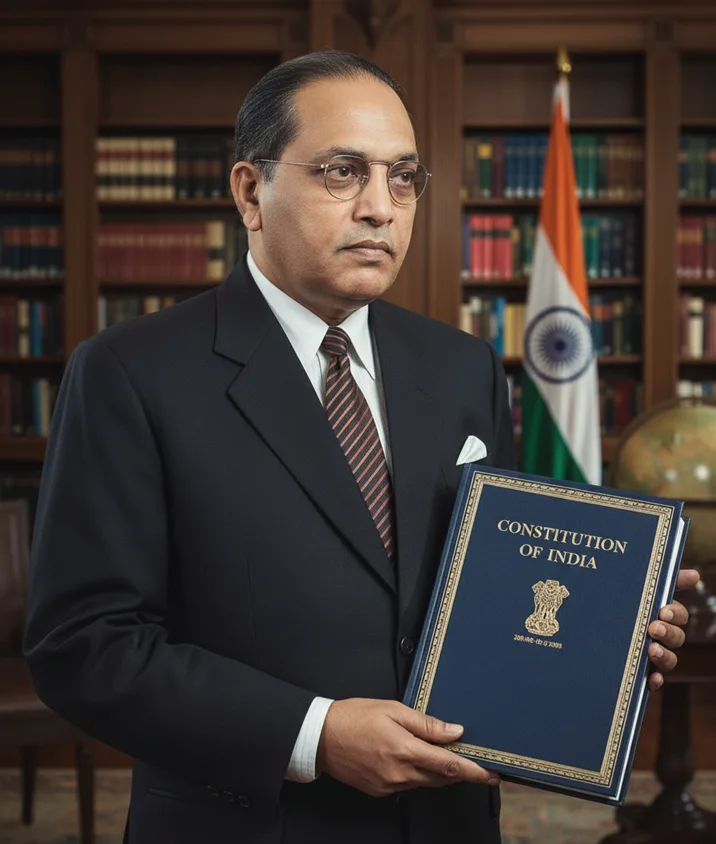

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar stands as India’s most transformative legal architect—a visionary whose constitutional genius transcended the boundaries of law to reshape the very soul of a nation. His profound declaration that “Constitutional morality is not a natural sentiment. It has to be cultivated” encapsulates not merely a legal principle, but a revolutionary philosophy that continues to guide India’s democratic journey decades after independence.

Born into the harsh realities of caste discrimination, Ambedkar transformed personal adversity into universal justice, crafting a Constitution that would serve as humanity’s beacon of hope for equality and dignity. His legacy as the Dr BR Ambedkar constitutional law pioneer extends far beyond textbooks—it lives in every fundamental right exercised, every constitutional remedy sought, and every moment of social justice achieved in modern India.

For law students, judiciary aspirants, and constitutional scholars, understanding Ambedkar legal philosophy is not optional—it’s essential for comprehending the living spirit of Indian democracy and the continuing relevance of constitutional principles in contemporary governance.

Table of Contents

Early Foundations: From Discrimination to Determination

The Crucible of Adversity

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s journey began on April 14, 1891, in Mhow, Madhya Pradesh, within the Mahar community—a caste brutally marginalized by India’s rigid social hierarchy. His childhood was marked by systematic humiliation: forced to sit separately in school, denied access to water sources, and constantly reminded of his “untouchable” status by teachers and peers alike.

Yet these very experiences of discrimination became the foundation of his constitutional vision. As Ambedkar later reflected, “Education is what makes a person aware of his existence, potential and power”. This personal understanding of injustice would profoundly shape his approach to constitutional law, ensuring that the document he would later craft would serve as a shield for the oppressed.

Academic Excellence and International Exposure

Ambedkar’s exceptional academic performance at Elphinstone High School and College marked him among the first Dalits to breach these educational barriers. His B.A. in Economics and Political Science in 1912 was just the beginning of an extraordinary intellectual journey.

