Article 3 of Indian Constitution empowers Parliament to reorganize states within the Union by forming new states, altering boundaries, and changing names of existing states. This provision has been instrumental in shaping India’s federal structure since independence. Let me provide a detailed analysis of this significant constitutional provision.

Table of Contents

Article Bifurcation & Textual Analysis of Article 3 of Indian Constitution

Article 3 states: “Parliament may by law—

(a) form a new State by separation of territory from any State or by uniting two or more States or parts of States or by uniting any territory to a part of any State;

(b) increase the area of any State;

(c) diminish the area of any State;

(d) alter the boundaries of any State;

(e) alter the name of any State”

The article includes a crucial proviso: “Provided that no Bill for the purpose shall be introduced in either House of Parliament except on the recommendation of the President and unless, where the proposal contained in the Bill affects the area, boundaries or name of any of the States, the Bill has been referred by the President to the Legislature of that State for expressing its views thereon within such period as may be specified in the reference or within such further period as the President may allow and the period so specified or allowed has expired.”

Additionally, two explanations clarify the scope:

- Explanation I: In clauses (a) to (e), “State” includes a Union territory, but in the proviso, “State” does not include a Union territory.

- Explanation II: The power conferred on Parliament by clause (a) includes the power to form a new State or Union territory by uniting a part of any State or Union territory to any other State or Union territory.

This bifurcation reveals five distinct powers granted to Parliament:

- Formation of new states through separation or unification

- Increasing a state’s area

- Diminishing a state’s area

- Altering state boundaries

- Changing state names

The proviso establishes two procedural requirements:

- Presidential recommendation for introducing the bill

- Referral to affected state legislature(s) for expressing views

Landmark Judicial Interpretations

Babulal Parante vs. State of Bombay

Facts: This case challenged the formation of Maharashtra and Gujarat in 1960. The petitioner argued that the Act violated Article 3 as the Bombay State Legislature wasn’t properly consulted.

Court’s Reasoning: The Supreme Court dismissed the petition, clarifying that:

- The President can set and extend the period for state legislatures to express their views

- If the period lapses without a response, Parliament can proceed

- Parliament’s decisions on state reorganization are not bound by state legislature views.

Ratio Decidendi: The Court established that while consultation with state legislatures is mandatory, their concurrence is not necessary for Parliament to proceed with state reorganization.

Berubari Union Case

Facts: This case addressed whether Parliament, under Article 3, had the authority to cede Indian territory to a foreign country when the central government decided to transfer part of the Berubari Union in West Bengal to Pakistan.

Court’s Reasoning: The Supreme Court ruled that Parliament’s powers under Article 3 did not extend to ceding Indian territory to a foreign nation. Consequently, the 9th Constitutional Amendment Act of 1960 was enacted to facilitate the transfer.

Key Observation: The Court distinguished between reorganization of states (covered by Article 3) and cession of territory to foreign countries (requiring constitutional amendment).

Haji Abdul Gani Khan vs. Union of India

Facts: This case challenged the Delimitation Commission for Jammu and Kashmir under the Delimitation Act, 2002.

Court’s Reasoning: The Supreme Court clarified that provisions of Article 3 apply to both states and Union Territories, allowing Parliament to form new states or Union Territories and alter their boundaries and names.

Implications: This judgment expanded the understanding of Article 3’s scope to include Union Territories, not just states.

Quotable Content for Examinations

From Babulal Parante vs. State of Bombay:

“Parliament’s decisions on state reorganization are not bound by state legislature views, ensuring federal flexibility.”

From Berubari Union Case:

“Parliament’s powers under Article 3 do not extend to ceding Indian territory to a foreign nation.”

Constitutional expert Granville Austin described India as an “indestructible union of destructible states,” highlighting the centralized power of reorganization vested in Parliament through Article 3.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar during Constituent Assembly debates emphasized: “The Constitution must be both unitary as well as federal according to the requirements of time and circumstances.”

Historical Context & Evolution

Article 3 was extensively debated in the Constituent Assembly on November 17-18, 1948, and October 13, 1949. The debates revealed contrasting perspectives on federalism and centralization:

Some members, like Prof. K.T. Shah, advocated for greater state autonomy, arguing that any changes should originate from and involve the affected state’s legislature and residents. He criticized the centralization of power, emphasizing the importance of a “democratic regime” seeking input from stakeholders rather than unilaterally imposing directives.

