven to be a flexible framework that can distinguish between harmful aristocracy and beneficial recognition. This adaptability ensures that Article 18 remains relevant as Indian society continues to develop and modernize.

Why Article 18 Matters Today

In an era where social media can create instant “influencers” and economic inequality generates new forms of privilege, Article 18’s commitment to preventing state-sanctioned hierarchies becomes even more important. It ensures that in at least one crucial sphere—official recognition and government service—merit rather than inherited or purchased advantage determines outcomes.

The Democratic Example

Perhaps most remarkably, Article 18 has achieved its goals without creating the problems many feared. Critics worried that prohibiting titles would somehow diminish India’s ability to honor exceptional citizens or reduce the nation’s prestige internationally. Instead, India’s approach has enhanced both democratic credibility and the meaningful value of recognition when it is given.

Looking Forward

As India continues its journey as a democratic republic, Article 18 provides a stable foundation for equality while remaining flexible enough to accommodate new forms of recognition that genuinely serve democratic values. Whether in emerging fields like technology, environmental science, or social innovation, the constitutional framework allows appropriate honor without creating inappropriate hierarchy.

The Enduring Promise

Article 18 embodies a simple but powerful promise: in the Republic of India, your worth is determined by your contributions, character, and capabilities—never by titles, birth, or artificial distinctions. This promise has been kept for over seven decades and continues to shape a more equal and democratic society.

For every Indian who dreams of being recognized for their achievements rather than their background, Article 18 stands as a constitutional guardian, ensuring that merit, service, and genuine contribution remain the only paths to honor in our democratic republic.

What do you think about Article 18’s role in modern India? Have you encountered situations where this provision has practical relevance? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below, and let’s continue this important conversation about constitutional equality and democratic recognition.

Author Bio

Legal Content Specialist | Constitutional Law Researcher | SEO Content Creator

With extensive experience in Indian constitutional law and a passion for making complex legal concepts accessible to everyone, I specialize in creating comprehensive, research-based content that bridges the gap between academic law and practical understanding. Having worked extensively on fundamental rights provisions and landmark constitutional cases, I bring both scholarly depth and practical insight to legal content creation. When not researching constitutional provisions, I enjoy analyzing Supreme Court judgments and their impact on Indian democracy.

Follow for more insightful legal content and constitutional analysis.

Internal Link Suggestions:

- Article 14 of Indian Constitution (Right to Equality)

- Article 15 of Indian Constitution (Prohibition of Discrimination)

- Article 16 of Indian Constitution (Equality of Opportunity)

External Link Suggestions:

- Supreme Court of India official website (sci.gov.in)

- Constitution of India official text (legislative.gov.in)

- Balaji Raghavan judgment (Supreme Court database)