The scholarship from the Maharaja of Baroda opened doors to Columbia University, where Ambedkar encountered the liberal philosophies of John Dewey and other progressive thinkers. This exposure to egalitarian principles would later influence his constitutional framework, emphasizing that social reform required the complete annihilation of discriminatory structures through law and education.

At the London School of Economics and Gray’s Inn, Ambedkar achieved the rare distinction of earning doctorates from both institutions while qualifying as a barrister. This unique combination of economic expertise and legal training equipped him with the intellectual tools necessary to architect a constitution that balanced social justice with economic pragmatism.

Did you know? Ambedkar was the first Indian to earn a doctorate in Economics from Columbia University and later became the first Law Minister of independent India.

Timeline of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s Life and Constitutional Contributions (1891-1956)

Legal Career: Pioneering Social Justice Through Law

Early Practice and Civil Rights Advocacy

Ambedkar’s legal career commenced at the Bombay High Court in 1923, where he quickly gained recognition not merely as a skilled advocate but as a crusader for civil rights. His approach to law was revolutionary—he viewed legal practice as a vehicle for social transformation rather than merely a profession.

One of his notable early successes was the 1926 defense of three non-Brahmin leaders sued for libel by the Brahmin community. This case demonstrated Ambedkar’s strategic understanding that legal victories could have broader social implications, challenging established power structures through constitutional means.

Institutional Building and Movement Leadership

Through the Bahishkrit Hitakarini Sabha, Ambedkar promoted Dalit education and upliftment, understanding that legal rights without educational empowerment would remain hollow. His publications—Mook Nayak, Bahishkrit Bharat, and Equality Janta—became powerful platforms for articulating the constitutional rights of marginalized communities.

The Mahad Satyagraha of 1927 represented Ambedkar’s practical application of constitutional principles. By demanding Dalit access to public water sources, he was essentially arguing for the constitutional principle of equality that would later become Article 15 of the Constitution. His dramatic burning of the Manusmriti during this movement symbolized the rejection of scriptures that justified caste oppression.

The Poona Pact: Constitutional Negotiation in Action

The historic Poona Pact of 1932 showcased Ambedkar’s sophisticated understanding of constitutional bargaining. When the British Communal Award granted separate electorates to Dalits, Gandhi’s fast unto death created a constitutional crisis. Ambedkar’s eventual agreement to reserved seats within joint electorates instead of separate electorates demonstrated his pragmatic approach to constitutional solutions.

This agreement secured 148 reserved seats for Scheduled Castes in provincial legislatures (nearly double the original 71) and 18% representation in the central legislature. More importantly, it established the constitutional principle of affirmative action that would later be enshrined in Articles 15(4) and 16(4) of the Constitution.

Quick Takeaway: The Poona Pact established the constitutional framework for reservations, demonstrating how Ambedkar’s legal negotiations shaped India’s approach to social justice through law.

Constitutional Architect: Crafting India’s Democratic Framework

The Drafting Committee Leadership

On August 29, 1947, Ambedkar’s appointment as Chairman of the Drafting Committee represented explicit recognition of his constitutional expertise. For 2 years and 11 months, he meticulously navigated the complex aspirations of a diverse Constituent Assembly, debating every article and incorporating over 2,473 amendments into the final document.

The magnitude of this achievement becomes clear when compared to other constitutional processes. While the American Constitution contains just 7 articles, the Canadian 147 sections, and the South African 153 sections, Ambedkar’s Constitution emerged with 395 articles in its original form. This comprehensive approach reflected his understanding that India’s diverse democracy required detailed constitutional protection for various interests and rights.

Fundamental Rights: The Constitutional Core

Ambedkar’s design of Fundamental Rights (Articles 14-18) represents perhaps his greatest constitutional contribution. These provisions weren’t merely legal technicalities—they were revolutionary social instruments designed to dismantle centuries of hierarchical oppression.

