A caste census is a systematic exercise undertaken by the government to collect detailed data about the caste identities of the population. Unlike a general population census, which primarily records age, gender, and religion, a caste census specifically seeks to map the complex social stratification of Indian society by gathering information on various caste groups, including Other Backward Classes (OBCs), Scheduled Castes (SCs), and Scheduled Tribes (STs). This data is crucial for understanding the distribution of social and economic opportunities, as caste remains a powerful determinant of access, privilege, and exclusion in India.

The significance of a caste census lies in its potential to guide evidence-based policymaking and ensure social justice. Accurate caste data helps identify disadvantaged groups, enabling the government to design targeted welfare schemes, monitor the effectiveness of affirmative action policies, and ensure equitable distribution of resources. It also provides the empirical foundation needed to revise reservation quotas and address issues of representation in education, employment, and political institutions, in line with constitutional mandates such as Article 340 (which empowers the government to investigate the conditions of backward classes).

Table of Contents

Historically, India has not conducted a comprehensive caste census since 1931. Although the British colonial administration began enumerating castes in 1881, and the 1931 census remains the last full caste enumeration, post-independence governments discontinued this practice. From 1951 onwards, only SCs and STs have been officially counted in the decennial census, while OBCs and other groups have remained largely invisible in national statistics.

The rationale for this exclusion was to avoid deepening social divisions in a newly independent nation, but the unintended consequence has been a persistent data vacuum. This lack of updated caste data has complicated the implementation of reservation policies and hindered efforts to address social and caste inequalities.

In recent years, the demand for a caste census has gained momentum, with advocates arguing that comprehensive data is essential for accountability, inclusion, and the realization of constitutional ideals of equality and social justice. The legal framework for conducting a census, including caste enumeration, is provided by the Census Act, 1948, which empowers the government to collect such information without requiring specific amendments for caste data. As India debates the future of caste enumeration, the issue remains central to the country’s quest for a more inclusive and equitable society.

