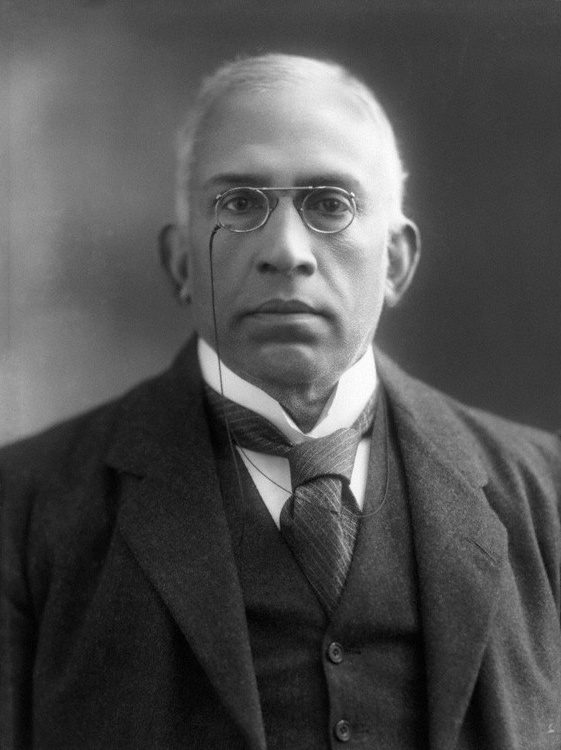

In the story of India’s freedom struggle, certain luminaries shine brighter upon closer inspection, revealing depths of courage and conviction that continue to inspire generations. Sir C Sankaran Nair (shankaran nair) stands tall among such figures—a legal colossus whose principled stand against British colonial injustice deserves far greater recognition than history has afforded him.

The recent release of Akshay Kumar’s powerful portrayal in “Kesari Chapter 2: The Untold Story of Jallianwala Bagh” (April 2025) has reignited interest in this remarkable statesman. Kumar’s nuanced performance captures the essence of Nair’s unwavering moral courage, particularly during his historic legal battle against Michael O’Dwyer in London’s King’s Bench—a David versus Goliath confrontation that exposed the deep-seated prejudices of the British Empire.

As the only Malayali to ever hold the prestigious position of Congress President and one of the youngest to do so, Nair’s contributions span the legal, political, and social reform landscapes of pre-independent India. Yet, it was his fearless challenge to the Crown following the Jallianwala Bagh massacre that truly cemented his legacy as a nationalist hero who valued truth and justice above personal safety or reputation.

This blog explores the extraordinary life and contributions of Sir C Sankaran Nair—a man who dared to hold the mighty British Empire accountable in its own courts and whose story reminds us that sometimes, moral victories transcend legal defeats in the pursuit of justice.

Table of Contents

Early Life and Education shankaran nair

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair was born on July 11, 1857, in Mankara village in Malabar’s Palakkad district (present-day Kerala) to an aristocratic family with historical prominence. Born into the matrilineal Chettur family, he was the son of Parvathy Amma Chettur and Mammayil Ramunni Panicker of the Mammayil family. Interestingly, Sankaran Nair received his family name “Chettur” through matrilineal succession, following the traditional Nair customs of Kerala.

His father worked as a Tahsildar under the British government, providing young Sankaran with early exposure to colonial administration. This background would later influence his nuanced understanding of the British system—appreciating its merits while boldly challenging its injustices.

Sankaran Nair’s educational journey began in the traditional style at home, as was customary for children from prominent families during that era. He continued his early schooling in various institutions across Malabar until he distinguished himself by passing the arts examination with first class honors from the Provincial School at Calicut (now Kozhikode).

His academic excellence earned him admission to the prestigious Presidency College in Madras (now Chennai), where he completed his arts degree in 1877. Demonstrating his intellectual prowess, he then pursued legal education at the Madras Law College, securing his law degree in 1879.

