Article 5 of the Indian Constitution establishes the foundational criteria for determining citizenship at the commencement of the Constitution. This provision was crucial in addressing the complex citizenship questions arising from India’s independence and partition.

Table of Contents

Article Bifurcation & Textual Analysis

Article 5 states: “At the commencement of this Constitution, every person who has his domicile in the territory of India and—

(a) who was born in the territory of India; or

(b) either of whose parents was born in the territory of India; or

(c) who has been ordinarily resident in the territory of India for not less than five years immediately preceding such commencement, shall be a citizen of India.”

This provision can be bifurcated into four key components:

- Temporal Scope: The phrase “At the commencement of this Constitution” establishes that Article 5 determines citizenship status specifically at the moment the Constitution came into effect on January 26, 1950.

- Domicile Requirement: The fundamental condition is that a person must have their “domicile in the territory of India” at the Constitution’s commencement.

- Alternative Qualifying Criteria: After establishing domicile, a person must satisfy at least one of three alternative conditions:

- Birth in Indian territory (clause a)

- Parental birth in Indian territory (clause b)

- Ordinary residence in India for at least five years immediately preceding the Constitution’s commencement (clause c)

- Jus Soli Principle: Article 5 primarily embodies the jus soli or “right of soil” principle, granting citizenship based on birth or residence in Indian territory rather than solely on descent.

The phrase “shall be a citizen of India” establishes an automatic conferral of citizenship without requiring any registration or application process for those meeting the criteria.

Landmark Judicial Interpretations

Abdul Sattar Haji Ibrahim Patel v. State of Gujarat (1964)

Facts: The case involved a citizenship claim based on Article 5. The petitioner argued that all conditions in clauses (a), (b), and (c) needed to be satisfied cumulatively.

Legal Questions: Whether the requirements in clauses (a), (b), and (c) of Article 5 are cumulative or alternative.

Court’s Reasoning: The Supreme Court’s five-judge bench clarified that the basic condition under Article 5 is domicile in India, and the requirements prescribed under clauses (a), (b), and (c) are alternative in nature, not cumulative. Satisfying any one condition, along with the domicile requirement, would qualify a person for Indian citizenship.

Ratio Decidendi: “The basic condition under Article 5 is that the person must have a domicile in the territory of India and the requirements prescribed under clauses (a), (b) and (c) are alternate in nature and not cumulative.”

Firoz Meharuddin v. Sub-Divisional Officer (1960)

Facts: The case concerned individuals who met Article 5 criteria but had migrated to Pakistan after March 1, 1947.

Court’s Reasoning: The Madhya Pradesh High Court held that citizenship under Article 5 is not absolute. Individuals meeting Article 5 criteria would not be deemed Indian citizens if they migrated to Pakistan after March 1, 1947, as Article 7 overrides Article 5.

Key Observation: “Even though a person had an Indian domicile at the time of the commencement of the Constitution and fulfilled the conditions of Article 5, he would be regarded as an alien if he migrated to Pakistan after March 1, 1947.”

Kulathil Mammu v. State of Kerala (1966)

Facts: This case involved interpretation of the relationship between Articles 5, 6, and 7, particularly regarding migration to Pakistan.

Court’s Reasoning: The Supreme Court noted that Article 5 includes the concept of domicile while Articles 6 and 7 do not. The Court identified three important dates in citizenship determination:

- January 26, 1950: Those with Indian domicile on this date who satisfied Article 5 requirements would be citizens

- July 19, 1948: Related to the permit system for those returning from Pakistan

- March 1, 1947: Those who migrated to Pakistan after this date would not be considered Indian citizens even if they satisfied Article 5 conditions

Ratio Decidendi: “Article 7 will override Article 5, disqualifying from citizenship those who migrated to Pakistan after March 1, 1947, even if they otherwise satisfy Article 5 conditions.”