Legal Framework for Caste Census

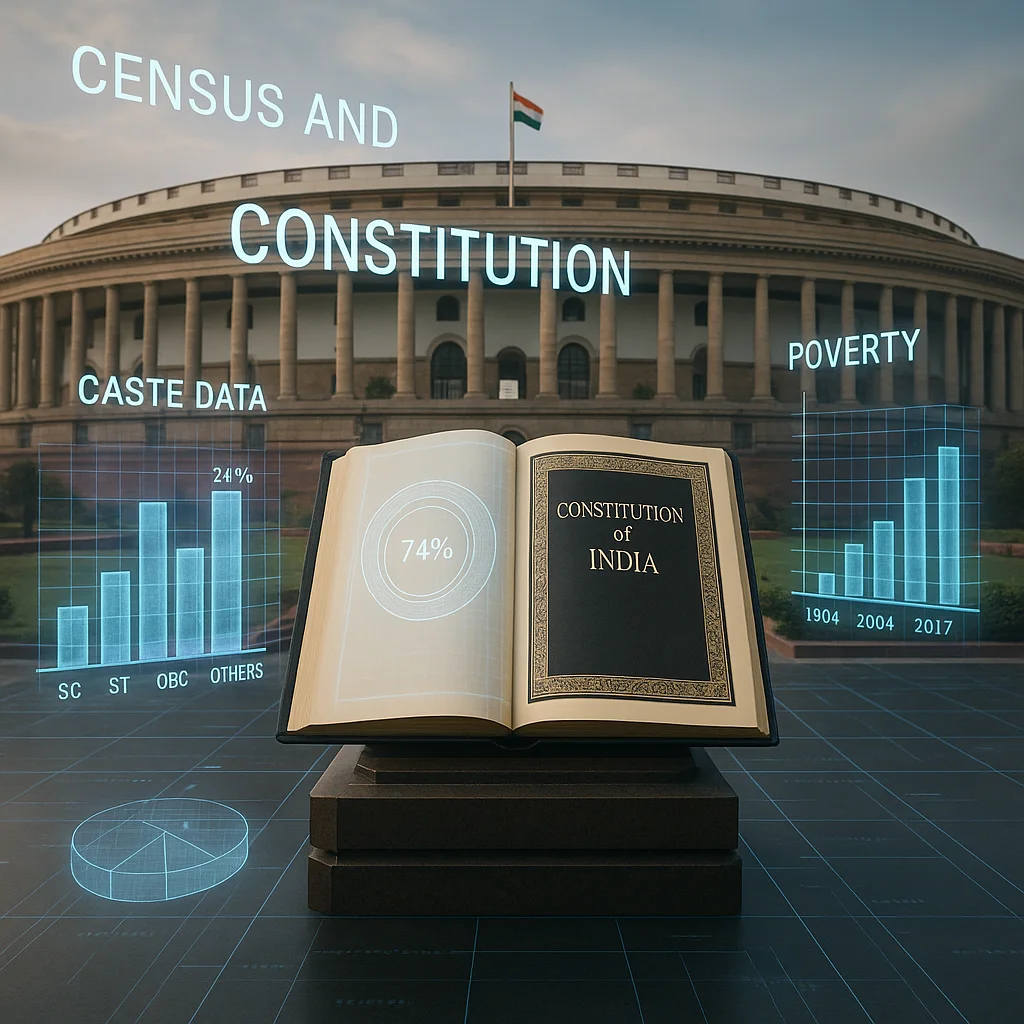

Statutory Basis: Census Act, 1948

The Census Act, 1948 provides the legal foundation for conducting censuses in India. Under Sections 3–8, the Registrar General and Census Commissioner (RG&CC) is empowered to design census schedules, appoint staff, and enforce compliance. For caste enumeration, Section 8 explicitly allows census officers to ask questions deemed necessary by the government, including those about caste identity. This statutory authority eliminates the need for amendments to include caste-related questions, as the Act grants flexibility to modify the census proforma through gazette notifications.

Confidentiality and Privacy Protections

Section 15 of the Census Act ensures strict confidentiality of census records. It prohibits the inspection of census data by anyone except authorized personnel and bars its use as evidence in civil or criminal proceedings. This provision safeguards individual privacy, encouraging truthful responses during data collection. For instance, caste-related information collected under the Act cannot be disclosed under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2005, due to this statutory immunity.

Precedent: Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) 2011

The SECC 2011 serves as a key precedent for caste enumeration, though it was conducted separately from the general census. Unlike the Census Act, the SECC operated under the administrative control of the Ministry of Rural Development and focused on linking caste data with socio-economic indicators. However, its findings were deemed “unusable” by the Supreme Court in 2021 due to inaccuracies and methodological flaws. Key lessons from the SECC include:

- Legal Limitations: Conducted without the binding force of the Census Act, SECC data lacked statutory protection and reliability.

- Data Challenges: Overlapping state and central OBC lists, manual errors, and incomplete coverage hindered its utility.

- Policy Impact: Despite flaws, SECC 2011 influenced welfare schemes like the National Food Security Act by integrating caste-economic data.

Recent Developments

In 2025, the Union Cabinet approved caste enumeration under the Census Act, 1948, ensuring a uniform framework for data collection. This marks a shift from the SECC’s ad hoc approach, leveraging digital tools and standardized codes for caste classification. The move aligns with judicial demands for empirical data to justify affirmative action, as emphasized in the Indra Sawhney case.

By anchoring caste enumeration in the Census Act, India aims to balance legal rigor with socio-political imperatives, addressing past shortcomings while upholding constitutional mandates for equality and privacy.

Constitutional Provisions and Institutional Mechanisms

Article 340: Investigating Backward Classes

Article 340 empowers the President to appoint commissions to investigate the conditions of socially and educationally backward classes (SEBCs) and recommend measures for their upliftment. This provision has been invoked twice:

- First Backward Classes Commission (1955): Headed by Kaka Kalelkar, it identified 2,399 backward castes but faced rejection due to vague criteria.

- Second Backward Classes Commission (1979): Led by B.P. Mandal, it recommended 27% reservation for OBCs in government jobs, which was partially implemented in 1990.

Article 338B: National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC)

The 102nd Constitutional Amendment Act (2018) established the NCBC as a constitutional body under Article 338B, granting it powers to:

- Advise on inclusion/exclusion of castes in the Central OBC list.

- Investigate grievances related to SEBC rights and safeguards.

- Function as a civil court during inquiries (e.g., summon witnesses, demand documents).

The NCBC’s recommendations, however, are not binding on the government, creating debates about its effectiveness.

State vs. Central OBC Lists: Policy Challenges

India’s federal structure has led to dual OBC lists:

- Central List: Includes ~2,650 castes recognized nationwide for central jobs and education.

- State Lists: Vary significantly, with states like Maharashtra (261 castes) and Odisha (200) having larger lists.

Key Issues:

- Exclusion from Central Benefits: Over 500 state-recognized OBC castes (e.g., in West Bengal, Bihar) lack access to central reservations.