What set Nair apart early in his career was his fortunate association with Sir Horatio Shepherd, who would later become the Chief Justice of the Madras High Court. This mentorship under such a distinguished legal mind provided Nair with invaluable insights into the British legal system and helped shape his approach to jurisprudence.

This combination of traditional upbringing, formal Western education, and mentorship under a prominent British jurist equipped Sankaran Nair with a unique perspective that would later define his remarkable career. His educational background prepared him not just for professional success, but also instilled in him the courage and conviction to challenge injustice, even when it meant confronting the mighty British Empire on its own terms.

Professional Legal Career

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair’s professional journey stands as a testament to his exceptional legal acumen and unwavering principles. His career trajectory was remarkable not only for the prestigious positions he held but also for the progressive stance he maintained throughout his professional life.

Nair began his legal practice in 1880 at the Madras High Court, where his sharp intellect and oratorical skills quickly distinguished him among his peers. His reputation as a formidable legal mind grew steadily, earning him recognition from both Indian and British officials. By 1884, the Madras Government acknowledged his expertise by appointing him as a member of the committee tasked with inquiring into the state of Malabar, his home district.

His career reached significant milestones in quick succession:

- In 1899, he was appointed as Public Prosecutor, a position that showcased his prosecutorial skills

- By 1906, he rose to become the Advocate-General of Madras, succeeding C.A. White

- In 1908, he achieved the remarkable distinction of being appointed as a permanent Judge in the Madras High Court, a position he held until 1915

As a judge, Nair participated in several high-profile cases, including the special bench that tried the Collector Ashe murder case alongside Chief Justice C.A. White and William Ayling. His judicial temperament was characterized by fairness, independence, and a reformist outlook that often challenged the status quo.

Edwin Montague, the Secretary of State for India, once described Nair as an “impossible person” who “shouts at the top of his voice and refuses to listen to anything when one argues, and is absolutely uncompromising.” This description, though intended as criticism, actually highlights Nair’s unwavering commitment to his principles—a quality that earned him both admiration and opposition throughout his career.

His professional reputation continued to grow, leading to his appointment as Secretary to the Raleigh University Commission by Viceroy Lord Curzon in 1902. His contributions were recognized with the title ‘Commander of the Indian Empire’ in 1904, followed by knighthood in 1912—honors that acknowledged his service while never compromising his nationalist principles.

The pinnacle of his administrative career came in 1915 when he was appointed to the Viceroy’s Executive Council with charge of the Education portfolio. In this capacity, he wrote two famous Minutes of Dissent in the Despatches on Indian Constitutional Reforms in 1919, boldly pointing out the defects of British rule and suggesting reforms—an extraordinary act of courage for an Indian official in those times. Remarkably, the British government accepted most of his recommendations, demonstrating the weight his opinions carried even within the colonial administration.

Throughout his professional career, Nair maintained his position as a leader of the Madras bar, standing alongside other legal luminaries like C.R. Pattabhirama Iyer, M.O. Parthasarathy Iyengar, V. Krishnaswamy Iyer, and Sir V.C. Desikachariar. His professional achievements established him as one of the most distinguished Indian jurists of his era, whose legacy continues to inspire the legal fraternity to this day.

Landmark Legal Contributions

Sir C Sankaran Nair’s enduring legacy in Indian jurisprudence extends far beyond the positions he held. His contributions to the legal field were revolutionary, often challenging entrenched social prejudices and colonial biases through the power of legal reasoning and judicial courage.

As a judge of the Madras High Court from 1908 to 1915, Nair delivered several progressive judgments that were ahead of their time. His most celebrated ruling came in the landmark case of Budasna v Fatima (1914), where he upheld conversion to Hinduism and established that converts could not be treated as outcasts. This judgment was revolutionary in a society rigidly structured by caste and religious boundaries, effectively using the legal system to promote religious freedom and social equality.

Nair consistently championed social reform through his judicial pronouncements. He issued multiple judgments supporting inter-caste and inter-religious marriages at a time when such unions faced severe societal opposition. These rulings not only provided relief to individual petitioners but also gradually helped reshape societal attitudes toward marriage and personal choice.