Quotable Content for Examinations

From Abdul Sattar Haji Ibrahim Patel v. State of Gujarat:

“The requirements prescribed under clauses (a), (b) and (c) of Article 5 are alternative in nature, not cumulative. Satisfying any one condition, along with the domicile requirement, would qualify a person for Indian citizenship.”

From Firoz Meharuddin v. Sub-Divisional Officer:

“Citizenship by virtue of Article 5 is never absolute and can be extinguished with retrospective effect if a person migrated to Pakistan after March 1, 1947.”

From Kulathil Mammu v. State of Kerala:

“The framers of the Constitution included the concept of domicile in Article 5 but deliberately excluded it from Articles 6 and 7, indicating their intention to create distinct pathways to citizenship.”

Constitutional expert Durga Das Basu observed: “Article 5 represents a unique constitutional response to the unprecedented situation created by partition, providing a clear framework for determining citizenship during this transitional period.”

Historical Context & Evolution

Article 5 was extensively debated in the Constituent Assembly on August 10, 11, and 12, 1949. The debates reflected the complex challenges of determining citizenship in the aftermath of partition.

During these discussions, some members advocated for a residuary provision based on religion, suggesting that every Hindu or Sikh not a citizen of any other state should be entitled to Indian citizenship. This proposal faced strong opposition, with arguments that citizenship should be based on justice and equity rather than religious criteria.

The historical context of Article 5 is particularly significant given the mass migration following partition. The provision needed to address the status of millions who had been displaced, while establishing clear criteria for Indian citizenship at the Constitution’s commencement.

Practical Applications & Contemporary Relevance

Article 5 had immediate practical significance in addressing citizenship status at the Constitution’s commencement:

- Domicile Determination: The concept of domicile became crucial for citizenship claims, requiring evidence of permanent residence with the intention to remain indefinitely.

- Birth Documentation: Birth certificates and other documentary evidence of birth in Indian territory became important for establishing citizenship claims.

- Ancestral Connections: Those claiming citizenship through parental birth in India needed to provide evidence of their parents’ birth in Indian territory.

- Residence Verification: For those claiming citizenship based on five years of ordinary residence, documentary evidence of continuous residence became necessary.

While Article 5 specifically addressed citizenship at the Constitution’s commencement, its principles continue to influence Indian citizenship law and jurisprudence.

Comparative Constitutional Perspective

Article 5 reflects India’s unique approach to citizenship determination:

- Hybrid Approach: Article 5 incorporates elements of both jus soli (citizenship by birth on national territory) and jus sanguinis (citizenship by descent) principles, creating a more inclusive framework than systems based solely on one principle.

- Constitutional Embedding: Unlike many countries where citizenship provisions are found in statutory laws, India incorporated fundamental citizenship criteria directly into its Constitution, reflecting the importance of this issue during the founding moment.

- Temporal Specificity: Article 5 specifically addresses citizenship at a particular moment (the Constitution’s commencement), unlike many constitutional provisions that establish ongoing rules.