- Creamy Layer Disparities: Income thresholds for excluding affluent OBCs differ between states and the Centre, causing confusion.

- Judicial Interventions: The Supreme Court, in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992), upheld 27% OBC quotas but emphasized the need for periodic revisions.

Recent Developments:

- The Rohini Commission (2017) is examining sub-categorization of OBCs to ensure equitable distribution of benefits.

- Proposals for a Unified Caste Code Directory aim to harmonize state and central lists, reducing administrative overlaps.

This dual-list system underscores the tension between federal autonomy and uniform social justice, requiring legal and policy reforms to bridge gaps.

Historical Background

Caste Data in Pre-Independence Censuses

The enumeration of caste in India began under British colonial rule, with systematic data collection starting in the late 19th century. The first comprehensive colonial census in 1871 included caste as a key category, aiming to help the British understand and administer the complex Indian society. Over the decades, the methodology evolved, with each census from 1872 to 1941 recording caste, tribe, and sometimes even sub-caste identities. By the 1901 census, there were 1,646 distinct castes recorded, which increased to over 4,000 by the 1931 census.

The 1931 census stands out as the last full enumeration of caste across India. This exercise revealed the immense diversity and fluidity of caste identities, as well as the challenges in classification. British officials noted that many groups would change their reported caste from one census to the next in pursuit of higher social status, and regional variations in caste roles and names were common. The census data was used for administrative purposes, including the allocation of quotas and separate electorates under the Government of India Act, 1935, but it also reinforced social hierarchies and sometimes fueled political mobilization around caste identity.

Despite methodological challenges-such as the lack of fixed caste definitions, regional inconsistencies, and the influence of local elites-the colonial censuses played a significant role in shaping how caste is understood in modern India. By 1931, caste data had become an important, if controversial, tool for both governance and social reform.

Post-Independence: Listing Only SCs and STs Since 1951

After independence in 1947, India’s leadership made a conscious decision to stop the comprehensive enumeration of caste in the national census. Starting with the 1951 census, only Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) were specifically counted, as mandated by the Constitution for the purpose of implementing affirmative action and reservation policies. This policy was rooted in the belief that continuing to count all castes would perpetuate divisions and hinder national unity.

The lists of SCs and STs are updated before each census, based on the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 and the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950, in accordance with Articles 341 and 342 of the Constitution. These lists are state and union territory-specific, and only those groups notified in the official lists are counted as SC or ST in the census.

While the census has continued to collect detailed data on SCs and STs for constitutional and policy requirements, it has not gathered comprehensive data on Other Backward Classes (OBCs) or other caste groups since 1951. This gap has led to ongoing debates and demands for a new caste census, especially as the need for accurate data to inform reservation policies and social justice measures has grown. The 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) attempted to address this gap, but its caste data was not fully published due to inconsistencies and classification challenges.

In summary, the historical trajectory of caste enumeration in India reflects both the administrative legacy of colonial rule and the post-independence commitment to social justice-while also highlighting the persistent complexities and controversies surrounding caste in Indian society.

Rationale and Need for Caste Census

Evidence-Based Policymaking and Targeted Welfare

A caste census provides the government with precise and up-to-date data on the socio-economic status of different caste groups, which is crucial for evidence-based policymaking. Without such data, policies risk being based on outdated assumptions or incomplete information, leading to inefficiencies and exclusion of deserving groups.

For example, the lack of accurate caste data has resulted in significant gaps in the implementation of welfare schemes, as seen in Bihar, where millions eligible for food subsidies were left out due to inaccurate beneficiary lists. Reliable caste data enables the government to allocate resources more effectively and design targeted welfare programs that address the real needs of marginalized communities.

Revising Reservation Quotas and Ensuring Constitutional Equality

The current reservation policies for education and government jobs are largely based on the 1931 caste census, making them potentially misaligned with present-day realities. A fresh caste census can provide a factual basis for reviewing and rationalizing reservation quotas, ensuring that they reflect the actual socio-economic status of various groups. This is essential for upholding Article 14 of the Constitution (right to equality) and Article 21 (right to life and dignity), as these provisions mandate that all citizens have equal access to opportunities and protection against discrimination.

Accurate data also helps monitor the impact of affirmative action and ensures that benefits reach those who are truly disadvantaged, while preventing misuse by relatively privileged sections within reserved categories.