Article 14 (Right to Equality) ensures equality before law and equal protection of laws, providing the constitutional foundation for challenging arbitrary state action. This principle has become central to Indian jurisprudence, with courts using it to strike down discriminatory laws and policies.

Article 15 (Prohibition of Discrimination) outlaws discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. Crucially, Article 15(4) permits affirmative action for socially and educationally backward classes—a provision that Ambedkar insisted upon to enable constitutional correctives for historical injustices.

Article 16 (Equality of Opportunity) guarantees equal opportunity in matters of public employment while permitting reservations for backward classes under Article 16(4). This balanced approach addressed both merit-based concerns and social justice imperatives.

Article 17 (Abolition of Untouchability) declares the practice illegal and punishable by law. This provision represented Ambedkar’s direct constitutional assault on the caste system, making untouchability not just socially unacceptable but legally punishable.

Article 32: The Heart and Soul of the Constitution

Ambedkar’s famous declaration that Article 32 is “the very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it” reflects his understanding that rights without remedies are meaningless. This provision grants citizens direct access to the Supreme Court for enforcement of fundamental rights through writs including habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, certiorari, and quo warranto.

The constitutional significance of Article 32 extends beyond its immediate provisions. By enabling citizens to approach the Supreme Court directly for rights enforcement, Ambedkar created a constitutional mechanism that has enabled landmark decisions in areas ranging from environmental protection to privacy rights.

In landmark cases like Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), the Supreme Court recognized Article 32 as part of the Constitution’s basic structure, making it unamendable even by constitutional amendment. This judicial recognition validates Ambedkar’s vision of constitutional remedies as fundamental to democratic governance.

Did you know? Article 32 has been invoked in over 10,000 Supreme Court cases since 1950, making it the most frequently used constitutional provision for rights enforcement.

Social Justice and Affirmative Action Framework

Ambedkar’s constitutional provisions for social justice went far beyond prohibition of discrimination. He embedded affirmative action as a constitutional principle through:

- Reservations in Education: Article 15(4) enables special provisions for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes in educational institutions.

- Reservations in Employment: Article 16(4) permits reservations in government services for underrepresented communities.

- Political Reservations: Articles 330-342 guarantee reserved seats in Parliament and state legislatures for SCs and STs.

These provisions reflect Ambedkar legal philosophy that formal equality must be supplemented by substantive measures to address historical disadvantages.

The States and Minorities Vision: Economic Democracy

Beyond Political Rights

Ambedkar’s 1947 memorandum “States and Minorities” presented to the Constituent Assembly revealed his vision of comprehensive constitutional reform. This document, described by scholar Niraja Jayal as representing “the strongest articulation of social and economic rights,” went far beyond political representation to envision economic democracy.

The memorandum proposed:

- State ownership of key industries to prevent economic exploitation

- Land redistribution to address rural inequality

- Comprehensive social security for workers and marginalized communities

- Economic rights as fundamental constitutional entitlements

While many of these radical economic proposals weren’t fully adopted, they influenced the Directive Principles of State Policy and established the constitutional framework for India’s mixed economy approach.

Constitutional Safeguards for Minorities

Ambedkar’s conception of minority rights extended beyond religious communities to encompass all marginalized groups. His memorandum detailed specific protections including:

- Proportional representation based on population in legislatures

- Educational safeguards including separate schools and colleges where needed

- Employment protection through reservations in government services

- Cultural rights preservation for minority practices and traditions

Quick Takeaway: Ambedkar’s “States and Minorities” memorandum established the constitutional template for protecting minority rights while promoting economic justice through state intervention.

Constitutional Philosophy: Living Principles

Constitutional Morality as Governing Principle

Ambedkar’s concept of constitutional morality has become increasingly central to Indian jurisprudence. Unlike popular morality, which can be influenced by temporary prejudices and social biases, constitutional morality provides an objective standard rooted in constitutional values of liberty, equality, and dignity.

