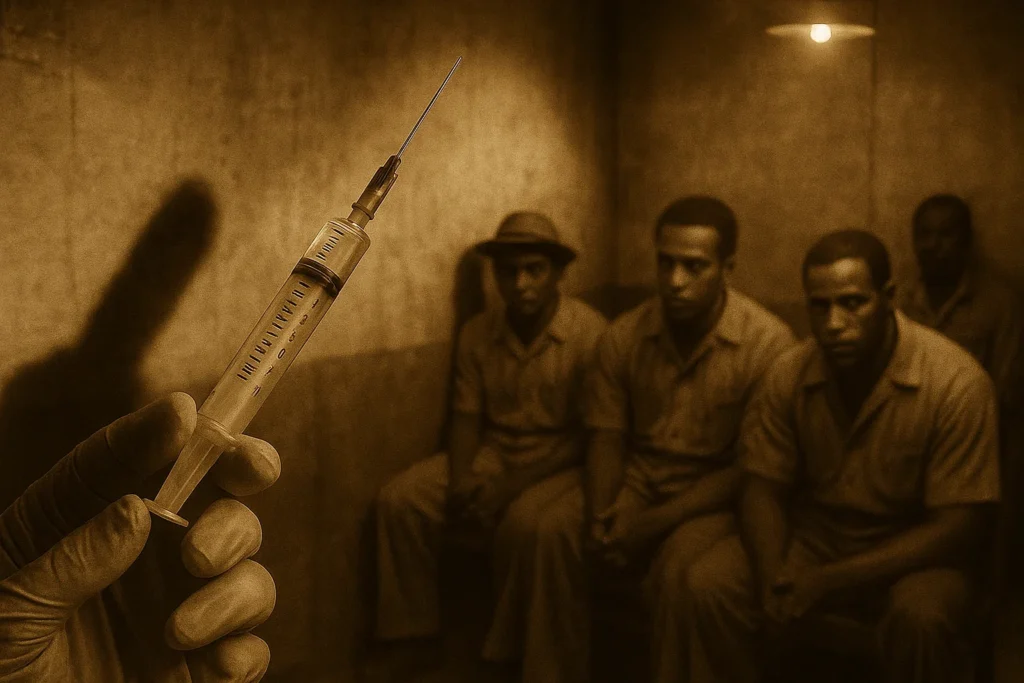

The Tuskegee Study stands as one of the most infamous and ethically reprehensible medical research projects in American history. Officially known as “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” this 40-year experiment conducted between 1932 and 1972 fundamentally changed how we approach medical research ethics and participant protection. As a research ethics student, understanding The Tuskegee Study provides critical insight into the devastating consequences of unethical research practices and the vital importance of informed consent, transparency, and respect for human dignity in scientific endeavors.

Table of Contents

The Genesis of The Tuskegee Study

The Tuskegee Study began in 1932 during the Great Depression when the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) initiated what they claimed was a six-month observational study in rural Macon County, Alabama. The study was conducted in collaboration with Tuskegee University, then known as the Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black college. The researchers enrolled 600 impoverished African American sharecroppers from the area, with 399 men having latent syphilis and 201 serving as a control group without the infection.

The ostensible purpose of The Tuskegee Study was to observe the natural progression of untreated syphilis, particularly its effects on the cardiovascular and nervous systems. However, the participants were never informed of the study’s true nature or that they had syphilis. Instead, they were told they were receiving free medical care for “bad blood,” a colloquial term that encompassed various conditions including anemia, syphilis, and fatigue.

Methodology and Deceptive Practices

The methodology employed in The Tuskegee Study was fundamentally flawed from an ethical standpoint. Participants underwent regular physical examinations, blood tests, X-rays, and spinal taps, but these procedures were presented as treatments rather than research activities. The researchers provided ineffective treatments, placebos such as aspirin, and diagnostic procedures disguised as therapeutic interventions.

To ensure participation and compliance, the USPHS offered several incentives that exploited the socioeconomic vulnerabilities of the participants. These included free medical care, free meals during examination days, and burial insurance. The burial insurance was particularly manipulative, as researchers required participants to agree to autopsy as a condition for receiving this benefit.

Variables and Study Design

From a research methodology perspective, The Tuskegee Study can be analyzed through several key variables:

Independent Variable: The presence or absence of syphilis infection

Dependent Variables: Disease progression, mortality rates, cardiovascular complications, neurological symptoms

Control Variables: Age (25-60 years), race (African American), gender (male only), geographic location (Macon County, Alabama), socioeconomic status (impoverished sharecroppers)

The study design was ostensibly a longitudinal cohort study comparing infected and uninfected participants. However, the lack of informed consent, deceptive practices, and withholding of treatment transformed it into an unethical human experiment rather than legitimate scientific research.