Addressing Social Justice and Representation Gaps

Caste-based discrimination and social inequality remain deeply entrenched in Indian society, influencing access to education, employment, and political representation. A caste census is necessary to identify and uplift marginalized groups, thereby fulfilling the constitutional mandate of social justice under Article 340 (which provides for the appointment of commissions to investigate the conditions of backward classes). Comprehensive caste data can help bridge representation gaps in public institutions and ensure that policy interventions are inclusive and equitable. Moreover, by making the social structure visible, a caste census dispels myths and brings transparency to the debate on reservation and affirmative action.

In summary, a caste census is not just a statistical exercise but a constitutional and moral imperative for building a more just, inclusive, and equitable society. It enables the government to design policies grounded in reality, revise quotas to match contemporary needs, and address the historical injustices that continue to shape Indian society

Challenges and Concerns

Legal and Ethical Issues

The caste census faces significant legal and ethical hurdles, particularly regarding data privacy and misuse. Under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPPA), 2023, caste data is not classified as “sensitive personal data,” unlike categories like religion or biometrics. This omission weakens safeguards against misuse, such as caste-based profiling or exclusion from welfare schemes. While the Census Act, 1948 (Section 15) ensures confidentiality and prohibits using census data as evidence in courts, concerns persist about leaks or unauthorized access, especially given India’s history of caste-based discrimination.

Ethically, collecting caste data risks reinforcing social divisions. For example, during the SECC 2011, some households underreported assets to qualify for benefits, while others misreported caste to avoid stigma. The lack of explicit consent mechanisms under the DPPA further complicates ethical compliance, as individuals cannot opt out of sharing caste details in a mandatory census.

Administrative Challenges

Accurate data collection remains a major hurdle. The SECC 2011 highlighted flaws like manual entry errors, duplication (e.g., 46 lakh castes reported), and regional inconsistencies in caste names (e.g., “Yadav” vs. “Yadava”). Unlike the SECC, which allowed public objections, the Census Act bars data verification at the grassroots, raising concerns about reliability.

Logistical challenges include training 3 million enumerators to handle caste nuances and countering misinformation. For instance, during Telangana’s 2024 caste survey, rumours linked the exercise to the National Register of Citizens (NRC), deterring Muslim participation. Urban-rural divides and digital literacy gaps further complicate data collection, especially with the 2025 census relying on mobile apps for real-time updates.

Judicial Oversight

The Supreme Court has consistently emphasized evidence-based reservation policies. In Ashoka Kumar Thakur v. Union of India (2007), the Court upheld 27% OBC quotas but mandated exclusion of the “creamy layer” and periodic revision of caste lists using updated data. It criticized reliance on the 1931 census, calling it “obsolete” for modern policymaking.

However, judicial scrutiny poses risks. Courts may strike down reservation quotas if the caste census reveals discrepancies in OBC population estimates or fails to justify the 50% cap on total reservations (set in the Indra Sawhney case). For example, Maharashtra’s Maratha quota was invalidated in 2021 for exceeding this cap without empirical backing.

Balancing Risks and Reforms

While the caste census is legally viable under the Census Act, its success hinges on addressing privacy gaps in the DPPA, ensuring algorithmic transparency in data processing, and fostering public trust through awareness campaigns. Without these measures, the exercise risks deepening social fractures rather than bridging them.

Governance and Policy Implications

Re-Calibrating Reservation Policies

The 2025 caste census will provide empirical data to revise India’s reservation framework, which currently relies on outdated 1931 figures. For instance, Bihar’s 2023 caste survey revealed OBCs and EBCs constitute 63% of the population, prompting demands to breach the Supreme Court’s 50% reservation cap. The census data could justify sub-categorizing quotas to prioritize marginalized groups within OBCs, as recommended by the Rohini Commission (2023), which found 97% of central OBC benefits went to just 25% of castes. This aligns with the Supreme Court’s directive in Ashoka Kumar Thakur v. Union of India (2007) to base reservations on “contemporaneous data”.

Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) and Caste-Economic Overlays

Integrating caste data with DBT can enhance targeted welfare delivery. For example, the SECC 2011 linked caste identities with socio-economic status to identify 8.5 crore households for subsidized food under the National Food Security Act. The 2025 census’s caste-economic overlays will enable:

- Precision targeting: Excluding affluent groups (e.g., dominant OBCs) from subsidies.

- Reduced leakage: Aadhaar-linked DBT has already saved ₹3.48 lakh crore by eliminating ghost beneficiaries.

- Dynamic adjustments: Allocating funds based on real-time caste-wise deprivation metrics, as seen in PM-KISAN’s ₹22,106 crore savings via ineligible beneficiary removal.