His contributions to legal literature were equally significant. Recognizing the need for robust legal discourse in colonial India, Nair founded and edited two influential publications:

- The Madras Law Journal, which he established as an authoritative legal resource that continues to be cited in courtrooms across India even today

- The Madras Review, which provided a platform for intellectual discourse on legal and social issues, fostering critical thinking among the Indian legal community

Through these publications, Nair significantly contributed to the development of Indian jurisprudence during a critical period when the nation was beginning to articulate its own legal identity distinct from colonial impositions.

His legal philosophy was characterized by a unique blend of respect for established legal principles and a willingness to adapt them to serve justice and social progress. This approach is evident in his constitutional reform advocacy, where he authored two influential Minutes of Dissent in the Despatches on Indian Constitutional Reforms. These documents highlighted defects in British rule and suggested reforms, many of which were accepted by the British government—a testament to the persuasive power of his legal reasoning.

Perhaps most significantly, Nair demonstrated that the law could be a powerful tool for challenging injustice, even against the colonial masters themselves. His legal battle against Michael O’Dwyer regarding the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, though unsuccessful in the narrow sense of the verdict, established an important precedent: that colonial officials could be held accountable for their actions through legal means.

Sir C Sankaran Nair’s legal contributions exemplify how a principled jurist can use the law not merely to maintain order but to advance justice and social reform. His legacy continues to inspire generations of Indian lawyers and judges who value independence, reform, and the courage to stand up against injustice, regardless of the consequences.

Sir C Sankaran Nair Leadership in Indian National Congress

Sir Sankaran Nair’s association with the Indian National Congress represents one of the most significant yet underappreciated chapters in the organization’s early history. His leadership came during a formative period when the Congress was evolving from a modest gathering of educated Indians into a formidable political force.

In 1897, at the age of 40, Nair achieved a remarkable milestone when he was elected President of the Indian National Congress at its Amraoti (now Amravati) session. This achievement was particularly notable for several reasons:

- He became one of the youngest presidents in the Congress’s history

- He remains the only Malayali to have ever held this prestigious position

- His presidency came during a crucial transitional period for the national movement

His presidential address at the Amraoti session was a masterpiece of political vision and strategic thinking. Rather than resorting to fiery rhetoric, Nair delivered a measured yet powerful speech that outlined a clear path forward for India’s political future. He explicitly called for self-government with Dominion Status, demonstrating remarkable foresight at a time when many Congress leaders were still focused on more modest reforms.

“It is high time,” he declared in his address, “that we should secure for ourselves in India all the rights which British subjects enjoy in England.” This statement encapsulated his constitutionalist approach—demanding equality and self-determination while working within existing frameworks.

Before his national presidency, Nair had already established himself as a regional leader within the Congress. When the First Provincial Conference met in Madras in 1897, he was invited to preside over it, demonstrating his standing within the organization. His leadership style emphasized pragmatic reform over revolutionary rhetoric, believing that sustainable change required strategic engagement with existing institutions.

Nair’s relationship with the Congress evolved over time. His government positions from 1908 to 1921 temporarily interrupted his activities as a free political worker, creating a complex dynamic between his official responsibilities and his nationalist convictions. Later, he found himself at odds with certain aspects of Gandhi’s approach, particularly the Civil Disobedience movement, as he remained committed to constitutional agitation.

The internal conflicts between Moderates and Extremists within the Congress also caused him considerable disillusionment. Nevertheless, he maintained his advocacy for Indian self-governance, believing that Dominion Status should be the first stage, with complete independence achievable in the second stage—a position that reflected his pragmatic approach to political change.

Despite his significant contributions, contemporary political narratives have sometimes sidelined Nair’s legacy within the Congress in favor of other leaders. However, his presidency and principled stance on Indian self-governance remain an important chapter in the early history of the Indian National Congress—one that demonstrates the diversity of thought and approach that characterized India’s freedom struggle.

