The Indian Constitution is celebrated for its robust protection of individual rights, but at its heart lies a unique synergy: the golden triangle of Indian Constitution. This powerful concept, woven through Articles 14, 19, and 21, forms the unshakeable foundation upon which Indian democracy rests. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore what the golden triangle of Indian Constitution means, why it’s so vital, how it has evolved through landmark judgments, and why it remains the gold standard for justice, liberty, and equality in India.

Table of Contents

What is the Golden Triangle of Indian Constitution?

The golden triangle of Indian Constitution refers to the harmonious interplay between three fundamental rights:

- Article 14: Right to Equality – Guarantees equality before the law and equal protection of the laws, prohibiting discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth.

- Article 19: Right to Freedom – Provides citizens with essential freedoms, including speech and expression, assembly, association, movement, residence, and profession, subject to reasonable restrictions.

- Article 21: Right to Life and Personal Liberty – Ensures that no person is deprived of life or personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law.

Together, these articles are called the golden triangle of Indian Constitution because of their interconnectedness and their role as the bedrock of individual liberty and justice in India.

Historical and Doctrinal Context of the Golden Triangle

After India’s independence, the Constituent Assembly faced the monumental task of crafting a Constitution that would enshrine democracy, justice, and equality for all citizens. The framers, drawing from the painful experiences of colonial rule and partition, were determined to establish a legal framework that would protect individual freedoms and prevent the abuse of state power.

Intent of the Framers:

Articles 14 (Right to Equality), 19 (Right to Freedom), and 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty) were deliberately included to serve as the foundation of individual rights in the new Republic. These provisions reflected the framers’ vision of a society where liberty, equality, and justice would not be mere ideals, but enforceable rights.

Doctrinal Evolution:

- Early Years (1950s–1970s): The judiciary initially interpreted these rights in isolation. In A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras, the Supreme Court held that each right was distinct and could be applied separately.

- Shift in Judicial Philosophy: Over time, landmark cases like Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala and especially Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India transformed this approach. The Court recognized that these rights are interdependent and must be read together to provide comprehensive protection against arbitrary state action.

- The Golden Triangle Doctrine: The “Golden Triangle” analogy emerged to describe how Articles 14, 19, and 21 collectively form the backbone of India’s constitutional democracy, ensuring that laws affecting personal liberty are fair, just, and reasonable, and uphold both equality and freedom.

This doctrinal evolution has ensured that the Constitution remains a living document, capable of adapting to new challenges while safeguarding the core values of justice, liberty, and equality.

Why Are Articles 14, 19, and 21 Called the Golden Triangle of Indian Constitution?

The term “golden triangle” is not just a metaphor. In geometry, a triangle is the strongest shape, and similarly, these three articles form the strongest legal framework for protecting individual rights. The golden triangle of Indian Constitution ensures that:

- Equality (Article 14), Freedom (Article 19), and Life and Liberty (Article 21) are not isolated guarantees but reinforce and support each other.

- Any law or state action affecting personal liberty must pass the tests of all three articles: it must be fair (Article 21), non-discriminatory (Article 14), and not infringe on freedoms (Article 19).

- This synergy prevents arbitrary or unjust actions by the State, making the golden triangle of Indian Constitution a shield for every citizen.

The Three Pillars of the Golden Triangle

Article 14: Right to Equality

Article 14 is the cornerstone of the golden triangle of Indian Constitution. It mandates that the State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or equal protection of the laws within the territory of India. This article:

- Prohibits discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth.

- Ensures that laws apply equally to all, and any classification must be reasonable and not arbitrary.

- Has been used to strike down discriminatory practices and laws, reinforcing the principle of equal justice.

Article 19: Right to Freedom

Article 19 is the second pillar of the golden triangle of Indian Constitution. It grants six fundamental freedoms to citizens:

- Freedom of speech and expression

- Freedom to assemble peacefully

- Freedom to form associations or unions

- Freedom to move freely throughout India

- Freedom to reside and settle anywhere in India

- Freedom to practice any profession or trade

These freedoms are not absolute; they can be reasonably restricted to maintain public order, security, and morality.

- Reasonable Restrictions: These freedoms are subject to reasonable restrictions in the interest of:

- Sovereignty and integrity of India

- Security of the State

- Friendly relations with foreign States

- Public order, decency, or morality

Article 19 ensures that Indian democracy is vibrant, participatory, and open to dissent.

Article 21: Right to Life and Personal Liberty

Article 21 is the most expansive pillar of the golden triangle of Indian Constitution. It states: “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law”.

- The Supreme Court has interpreted “life” to mean more than mere animal existence; it includes the right to live with dignity, privacy, and a clean environment.

- Article 21 acts as a safeguard against arbitrary state action and has been the basis for recognizing new rights such as the right to education, health, and shelter.

The Interplay: How the Golden Triangle of Indian Constitution Works

The genius of the golden triangle of Indian Constitution lies in its interplay. The Supreme Court, especially in the landmark case of Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978), held that these articles must be read together. Any law depriving a person of personal liberty must:

- Be just, fair, and reasonable (Article 21).