Critical Evaluation of Article 5 of the Indian Constitution

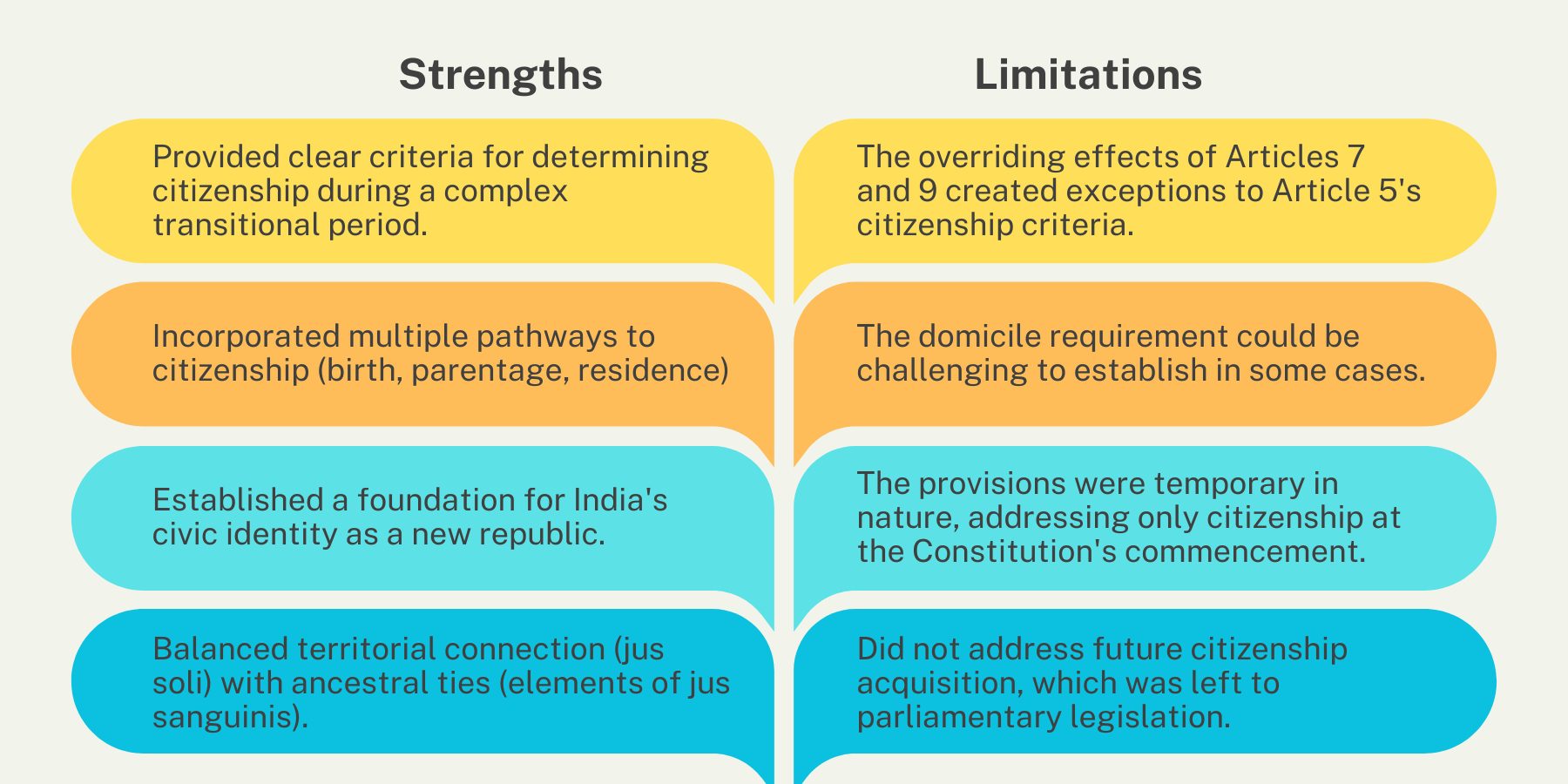

Strengths:

- Provided clear criteria for determining citizenship during a complex transitional period

- Incorporated multiple pathways to citizenship (birth, parentage, residence)

- Established a foundation for India’s civic identity as a new republic

- Balanced territorial connection (jus soli) with ancestral ties (elements of jus sanguinis)

Limitations:

- The overriding effects of Articles 7 and 9 created exceptions to Article 5’s citizenship criteria

- The domicile requirement could be challenging to establish in some cases

- The provisions were temporary in nature, addressing only citizenship at the Constitution’s commencement

- Did not address future citizenship acquisition, which was left to parliamentary legislation

Examination & Advocacy Strategy

For UPSC and Judiciary Examinations:

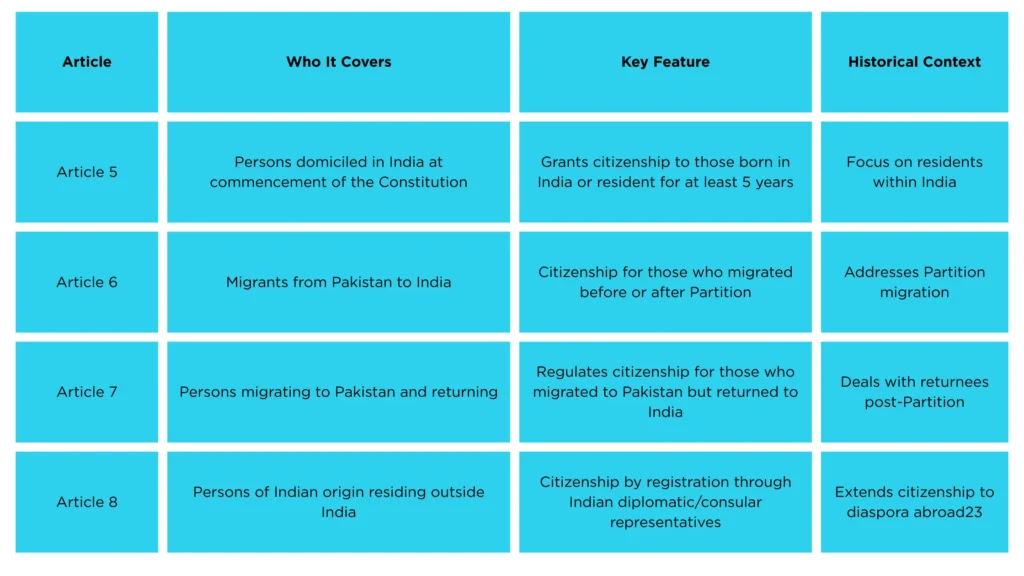

- Distinguish Between Articles 5-11: Clearly articulate that Article 5 established citizenship at the Constitution’s commencement, while subsequent articles addressed specific scenarios and Article 11 empowered Parliament to legislate on citizenship.

- Case-Based Answers: Use landmark cases like Abdul Sattar Haji Ibrahim Patel and Kulathil Mammu to illustrate the interpretation of Article 5 and its relationship with other citizenship provisions.

- Historical Context: Emphasize the unique historical circumstances of partition that necessitated constitutional provisions on citizenship rather than leaving it entirely to statutory law.

- Conceptual Clarity: Demonstrate understanding of key concepts like “domicile,” “ordinary residence,” and the distinction between alternative and cumulative conditions.

For Legal Advocacy:

- Establishing Domicile: When representing clients in citizenship cases, focus on establishing domicile through evidence of permanent residence and intention to remain indefinitely.

- Relationship with Articles 7 and 9: Address the overriding effect of Articles 7 and 9 on citizenship claims under Article 5, particularly for cases involving migration to Pakistan or acquisition of foreign citizenship.

- Documentary Evidence: Emphasize the importance of documentary evidence of birth, parentage, or residence in establishing citizenship claims.

Article 5 represents the foundational framework for Indian citizenship, reflecting the complex historical circumstances of India’s independence and the need to establish clear criteria for determining who would be recognized as citizens of the new republic. While its direct application was limited to the Constitution’s commencement, its principles continue to influence Indian citizenship law and jurisprudence.

[…] Between Articles 5, 6, and 7: Clearly articulate that Article 7 creates an exception to Articles 5 and 6 for those who […]

[…] 8 states: “Notwithstanding anything in article 5, any person who or either of whose parents or any of whose grandparents was born in India as […]

[…] Article 5: General citizenship at the commencement of the Constitution […]

[…] highlighted that Article 10 guarantees the continuance of citizenship for those recognized under Articles 5 to 9, “subject to the provisions of any law that may be made by Parliament.” The court […]