Nair’s leadership in the Congress embodied a vision of nationalism that valued reasoned dissent and strategic resistance over revolutionary upheaval—a perspective that continues to offer valuable insights for political leadership today.

Government Service and Honors

Sir Sankaran Nair’s government service presents a fascinating study in navigating the complex terrain between serving within a colonial administration while maintaining unwavering nationalist principles. His career in government service was marked by significant achievements, strategic influence, and ultimately, a principled resignation that shook the British establishment.

Nair’s entry into high-level government service began in 1902 when Viceroy Lord Curzon appointed him as a member of the prestigious Raleigh University Commission. This appointment recognized his educational expertise and provided him an early platform to advocate for educational reforms in India. His contributions to the Commission’s work earned him the title ‘Companion of the Indian Empire’ in 1904, an honor that acknowledged his growing stature in colonial administration.

His exceptional service and legal acumen were further recognized when he was knighted in 1912. While accepting such honors from the British Crown might seem contradictory for a nationalist, Nair viewed these positions pragmatically—as opportunities to influence policy from within and advocate for Indian interests at the highest levels of colonial government.

The pinnacle of his government service came in 1915 when he was appointed to the Viceroy’s Executive Council with charge of the Education portfolio. This made him one of the most powerful Indian officials in the colonial administration. As Education Member, he implemented several progressive reforms:

- Advocated for increased Indian control over educational institutions

- Pushed for greater allocation of resources to primary education

- Supported the expansion of technical and professional education for Indians

- Championed the use of vernacular languages in education alongside English

Perhaps his most significant contribution during this period came through his involvement with the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919. These reforms introduced dyarchy in the provinces and increased Indian participation in governance—steps that, while limited, represented important progress toward self-rule. Nair’s influence on these reforms was substantial, as he authored two famous Minutes of Dissent in the Despatches on Indian Constitutional Reforms, boldly pointing out the defects of British rule and suggesting reforms that were largely accepted by the British government.

However, the defining moment of Nair’s government service came in the aftermath of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre on April 13, 1919. Horrified by the atrocity and the subsequent imposition of martial law in Punjab, Nair took the extraordinary step of resigning from the Viceroy’s Executive Council in protest. This resignation—a rare act of principled defiance by an Indian official at such a high level—sent shockwaves through the British administration and became a powerful symbol of moral courage.

His resignation triggered important changes, including:

- The lifting of press censorship in Punjab

- The termination of martial law

- The formation of the Hunter Commission to investigate the massacre

After his resignation, Nair continued to serve India in various capacities, including as a councillor to the secretary of state for India in London (1920-21) and as a member of the Indian Council of State (from 1925). Throughout these roles, he maintained his commitment to advancing Indian interests through strategic engagement with governmental institutions.

Sir Sankaran Nair’s government service exemplifies how principled individuals can work within existing systems to effect change, while also knowing when moral imperatives demand taking a stand—even at great personal cost. His career demonstrates that true service to one’s nation sometimes requires both engagement with and resistance against the powers that be.

The Historic Defamation Trial

The most dramatic chapter in Sir Sankaran Nair’s illustrious career unfolded in a London courtroom in 1924, where he faced off against Michael O’Dwyer, the former Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, in what became one of the most significant legal battles in colonial history.

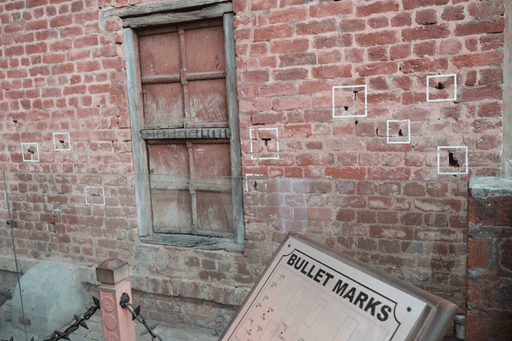

The origins of this historic confrontation lay in Nair’s book “Gandhi and Anarchy,” published in 1922. In this work, Nair made a bold accusation that reverberated throughout the British Empire: he directly held O’Dwyer responsible for the policies that led to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of April 13, 1919, where General Reginald Dyer ordered troops to fire on unarmed civilians, killing hundreds and wounding thousands.