Sub-Categorization Within OBCs

The Rohini Commission proposed splitting the 27% OBC quota into four sub-groups (2%, 6%, 9%, 10%) to prioritize underrepresented communities like Khatiks and Nai castes. States like Karnataka (70% OBC population) and Bihar have already implemented sub-categories, reserving 18% for EBCs. The Supreme Court’s 2024 verdict allowing SC/ST sub-classification underscores the need for “quantifiable data”-a gap the 2025 census will fill.

Key Reforms Enabled by Caste Data:

| Policy Area | Current Challenge | Post-Census Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Reservation quotas | Reliance on 1931 data | Dynamic quotas based on 2025 data |

| DBT targeting | Uniform subsidies for all OBCs | Graded benefits by caste-income |

| Creamy layer exclusion | Fixed ₹8 lakh income threshold | Variable thresholds per sub-caste |

Balancing Constitutional Mandates

While Article 16(4) permits reservations for “backward classes,” the 50% cap (Indra Sawhney case) faces pressure from data showing OBC populations exceeding 60% in states. The census will test whether “exceptional circumstances” (per SC rulings) exist to justify breaching the cap, balancing Articles 14–16 (equality) with Article 46 (promoting weaker sections).

In summary, the caste census is a governance tool to align India’s legal and welfare architecture with ground realities, ensuring reservations and DBT evolve from rigid entitlements to dynamic, equity-driven instruments.

The Way Forward

Unified Caste Code Directory (UCCD): Standardizing Classification

A Unified Caste Code Directory (UCCD) is critical to harmonize India’s fragmented caste lists. Currently, over 5,000 caste names exist across central and state OBC lists (e.g., “Yadav” in Uttar Pradesh vs. “Yadava” in Maharashtra), leading to administrative chaos. The UCCD would:

- Merge central and state lists into a single digital repository with unique 6-digit codes for each caste.

- Eliminate redundancies: For example, Bihar’s 2023 survey found 214 castes repeated across state and central lists.

- Enable interoperability: Allow state welfare schemes to seamlessly integrate with central databases, as piloted in Karnataka’s E-Shakti project.

Implementation Steps:

- Collaborative Framework: The National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC) and State Backward Classes Commissions will jointly validate caste entries.

- Machine Learning for De-duplication: Algorithms like T3S (Two-Stage Sampling Selection) can merge variations (e.g., “Lohar” and “Luhar”) by phonetic similarity and regional context.

- Public Feedback Portal: Allow citizens to verify/correct caste names via a vernacular app, as tested in Telangana’s 2024 caste survey.

Periodic Updates and Algorithmic Governance

Caste dynamics evolve, necessitating decadal updates synchronized with the Census. The UCCD must integrate:

- Dynamic Inclusion Mechanism: Automatically add newly recognized castes (e.g., Hindu Jat in Rajasthan, 2025) after NCBC scrutiny.

- AI-Driven Anomaly Detection: Flag improbable demographic shifts (e.g., a 300% spike in a caste’s population) for manual review, as done in Bihar’s 2023 survey.

- Sunset Clauses: Remove castes that no longer meet backwardness criteria, subject to judicial review (Indra Sawhney v. Union of India).

Ethical Machine Learning and Data Justice

While AI can streamline caste data processing, it risks amplifying biases. For example, ChatGPT erroneously changed “Singha” (Dalit surname) to “Sharma” (upper-caste) due to training on caste-skewed academic datasets. Mitigation strategies include:

- Caste-Conscious Algorithms: Retrain models using inclusive datasets (e.g., SECC 2011 socio-economic parameters) to avoid privileging dominant castes.

- Transparency Audits: Publish algorithmic decision-making criteria under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP), 2023.

- Community Oversight: Involve marginalized groups in UCCD design, as mandated by Article 338B (NCBC’s advisory role).

Legal and Institutional Reforms

- Parliamentary Oversight Committee: A bipartisan body to approve UCCD updates and prevent politicization, modeled after the Standing Committee on Social Justice.

- Caste Data Protection: Classify caste data as “sensitive” under DPDP Act rules to prevent misuse (e.g., profiling by private employers).

- Judicial Capacity Building: Train judges on caste census methodologies to adjudicate reservation disputes, as recommended by the Law Commission (2024).

By combining technical rigor with constitutional safeguards, India can transform caste data into a tool for equity-not division.