- Not be arbitrary or discriminatory (Article 14).

- Not unreasonably restrict freedoms (Article 19).

This approach ensures that the State cannot bypass one right by claiming compliance with another. The golden triangle of Indian Constitution thus acts as a comprehensive shield for citizens.

Practical Implications of the Golden Triangle

The doctrine of the Golden Triangle—comprising Articles 14, 19, and 21—has far-reaching effects on the lives of Indian citizens and the functioning of the legal system:

- Protection from Arbitrary Actions:

Any government action that affects an individual’s liberty, freedom, or equality must be “just, fair, and reasonable.” This ensures that citizens are shielded from arbitrary or oppressive laws and executive actions. - Empowerment of Citizens:

These articles provide a robust framework for individuals to challenge violations of their fundamental rights in court. For example, if a law restricts freedom of speech, it must also meet the standards of equality and due process. - Influence on Legislation:

Lawmakers must ensure that new laws comply with the triple test: they must not be arbitrary (Article 14), must not unduly restrict freedoms (Article 19), and must respect life and personal liberty (Article 21). This shapes how laws are drafted and interpreted. - Social Impact:

Article 14 has played a crucial role in eradicating discriminatory practices and promoting social justice. Article 19 encourages a culture of open dialogue and association, while Article 21 safeguards personal dignity and security. - Judicial Review:

The judiciary uses the Golden Triangle as a standard for reviewing the constitutionality of laws and executive actions, ensuring ongoing protection of fundamental rights.

Example:

After the Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India judgment, the government cannot simply restrict a person’s passport without providing a fair process and justification. This protects not just the right to travel, but also the broader rights to equality and personal liberty.

Comparative and Analytical Insights: The Golden Triangle Doctrine

Evolution of Interpretation:

- Pre-Maneka Gandhi Era:

Fundamental rights were viewed as separate “compartments.” For example, in A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras, the Supreme Court held that each right (equality, freedom, personal liberty) was to be interpreted in isolation. - Post-Maneka Gandhi Era:

The Supreme Court, in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, recognized that Articles 14, 19, and 21 are interdependent. Any law affecting personal liberty must satisfy the requirements of all three articles—ensuring it is fair, reasonable, and non-arbitrary.

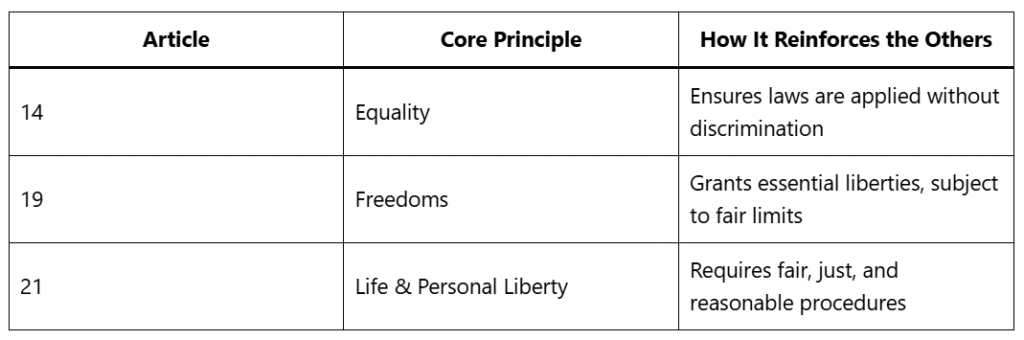

Interdependence of Articles (Analytical Table):

Broader Impact:

This integrated approach reflects the Constitution’s holistic vision and has influenced the development of other rights and judicial doctrines in India.

The “golden triangle” doctrine has become a cornerstone of Indian constitutional law, ensuring that state action is rigorously scrutinized and that citizens’ rights are robustly protected.

Landmark Judgments Shaping the Golden Triangle of Indian Constitution

A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras (1950)

Initially, the Supreme Court interpreted each right separately. Article 21 was seen as procedural, and laws depriving liberty were upheld if they followed “procedure established by law,” even if unfair.

Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978)

This case revolutionized the understanding of the golden triangle of Indian Constitution. The Court held that Articles 14, 19, and 21 are interconnected, and any law affecting liberty must be fair, just, and reasonable, passing the tests of all three articles.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India AIR 1978 SC 597 is pivotal in the evolution of the Golden Triangle doctrine. In this case, the Court was asked to decide whether the government’s order to impound Maneka Gandhi’s passport, without providing reasons, violated her fundamental rights.

Key Takeaways from the Judgment:

- The Court held that “personal liberty” in Article 21 should be interpreted broadly, encompassing a range of rights beyond mere freedom from physical restraint.

- It established that any law depriving a person of liberty must be “just, fair, and reasonable,” not arbitrary or oppressive.

- Most importantly, the Court ruled that Articles 14 (equality), 19 (freedoms), and 21 (personal liberty) are not isolated provisions but must be read together. Any law affecting personal liberty must meet the standards of all three articles.