In modern Supreme Court decisions, constitutional morality has been invoked to:

- Decriminalize homosexuality in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India (2018)

- Strike down adultery laws in Joseph Shine v. Union of India (2018)

- Protect privacy rights in K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017)

- Challenge gender discrimination in Sabarimala temple entry case

This demonstrates how Ambedkar legal philosophy continues to guide contemporary constitutional interpretation, ensuring that constitutional values triumph over regressive social attitudes.

Parliamentary Democracy and Accountability

Despite initially favoring a presidential system, Ambedkar ultimately championed parliamentary democracy for its inherent accountability mechanisms. His famous observation that “the executive must be responsible to the legislature, and through it, to the people” reflects his understanding that democratic legitimacy requires continuous popular oversight.

This choice has proved prescient, as India’s parliamentary system has enabled peaceful transfers of power, coalition governments, and responsive governance despite the country’s immense diversity.

The Constitution as Living Document

Ambedkar’s vision of the Constitution as a “vehicle of life” rather than a static legal document has been validated by seven decades of constitutional evolution. His framework has adapted to address challenges ranging from linguistic reorganization to economic liberalization while maintaining its core commitment to justice and equality.

The basic structure doctrine developed by the Supreme Court in Kesavananda Bharati (1973) reflects Ambedkar’s understanding that certain constitutional principles—including judicial review, rule of law, and fundamental rights—are so essential to democratic governance that they cannot be altered even by constitutional amendment.

Social Reform Legacy: Beyond Legal Frameworks

Women’s Rights and Gender Equality

Ambedkar’s commitment to gender equality manifested most clearly in his championing of the Hindu Code Bill—legislation he considered as important as his role in framing the Constitution. This comprehensive reform sought to establish:

- Equal inheritance rights for women, converting limited estates into absolute property rights

- Right to divorce through dissolution, nullification, or invalidation of marriages

- Inter-caste marriage recognition by abolishing caste restrictions

- Maintenance rights for wives choosing to live separately

- Property rights in dowry and gifts received as absolute ownership

The bill faced fierce opposition from conservative elements, ultimately leading to Ambedkar’s resignation as Law Minister in 1951. However, his vision was eventually realized through separate acts: the Hindu Marriage Act (1955), Hindu Succession Act (1956), Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act (1956), and Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act (1956).

Did you know? The Hindu Succession Amendment Act of 2005 finally implemented Ambedkar’s 1951 vision of making daughters equal coparceners with sons in family property.

Labor Rights and Economic Justice

As Labor Minister in the Viceroy’s Executive Council (1942-1946), Ambedkar pioneered progressive labor legislation including the Factories Act of 1946 and groundwork for the Employees’ State Insurance Corporation and Employees’ Provident Fund Scheme. These measures established the constitutional principle that economic rights are essential to human dignity.

His vision of “economic democracy” influenced constitutional provisions requiring the state to ensure:

- Equal pay for equal work (Article 39(d))

- Fair and humane working conditions (Article 42)

- Living wages and decent standard of life (Article 43)

Buddhist Conversion: Religious Freedom as Constitutional Right

Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism on October 14, 1956, along with over 500,000 Dalits, represented a practical demonstration of religious freedom guaranteed under Article 25 of the Constitution. This mass conversion served multiple constitutional purposes:

- Rejecting caste-based discrimination by embracing an egalitarian religion

- Asserting dignity and self-respect through voluntary religious choice

- Creating alternative cultural spaces outside Hindu social hierarchy

- Demonstrating political consciousness and collective organization

The 22 vows administered during the conversion explicitly rejected Hindu gods and practices while affirming commitment to Buddhist principles of equality and compassion. This act established the constitutional precedent that religious conversion is a fundamental right of individual conscience.

Quick Takeaway: Ambedkar’s Buddhist conversion demonstrated how constitutional rights of religious freedom could be used to challenge social oppression and create new identities based on equality rather than hierarchy.