The Role of Deception and Medical Racism

The Tuskegee Study was deeply rooted in the racist medical beliefs prevalent in early 20th century America. Researchers operated under the assumption that African Americans were inherently promiscuous, would not seek medical treatment, and were biologically different from white populations. These prejudiced beliefs were used to justify the study’s design and continuation.

The deception employed in The Tuskegee Study was systematic and multifaceted. When penicillin became widely available as an effective treatment for syphilis in the 1940s, researchers actively prevented participants from receiving this life-saving medication. During World War II, when some participants were drafted into military service and diagnosed with syphilis, the USPHS intervened to prevent their treatment.

The Whistleblower: Peter Buxtun

The eventual exposure of The Tuskegee Study came through the courageous actions of Peter Buxtun, a 28-year-old epidemiologist and social worker employed by the Public Health Service. Buxtun first learned about the study in 1965 from colleagues and was immediately troubled by its ethical implications.

In November 1966, Buxtun filed his first official protest with the Service’s Division of Venereal Diseases, citing ethical concerns. When this was dismissed, he filed another protest in November 1968, emphasizing the political volatility of the study following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Both complaints were rejected on the grounds that the experiment was not yet complete.

After leaving the Public Health Service to pursue a law degree, Buxtun remained deeply disturbed by his knowledge of the study. In 1972, he leaked information to Associated Press reporter Jean Heller. The story was published on July 25, 1972, becoming front-page news in major newspapers and sparking national outrage.

Devastating Consequences and Human Cost

The human toll of The Tuskegee Study was catastrophic. By the time the study ended in 1972, at least 28 participants had died directly from syphilis, with estimates suggesting the actual number could be as high as 100. An additional 100 participants died from complications related to syphilis. The study’s harm extended beyond the original participants: 40 of their wives contracted syphilis, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis.

These statistics represent more than numbers; they represent families destroyed, lives cut short, and communities traumatized by medical exploitation. The study’s impact on participant families was profound and lasting, affecting multiple generations through both direct health consequences and psychological trauma.

The Broader Impact: Medical Mistrust and Public Health

The Tuskegee Study has had profound and lasting effects on African American communities’ relationship with medical institutions. Research by economists Marcella Alsan and Marianne Wanamaker revealed that disclosure of the study in 1972 led to measurable decreases in life expectancy among African American men. Their analysis found that life expectancy at age 45 for Black men fell by up to 1.4 years following the study’s revelation, accounting for approximately 35% of the 1980 life expectancy gap between Black and white men.

The phenomenon of “peripheral trauma” – adverse effects on individuals not directly involved in the study but who identified with the victims – demonstrates how The Tuskegee Study affected entire communities. This mistrust has had ongoing implications for public health initiatives, including vaccination campaigns, HIV prevention efforts, and medical research participation.

Regulatory Response: The Belmont Report and IRBs

The Tuskegee Study served as a catalyst for sweeping reforms in research ethics. The study’s exposure led directly to Congressional hearings chaired by Senator Ted Kennedy and the passage of the National Research Act in 1974. This legislation established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, which produced the landmark Belmont Report in 1979.

The Belmont Report established three fundamental ethical principles for human subjects research:

- Respect for Persons: Recognizing individual autonomy and providing special protection for those with diminished autonomy

- Beneficence: Maximizing benefits while minimizing potential harm

- Justice: Ensuring fair distribution of research benefits and burdens

These principles directly address the ethical violations perpetrated in The Tuskegee Study. The study’s lack of informed consent violated respect for persons, its withholding of treatment violated beneficence, and its targeting of vulnerable populations violated justice.

The legislation also mandated the establishment of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at all institutions receiving federal research funding. IRBs are responsible for reviewing research protocols to ensure ethical compliance, obtain informed consent, and protect participant welfare.

Modern Research Ethics Standards

Contemporary research ethics standards, largely developed in response to The Tuskegee Study and other historical violations, emphasize several key protections:

Informed Consent

Modern informed consent requirements mandate that participants receive complete information about study purposes, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives. Consent must be voluntary, without coercion, and participants must have the capacity to understand the information provided.

Continuing Review and Monitoring

Unlike The Tuskegee Study, which continued for decades without proper oversight, modern research requires regular IRB review, monitoring of adverse events, and provisions for study modification or termination when appropriate.