- This marked a shift from the earlier position in A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras, where the articles were treated as separate compartments.

Impact:

- The “Golden Triangle” ensures that state action affecting fundamental rights is subject to rigorous judicial scrutiny, protecting citizens from arbitrary state power.

Minerva Mills v. Union of India (1980)

The Supreme Court reaffirmed that the golden triangle of Indian Constitution is part of the “basic structure” of the Constitution, which cannot be amended or destroyed.

R.C. Cooper v. Union of India (1970):

The Court shifted towards reading fundamental rights collectively, emphasizing that State action must withstand scrutiny under multiple articles simultaneously.

Other Notable Cases

- Francis Coralie v. Union Territory of Delhi: Expanded Article 21 to include the right to live with human dignity.

- Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation: Recognized the right to livelihood under Article 21.

Golden Triangle of Indian Constitution in Everyday Life

The golden triangle of Indian Constitution is not just a legal doctrine; it impacts every Indian’s daily life:

- Equality: Protects against discrimination in jobs, education, and public spaces.

- Freedom: Ensures the right to speak, protest, and associate freely.

- Life and Liberty: Safeguards privacy, dignity, and personal choices, from marriage to travel.

Recent developments, such as the recognition of the right to privacy as a fundamental right, show the living and evolving nature of the golden triangle of Indian Constitution.

Comparative Perspective: The Golden Triangle and Global Constitutionalism

While many constitutions guarantee rights, the golden triangle of Indian Constitution stands out for its integrated approach. Unlike the U.S. Bill of Rights, where rights are often interpreted in isolation, Indian courts ensure that equality, freedom, and liberty are mutually reinforcing. This holistic method is a model for constitutional democracies worldwide.

Criticisms and Challenges

No doctrine is without challenges. Critics argue that:

- The golden triangle of Indian Constitution sometimes faces enforcement gaps, especially for marginalized groups.

- Balancing individual rights with collective interests (security, public order) can be contentious.

- Judicial activism in expanding Article 21 is sometimes seen as overreach.

However, these debates highlight the vitality and relevance of the golden triangle of Indian Constitution in India’s evolving democracy.

Frequently Asked Questions

u003cstrongu003eQ1: What is the Golden Triangle of the Indian Constitution?u003c/strongu003e

The Golden Triangle refers to Articles 14 (Right to Equality), 19 (Right to Freedom), and 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty). These articles are foundational to protecting citizens’ fundamental rights and are closely interlinked.

u003cstrongu003eQ2: Why are these articles called the “Golden Triangle”?u003c/strongu003e

They are termed “golden” because of their supreme importance in safeguarding liberty, equality, and justice. The “triangle” refers to their interconnectedness—they must be read and enforced together to ensure robust protection from arbitrary state action.

u003cstrongu003eQ3: How did the Supreme Court establish the doctrine?u003c/strongu003e

In the landmark case of u003cemu003eManeka Gandhi v. Union of Indiau003c/emu003e, the Supreme Court ruled that any law affecting personal liberty must satisfy the requirements of all three articles, not just one.

u003cstrongu003eQ4: What practical impact does this doctrine have?u003c/strongu003e

It means that any law or action by the government affecting your liberty or rights must be fair, just, and reasonable, and must not violate equality or the freedoms guaranteed under Article 19.

u003cstrongu003eQ5: Where can I learn more about each article?u003c/strongu003e

See our detailed guides on [Right to Equality], [Right to Freedom], and [Right to Life and Personal Liberty] for deeper insights.

u003cstrongu003eQ6: Is the right to property part of the golden triangle of Indian Constitution?u003c/strongu003e

No, the right to property was removed from the list of fundamental rights in 1978. The golden triangle specifically refers to Articles 14, 19, and 21.

Q7: u003cstrongu003eCan these rights be suspended?u003c/strongu003e

During a national emergency, certain rights under Article 19 can be suspended, but Articles 14 and 21 remain in force, underscoring the strength of the u003cstrongu003egolden triangle of Indian Constitutionu003c/strongu003e.

u003cstrongu003eQ8: How does the golden triangle protect digital rights?u003c/strongu003e

Recent judgments have interpreted Article 21 to include the right to privacy, protecting citizens in the digital age.

The Enduring Legacy of the Golden Triangle of Indian Constitution

The golden triangle of Indian Constitution—Articles 14, 19, and 21—forms the gold standard for justice, liberty, and equality in India. It ensures that every citizen is protected from arbitrary state action, enjoys essential freedoms, and lives with dignity. Through landmark judgments and evolving interpretations, the golden triangle of Indian Constitution remains the guardian of democracy and the promise of a just, fair, and inclusive society.

As India continues to grow and change, the golden triangle of Indian Constitution will remain the guiding light for all who seek justice, liberty, and equality. Every citizen should know, cherish, and assert these rights—because the golden triangle of Indian Constitution is not just a legal doctrine; it is the heartbeat of Indian democracy.