Conclusion

India’s caste census represents a pivotal effort to reconcile constitutional commitments to equality (Article 14) and social justice (Article 340) with the ethical imperatives of data governance. While the census has the potential to address historical inequities by enabling targeted welfare and evidence-based reservations, its success hinges on balancing transparency with privacy and preventing the reinforcement of caste divisions.

Legal safeguards, such as the Census Act, 1948 (Section 15)-which ensures data confidentiality-and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP), 2023, must be strengthened to classify caste data as “sensitive” and shield marginalized groups from misuse. Judicial precedents like Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992) underscore the need for empirical data to justify reservations while adhering to the 50% cap, ensuring compliance with constitutional equality.

Institutional reforms, including the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC) and proposed Unified Caste Code Directory (UCCD), are critical to harmonizing fragmented caste lists and eliminating administrative redundancies. Lessons from flawed exercises like the SECC 2011 highlight the importance of algorithmic de-duplication and community participation in data collection.

Ultimately, the caste census must transcend political expediency to become a tool for transformative governance. By anchoring it in legal rigor, ethical data practices, and inclusive policymaking, India can harness caste data to dismantle systemic barriers-not deepen them-and advance toward the constitutional vision of a truly equitable society.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on the Caste Census

Q1. What is the caste census in India?

The caste census is an official process of collecting detailed data on the caste identities of all individuals in India, alongside other demographic information. Its aim is to inform policies on welfare, reservations, and inclusive development by providing an updated picture of the country’s social structure.

Q2. When was the last full caste census conducted?

The last comprehensive caste census was held in 1931. After Independence, only Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) were counted in the regular census, with Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and other groups excluded from official enumeration.

Q3. What is the legal basis for the caste census?

The caste census is governed by the Census Act, 1948. The Act empowers the Registrar General and Census Commissioner to design census schedules and include questions on caste without needing an amendment to the law. Census is a Union subject under Entry 69, Union List, Seventh Schedule of the Constitution.

Q4. Why is the caste census important now?

Accurate caste data is essential for evidence-based policymaking, targeted welfare, and revising reservation quotas. Current reservation policies are based on outdated or estimated data, and the caste census will enable a reassessment of quotas and more equitable distribution of benefits.

Q5. How will the caste census be conducted?

For the first time, the census will be digital, using a mobile app and a standardized drop-down caste code directory to avoid data duplication. The Central and State OBC, SC, and ST lists will be merged to create a comprehensive codebook, with pre-testing to ensure smooth implementation.

Q6. Which list of OBCs will be used for enumeration?

A unified directory will be created by merging the Central OBC list (about 2,650 communities) with State OBC lists. This aims to minimize overlaps and classification ambiguities, though differences between state and central lists remain a challenge.

Q7. What are the main challenges in implementing the caste census?

Key challenges include:

- Creating a standardized caste code directory due to regional and linguistic variations

- Managing discrepancies between state and central OBC lists

- Addressing political sensitivities and potential disputes over classification

- Ensuring data accuracy and public trust in the process.

Q8. How will privacy and data protection be ensured?

The Census Act, 1948 (Section 15) guarantees confidentiality of census data, prohibiting its use as evidence in court and restricting access to authorized personnel only. However, concerns remain about data privacy, especially as caste data is not currently classified as “sensitive” under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023.

Q9. Can the caste census impact reservation policies?

Yes. Updated data may prompt demands to revise reservation quotas, potentially challenging the Supreme Court’s 50% cap on total reservations. States like Karnataka and Bihar have already used recent caste surveys to advocate for higher quotas for OBCs.

Q10. What happens if someone provides false information?

Providing false information in the census is an offence under the Census Act, 1948, and is punishable as per its provisions. The Act prevails over general laws like the Indian Penal Code in such matters, as clarified by the Supreme Court to prevent double jeopardy.

Q11. How will the caste census findings be used?

The data will support targeted policymaking, accurate delimitation of constituencies, implementation of women’s and caste-based reservations, and more inclusive governance. It will also help academic research and evidence-based interventions in social justice.

Q12. Have any states already conducted caste surveys?

Yes, states like Bihar, Telangana, and Karnataka have recently completed their own caste-based surveys, influencing the national debate and policy direction.

These FAQs address the most common legal and policy questions about the caste census, reflecting its significance, legal safeguards, and the challenges ahead for Indian governance.

- Address common legal and policy queries related to the caste census

This blog offers a clear, concise overview of the caste census, enriched with well-structured FAQs. It’s very informative and easy to understand. Great for beginners and curious readers alike.

[…] nationwide caste census is seen as a crucial step to understand how caste inequalities are still continuing in India and to […]