However, others countered this view, emphasizing the need for a centralized mechanism to address minority demands and ensure national unity. They argued that requiring state approval might “suppress the calls from minority groups seeking separate states,” given the challenges of securing a state’s endorsement for its separation.

The Drafting Committee, led by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, proposed amendments including a requirement for presidential consultation with affected states, which shaped Article 3 as it was finally adopted by the Assembly.

Practical Applications & Contemporary Relevance

Article 3 has been instrumental in India’s territorial reorganization:

- Linguistic Reorganization (1950s-60s): Formation of linguistic states like Maharashtra and Gujarat in 1960 from the erstwhile Bombay State.

- Creation of New States (2000): Formation of Chhattisgarh from Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand from Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand from Bihar.

- Recent Reorganizations:

- Creation of Telangana from Andhra Pradesh in 2014

- Reorganization of Jammu and Kashmir in 2019

- Transfer of Berasia tehsil from Madhya Pradesh to Chhattisgarh in 2020

- Merger of Dadra and Nagar Haveli with Daman and Diu.

- Ongoing Demands: There are continuing demands for new states, including the proposed state of Vidarbha, highlighting the enduring relevance of Article 3.

Comparative Constitutional Perspective

Article 3 reflects India’s unique approach to federalism when compared to other constitutional democracies:

- Centralized Authority: Unlike many federal systems where states have significant say in boundary changes, India’s Constitution grants Parliament exclusive authority over state reorganization, reflecting a more centralized approach.

- Consultation vs. Consent: While many federal constitutions require consent from affected states for boundary changes, Article 3 only requires consultation, not consent, prioritizing national integration over state autonomy.

- Flexibility for Evolution: Article 3 provides greater flexibility for territorial reorganization compared to many other federal constitutions, allowing India’s federal structure to evolve with changing socio-political realities.

Critical Evaluation

Strengths:

- Provides flexibility to address regional aspirations and administrative efficiency

- Enables reorganization without constitutional amendments

- Balances central authority with state consultation

- Promotes unity in diversity by accommodating linguistic and cultural identities

Limitations:

- State legislatures have only advisory roles, not veto powers

- Can potentially be used to diminish state autonomy

- Political considerations may override administrative efficiency

- May create interstate disputes over boundaries and resources

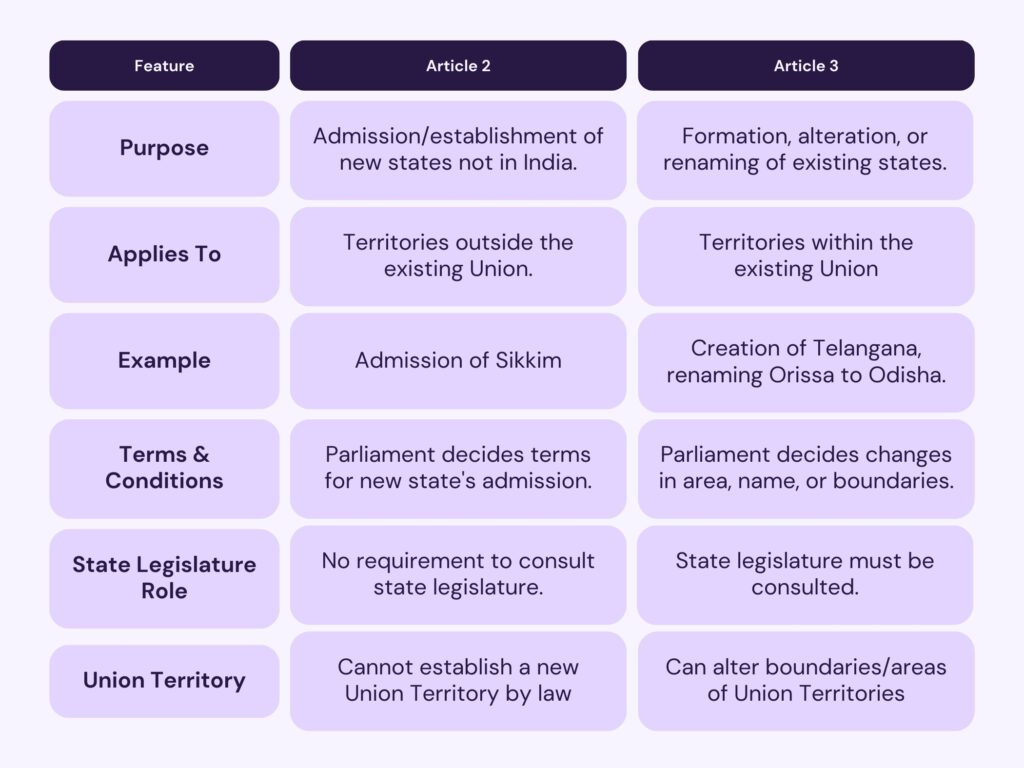

Difference Between Article 2 and Article 3 of Indian Constitution

Article 2 and Article 3 of the Indian Constitution both empower Parliament regarding the creation and modification of states, but they serve distinct purposes and operate in different contexts.

Article 2: Admission or Establishment of New States

- Scope: Article 2 empowers Parliament to admit into the Union, or establish, new states that were not previously part of India.

- Application: This article is primarily used for the integration of territories that are external to the existing territory of India. For instance, Sikkim was admitted as a state under Article 2 after it chose to join India.

- Terms and Conditions: Parliament can determine the terms and conditions for such admission or establishment, which could include governance structure, representation, and financial arrangements.

- Limitation: Article 2 does not allow Parliament to create a new Union Territory by law; this requires a constitutional amendment.

Article 3: Formation and Alteration of Existing States

Consultation Requirement: The process involves seeking the views of the state legislature affected by the change, which is not required under Article 2.

Scope: Article 3 empowers Parliament to:

Form new states by separating territory from any state or by merging two or more states or parts thereof. Increase or diminish the area of any state.

Alter the boundaries or the name of any state.

Application: Article 3 is used for internal reorganization of states within India. This includes creating new states from existing ones (e.g., Telangana from Andhra Pradesh), altering boundaries, or changing state names (e.g., Orissa to Odisha).

Procedure: A bill under Article 3 can only be introduced in Parliament on the recommendation of the President, and the concerned state legislature must be consulted (though their consent is not binding).

Synopsis

- Article 2 is about admitting or establishing entirely new states from outside the existing Indian Union.

- Article 3 is about reorganizing, altering, or renaming states that are already part of the Union.

Both articles grant significant powers to Parliament, but Article 2 deals with external integration, while Article 3 governs internal reorganization.

Examination & Advocacy Strategy

For UPSC and Judiciary Examinations:

- Distinguish Between Articles 2 and 3: Clearly articulate that Article 2 deals with admission of new states into the Union, while Article 3 concerns reorganization of existing states within the Union.

- Case-Based Answers: Use landmark cases like Babulal Parante and Berubari Union to illustrate the scope and limitations of Parliament’s powers under Article 3.

- Historical Examples: Cite specific instances of state reorganization, particularly the linguistic reorganization of states and the recent formation of Telangana.

- Connect with Federalism: Discuss how Article 3 reflects India’s unique “holding together” model of federalism, balancing national unity with regional diversity.

For Legal Advocacy:

- Challenging Reorganization: When representing clients challenging state reorganization, focus on procedural compliance with the proviso requiring Presidential recommendation and state consultation.

- Defending Reorganization: When defending reorganization, emphasize Parliament’s plenary powers under Article 3 and the non-binding nature of state legislature views.

- Territorial Disputes: In cases involving interstate boundary disputes, distinguish between reorganization under Article 3 and resolution of boundary disputes through other constitutional mechanisms.

Article 3 embodies the spirit of a living constitution, one that evolves with the needs of its people while upholding the principles of democracy and unity. As India continues to face demands for new states and alterations in state boundaries, the significance of Article 3 will only deepen, reflecting the Constitution’s enduring ability to adapt and uphold the diverse fabric of the nation.

Every line you’ve written feels like a carefully placed step on a path that leads toward greater understanding.