The landmark study Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) reveals one of international law’s most transformative yet overlooked chapters. Written by C.H. Alexandrowicz in 1954, this groundbreaking work illuminates how Hugo Grotius’s legal philosophy fundamentally challenged European colonial assumptions and recognized the sovereignty of Indian and Asian political entities during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Table of Contents

Understanding the Historical Context of “Grotius and India”

When examining Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History), we must first understand the revolutionary nature of Grotius’s legal reasoning. Unlike later colonial-era justifications that portrayed Asia as a legal vacuum, Grotius built upon the foundational work of Francisco de Vitoria, who had established that indigenous communities possessed inherent political organization and rights. This Spanish theological tradition, which Grotius adapted for Dutch-Portuguese relations in Asia, fundamentally rejected the notion that European powers could claim sovereignty over organized societies simply through discovery or religious conversion.

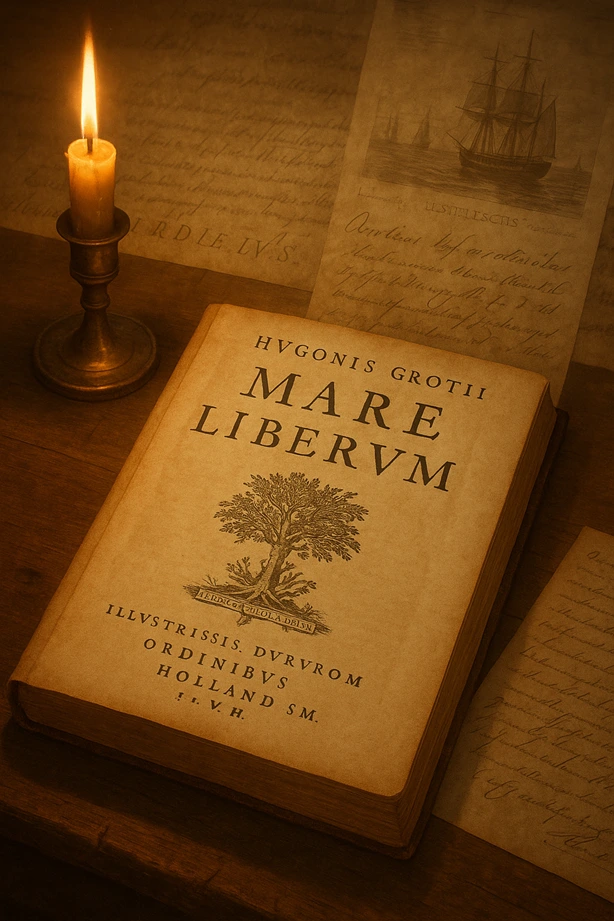

The Portuguese Empire had established the Estado da India in 1505, creating a vast network of trading posts and fortified settlements stretching from Africa to Japan. By the early 17th century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was aggressively challenging Portuguese dominance, leading to the famous capture of the Portuguese carrack Santa Catarina in 1603. This incident prompted the Dutch East India Company to commission Grotius to provide legal justification for their actions, resulting in his influential work “Mare Liberum” (The Free Sea).

The Legal Revolution: Grotius’s Recognition of Asian Sovereignty

Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) demonstrates how Grotius systematically dismantled Portuguese claims to Asian territories. In his analysis of Java, Ceylon, and the Moluccas, Grotius emphasized that these territories possessed “their own kings, state organization (res publica), and laws”. This recognition was revolutionary because it acknowledged that Asian communities had sophisticated political systems that predated European arrival by centuries.

Grotius’s legal argument was particularly significant regarding India, which he noted “had been famous for so many centuries” and therefore could not be claimed through discovery. The Dutch jurist recognized that India possessed advanced political organization, existing Christian communities, and established trade networks that demonstrated its integration into the global community of nations. This directly contradicted Portuguese claims based on papal donation or religious conversion, as Grotius noted the presence of ancient Syrian-Christian communities on the Malabar coast that predated Portuguese arrival.

The Influence of Vitoria on Grotius’s Asian Policy

Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) reveals how deeply Grotius was influenced by Francisco de Vitoria’s work on American indigenous rights. Vitoria’s famous declaration that American Indians possessed “true dominium in both public and private matters, just like Christians” provided the intellectual foundation for Grotius’s defense of Asian sovereignty. This connection between Spanish-American and Dutch-Asian legal reasoning demonstrates the early universalist tendencies in international law.

Vitoria’s emphasis on the existence of organized communities with “cities, marriages, rulers, laws, industry, and religion” became central to Grotius’s argument that Asian societies could not be treated as terra nullius (land belonging to no one). This legal principle established that only cession through treaty or conquest in a just war could provide legitimate title to Asian territories.