Specifically, Nair wrote: “Before the reforms it was in the power of the Lieutenant Governor, a single individual, to commit the atrocities in the Punjab which we know only too well. He was practically uncontrolled.” This statement, along with others in the book, prompted O’Dwyer to file a defamation lawsuit against Nair in London, confident that the English judicial system would vindicate him.

The trial, which took place at the King’s Bench in London, lasted for five and a half weeks, making it the longest-running civil case of its time. Nair faced tremendous disadvantages:

- He was an Indian challenging a prominent British official

- The trial took place in London before an all-English jury

- The presiding judge, Justice Henry McCardie, showed clear bias toward O’Dwyer

- The judge openly defended General Dyer’s actions at Jallianwala Bagh

- Nair’s defense counsel was repeatedly interrupted by the judge

Throughout the trial, Nair maintained his dignified stance, refusing to back down from his assertions despite the hostile environment. The proceedings became a de facto trial of British colonial policies in India, bringing international attention to the atrocities committed at Jallianwala Bagh.

When the verdict came, the 12-member jury ruled against Nair by a vote of 11 to 1. The sole dissenting vote came from Harold Laski, a prominent Marxist political theorist. Nair was ordered to pay £500 in damages plus the expenses of the trial—a substantial sum at the time.

What followed revealed the true measure of Nair’s character. When O’Dwyer, perhaps seeking to appear magnanimous, offered to waive the financial penalty if Nair would simply apologize, Nair famously refused. He reportedly stated: “If there was another trial, who was to know if 12 other English shopkeepers would not reach the same conclusion?” This defiant response underscored his unwavering commitment to his principles despite the defeat.

The trial’s significance extended far beyond its immediate outcome. Though Nair technically lost the case, his courageous stand against O’Dwyer exposed the biases of the British judicial system and energized nationalist sentiments across India. At a time when the independence movement was gaining momentum, Indians saw in the judgment clear evidence of British prejudice against them.

Moreover, the trial brought international attention to the atrocities committed at Jallianwala Bagh, details that had remained relatively obscure despite official reports. It demonstrated that an Indian could challenge the mighty British Empire in its own courts, inspiring many others to stand against colonial injustice.

This historic legal battle, though lost in the narrow sense of the verdict, represents one of the most powerful examples of moral victory transcending legal defeat in the pursuit of justice and truth.

Impact and Legacy

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair’s impact on India’s legal landscape and freedom struggle extends far beyond his lifetime, creating ripples that continue to influence Indian jurisprudence, politics, and national identity to this day.

The most immediate impact of Nair’s courageous stand against Michael O’Dwyer was the exposure of British judicial bias to the world. The trial, widely covered in both Indian and international press, revealed the double standards of British justice when applied to colonial subjects. This exposure came at a critical juncture when global opinion was beginning to turn against imperialism, helping to erode the moral authority that Britain claimed for its colonial rule.

For the Indian independence movement, the O’Dwyer trial became a powerful symbol and rallying point. Though Nair technically lost the case, his refusal to apologize even when offered a reduction in penalties demonstrated a moral victory that resonated deeply with Indians across political divides. Nationalists pointed to the trial as evidence that justice for Indians could not be expected within the colonial system—a powerful argument for self-rule.

The trial also brought unprecedented international attention to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. Before Nair’s challenge, many details of the atrocity had remained obscured in official accounts or dismissed as necessary for maintaining order. Through the trial proceedings, the full horror of the events was laid bare before the world, making it impossible for the British to continue minimizing what had occurred.

Beyond the trial, Nair’s judicial legacy lives on in Indian courts. His progressive judgments on religious conversion, inter-caste marriage, and social reform helped establish precedents that would later inform the constitutional values of independent India. The Madras Law Journal, which he founded, continues to be an authoritative legal publication cited in courtrooms across the country.