Vulnerable Population Protections

Special safeguards now exist for vulnerable populations, including minorities, the economically disadvantaged, and institutionalized individuals – populations specifically exploited in The Tuskegee Study.

Lessons for Contemporary Research Ethics

The Tuskegee Study continues to provide valuable lessons for modern researchers and ethicists. The study demonstrates how societal prejudices can corrupt scientific inquiry and how power imbalances between researchers and participants can lead to exploitation. It underscores the importance of community engagement, transparent communication, and ongoing ethical oversight in research involving human subjects.

The study also highlights the critical role of whistleblowers in exposing unethical practices. Peter Buxtun’s courage in speaking out, despite professional risks, ultimately saved lives and transformed research ethics. This legacy emphasizes the moral obligation of researchers and research staff to report ethical violations when they encounter them.

The Ongoing Legacy

More than five decades after The Tuskegee Study ended, its legacy continues to influence medical research and public health. The study serves as a constant reminder of the potential for abuse in research relationships and the need for vigilant ethical oversight. It has become a standard case study in research ethics education, ensuring that future generations of researchers understand the consequences of ethical failures.

The study’s impact on medical mistrust within African American communities remains relevant today, particularly in the context of COVID-19 vaccination campaigns and clinical trial recruitment. Addressing this legacy requires ongoing efforts to rebuild trust through transparency, community engagement, and diversification of the medical research workforce.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What was the main purpose of The Tuskegee Study?

A: The Tuskegee Study was designed to observe the natural progression of untreated syphilis in African American men. However, participants were never informed of this purpose and were told they were receiving treatment for “bad blood”.

Q: How long did The Tuskegee Study last?

A: The Tuskegee Study ran for 40 years, from 1932 to 1972, making it one of the longest unethical medical experiments in American history.

Q: Why didn’t participants receive penicillin treatment?

A: Although penicillin became the standard treatment for syphilis by 1947, researchers in The Tuskegee Study deliberately withheld this life-saving medication to continue observing the disease’s progression.

Q: Who exposed The Tuskegee Study?

A: Peter Buxtun, a Public Health Service employee, exposed The Tuskegee Study by leaking information to Associated Press reporter Jean Heller in 1972.

Q: What ethical principles were violated in The Tuskegee Study?

A: The Tuskegee Study violated all major ethical principles including informed consent, beneficence (do no harm), justice (fair treatment), and respect for persons.

Q: How did The Tuskegee Study change research ethics?

A: The Tuskegee Study led to the creation of the Belmont Report, establishment of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), and comprehensive federal regulations protecting human research subjects.

Q: What was the human cost of The Tuskegee Study?

A: At least 28-100 participants died from syphilis, 40 wives were infected, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis as a direct result of The Tuskegee Study.

Q: How does The Tuskegee Study affect medical research today?

A: The Tuskegee Study created lasting medical mistrust in African American communities, affecting participation in clinical trials and public health initiatives, while also establishing robust ethical oversight systems.

Q: Were any legal consequences imposed after The Tuskegee Study?

A: While no researchers were criminally prosecuted, survivors and their families received a $10 million settlement, and President Clinton issued a formal apology in 1997.

Q: What can researchers learn from The Tuskegee Study today?

A: The Tuskegee Study teaches the importance of transparency, informed consent, community engagement, and the dangers of allowing societal prejudices to influence scientific research.

Conclusion

The Tuskegee Study represents a profound failure of medical ethics that fundamentally changed how we conduct and oversee human subjects research. This 40-year experiment, built on deception, racism, and exploitation, caused immeasurable harm to participants and their communities while undermining trust in medical institutions that persists today.

The study’s exposure in 1972 catalyzed revolutionary changes in research ethics, leading to the establishment of IRBs, the Belmont Report, and comprehensive federal protections for human research subjects. These safeguards, developed directly in response to The Tuskegee Study, now protect millions of research participants worldwide.

As research ethics students and future practitioners, we must never forget the lessons of The Tuskegee Study. It reminds us that scientific progress must never come at the expense of human dignity and that ethical considerations must be paramount in all research endeavors. The courage of whistleblower Peter Buxtun also demonstrates our moral obligation to speak out against unethical practices, regardless of personal or professional costs.

The Tuskegee Study serves as both a historical cautionary tale and a contemporary call to action, reminding us that vigilant ethical oversight, community engagement, and respect for human dignity are not merely regulatory requirements but moral imperatives that must guide all research involving human participants.

Read The milgram Experiment 1963 and The Stanford Prison Experiment

[…] Read this The Tuskegee Study: A Dark Chapter in Medical Research Ethics […]