The Practical Application of Early International Law

The study Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) reveals how these theoretical principles played out in practice. European trading companies found themselves negotiating with sophisticated Asian political entities rather than conquering empty lands. The Portuguese conquest of Goa in 1510 and Malacca in 1511 required military campaigns against established rulers, while the Dutch capture of Malacca in 1641 involved complex alliances with local powers like the Sultanate of Johor.

These interactions demonstrate that early European expansion in Asia operated within a framework of mutual recognition and legal equality. Treaties between European companies and Asian rulers reflected this reciprocal relationship, with both sides acknowledging each other’s sovereignty and rights. This pattern of treaty-making became a foundational element of international law, establishing precedents for diplomatic relations between different civilizations.

Grotius’s Textual Evidence and Political Considerations

One of the most fascinating aspects of Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) is Alexandrowicz’s analysis of Grotius’s manuscript revisions. The original text contained passages that Grotius later crossed out, including his explicit comparison between India and America: “The reason being different in the case of India and in the case of America”. These deletions reveal the tension between Grotius’s legal principles and the political interests of the Dutch East India Company.

The crossed-out passages suggest that Grotius initially intended to provide stronger legal protection for Asian communities but modified his position to avoid undermining Dutch expansion. This tension between legal principle and political expediency reflects the complex reality of early international law development, where theoretical frameworks had to accommodate practical imperial interests.

The Decline of Equality: Colonial-Era Distortions

Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) demonstrates how later colonial writers systematically distorted the original legal framework. After European powers established territorial control in Asia, international lawyers began denying the sovereignty of Asian rulers to justify colonial domination. This represented a fundamental departure from the classic Law of Nations, which had recognized the legal equality of all organized political communities.

The transformation of international law from a framework of mutual recognition to one of colonial justification had profound implications for Asian societies. The 19th-century concept of the “Family of Nations” became increasingly exclusive, often ignoring the established political and legal systems that had existed before European colonization. This exclusion was not supported by the original legal doctrine but reflected the political realities of imperial dominance.

The Significance of Christian Communities in India

An important aspect of Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) is its discussion of pre-existing Christian communities in India. Grotius noted that Portuguese claims based on religious conversion were invalid because ancient Christian communities, particularly the Syrian Christians who claimed St. Thomas the Apostle as their founder, had existed on the Malabar coast for centuries before Portuguese arrival. This religious diversity within Indian society further undermined European claims to bring Christianity to “heathen” lands.

The peaceful coexistence of Christians, Hindus, and Muslims in pre-colonial India served as an example of religious tolerance that contrasted sharply with European religious conflicts of the period. This multicultural harmony provided additional evidence against European claims of civilizational superiority.

Contemporary Relevance and Legal Legacy

The insights from Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) remain relevant for contemporary international law and post-colonial studies. The recognition that Asian societies possessed sophisticated legal systems challenges persistent narratives about the origins of international law and the supposed European contribution to global legal development. Modern scholars increasingly recognize that international law drew from diverse global traditions rather than emerging solely from European thought.

The study also highlights the importance of examining historical legal texts in their original context rather than through later colonial interpretations. Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) demonstrates how careful textual analysis can reveal the true extent of early legal recognition for non-European societies, providing a more accurate understanding of international law’s foundations.

Reclaiming the Universal Heritage of International Law

Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) stands as a crucial corrective to Eurocentric narratives of international law development. By demonstrating that classic international law recognized the sovereignty and rights of Asian communities, Alexandrowicz’s work reveals the universal foundations of legal principles that later became distorted by colonial interests. The study shows that the exclusion of Asian societies from the “Family of Nations” was not part of the original legal doctrine but rather a later colonial-era development that contradicted established precedents.

This historical understanding has profound implications for contemporary international law, suggesting that truly universal legal principles must acknowledge the contributions and rights of all organized political communities, regardless of their cultural or religious background. The legacy of Grotius and India (from The Law of Nations in Global History) reminds us that international law at its best recognizes the inherent dignity and sovereignty of all peoples, providing a foundation for genuine equality in the global community of nations. meanwhile in 21st century New Great Powers and International Law emerged, Reshaping Global Governance

The study of “Grotius and India” continues to inform contemporary debates about sovereignty, colonialism, and the universal foundations of international legal principles.

[…] However, this fragmentation occurs within existing international legal structures rather than outside them, suggesting adaptation rather than revolution. The rise of NGPs has prompted both Old and New Great Powers to engage in regionalism, particularly in trade law, but this represents evolution within established frameworks rather than complete departure. It is interesting to know about thoughts of Grotius about India in the book The Law of Nations in Global History […]