In the realm of education, his reforms while serving on the Viceroy’s Executive Council helped lay groundwork for expanding educational access and promoting vernacular languages alongside English—principles that would later be embraced by independent India’s education policy.

His constitutional vision, particularly his advocacy for Dominion Status as a pathway to complete independence, influenced the gradual approach to decolonization that India ultimately followed. Many of the reforms he suggested in his famous Minutes of Dissent were eventually incorporated into India’s governance structure.

Perhaps most significantly, Nair exemplified a model of principled resistance that continues to inspire. His willingness to challenge injustice, even at great personal cost, demonstrated that moral courage could be as powerful a weapon against colonialism as mass movements or armed resistance.

In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in Nair’s contributions, with historians and legal scholars working to restore his rightful place in India’s freedom narrative. The recent portrayal by Akshay Kumar has brought his story to a new generation of Indians, many of whom are discovering this remarkable figure for the first time.

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi noted in April 2025 while commemorating the 106th anniversary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, Nair exemplified “the strong spirit of standing with humanity and the nation.” This enduring legacy—of courage, principle, and unwavering commitment to justice—continues to resonate in contemporary India’s ongoing journey toward fulfilling its constitutional promises.

Final Summary

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair’s extraordinary life journey from a small village in Kerala to the highest echelons of British India’s legal and administrative system, and ultimately to a London courtroom where he challenged the mighty British Empire, embodies the complex and multifaceted nature of India’s struggle for independence.

As we reflect on Nair’s contributions to India’s legal system and freedom struggle, several aspects of his legacy stand out with particular clarity. First and foremost was his unwavering commitment to principle—a quality that defined his actions as a judge, administrator, Congress president, and private citizen. When confronted with the atrocities at Jallianwala Bagh, he did not hesitate to resign from his prestigious position on the Viceroy’s Executive Council. When offered the chance to apologize to O’Dwyer in exchange for financial relief, he refused, preferring to bear the burden of the penalty rather than compromise his convictions.

Nair’s approach to resistance offers valuable lessons for contemporary times. He demonstrated that opposition to injustice need not always take the form of mass movements or armed struggle—it can also manifest through reasoned dissent, strategic use of existing institutions, and the courage to speak truth to power. His method of challenging the system from within, while maintaining his independence of thought and action, represents a sophisticated form of resistance that complements more direct approaches to fighting oppression.

The recent cinematic portrayal of Nair by Akshay Kumar has brought deserved attention to this often-overlooked hero of Indian independence. Yet even this renewed interest captures only a fraction of his multidimensional contributions. Beyond the dramatic courtroom confrontation with O’Dwyer lies a lifetime of progressive judgments, educational reforms, constitutional advocacy, and principled leadership that helped shape modern India.

As we continue to grapple with questions of justice, equality, and national identity in contemporary India, Sir Sankaran Nair’s legacy offers both inspiration and instruction. His story reminds us that the pursuit of justice sometimes requires standing alone, that defeat in legal terms can still represent moral victory, and that true patriotism means holding one’s own government accountable to its highest ideals.

In the final analysis, Sir C Sankaran Nair stands as a testament to the power of individual conscience in the face of systemic injustice—a reminder that history is shaped not only by mass movements and charismatic leaders but also by the quiet courage of principled individuals who refuse to be silent in the face of wrong. His legacy challenges us to learn more about the diverse strands that make up India’s freedom narrative and to recognize that the struggle for justice continues in new forms today.

As we close this exploration of Nair’s remarkable life, perhaps the most fitting tribute is to carry forward his spirit of principled resistance, reasoned dissent, and unwavering commitment to justice—qualities as necessary in our time as they were in his.

A powerful and inspiring read. It’s perfect for anyone interested in India’s freedom struggle, history, or the courage to stand up against injustice.

Today, I went to the beach front with my kids. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She put the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is completely off topic but I had to tell someone!

After I initially commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a remark is added I get 4 emails with the identical comment. Is there any means you possibly can remove me from that service? Thanks!