Constitutional Interpretation: Landmark Cases and Continuing Relevance

Basic Structure and Constitutional Supremacy

The Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) decision, while not directly citing Ambedkar, embodied his vision of constitutional supremacy over legislative power. The basic structure doctrine ensures that constitutional amendments cannot destroy the Constitution’s essential features—a principle entirely consistent with Ambedkar’s understanding that certain democratic values are non-negotiable.

Key basic structure elements identified by the Supreme Court reflect Ambedkar constitutional law principles:

- Rule of law and judicial review

- Separation of powers and institutional independence

- Fundamental rights and constitutional remedies

- Democratic governance and free elections

- Federal structure and state autonomy

Affirmative Action Jurisprudence

The Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992) judgment upholding reservations for Other Backward Classes validated Ambedkar’s constitutional framework for affirmative action. The Court’s recognition that equality requires both formal and substantive dimensions directly reflects Ambedkar legal philosophy.

In State of Kerala v. N.M. Thomas (1976), the Supreme Court affirmed that affirmative action is a tool for achieving substantive equality rather than a deviation from merit. This interpretation aligns with Ambedkar’s understanding that constitutional equality must address historical disadvantages.

Privacy and Dignity Rights

The K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017) decision recognizing privacy as a fundamental right exemplifies how Ambedkar’s constitutional framework continues to evolve. The Court’s emphasis on human dignity as the foundation of privacy rights directly connects to Ambedkar’s vision of constitutional morality protecting individual worth.

Contemporary Constitutional Challenges

Modern constitutional dilemmas continue to be resolved through Ambedkar legal philosophy principles:

- Environmental protection cases invoke Article 21 to expand the right to life

- Gender equality decisions challenge traditional practices through constitutional morality

- Digital rights cases apply fundamental rights principles to new technologies

- Economic justice litigation seeks to implement Directive Principles through judicial interpretation

Modern Relevance: Constitutional Morality in Contemporary India

Institutional Integrity and Democratic Values

Ambedkar’s warning that “However good a Constitution may be, it is sure to turn out bad because those who are called to work it, happen to be a bad lot” resonates strongly in contemporary debates about institutional independence and constitutional governance.

His emphasis on constitutional morality provides frameworks for addressing modern challenges:

- Judicial independence requiring adherence to constitutional principles over political pressures

- Executive accountability demanding respect for constitutional limitations on power

- Legislative responsibility ensuring laws comply with constitutional values

- Citizen engagement cultivating constitutional consciousness among the public

Social Justice in Digital Age

Ambedkar legal philosophy principles apply to contemporary social justice challenges:

- Digital divide issues requiring equal access to information and opportunities

- Algorithmic bias problems demanding constitutional safeguards against discriminatory technology

- Platform governance questions invoking constitutional principles of free speech and privacy

- Data protection concerns applying dignity and autonomy principles to personal information

Global Constitutional Influence

Ambedkar’s constitutional vision influences international human rights law and comparative constitutional jurisprudence:

- Affirmative action models studied globally for addressing historical discrimination

- Constitutional remedies approaches adopted by other democratic constitutions

- Social justice frameworks influencing post-colonial constitutional design

- Minority rights protections serving as templates for diverse societies

Challenges and Critiques: Ongoing Constitutional Debates

Implementation Gaps

Despite constitutional protections, challenges remain in fully realizing Ambedkar constitutional law vision:

- Caste discrimination persisting despite Article 17’s prohibition

- Gender inequality continuing despite constitutional equality guarantees

- Economic disparities growing despite Directive Principles for social justice

- Educational access remaining unequal despite constitutional commitments

Contemporary Debates

Modern constitutional debates often invoke Ambedkar legal philosophy:

- Reservation policies facing demands for review and expansion

- Religious freedom versus equality tensions in personal law

- Economic rights demanding constitutional recognition as fundamental rights

- Environmental protection requiring balance between development and dignity

Quick Takeaway: While Ambedkar’s constitutional framework remains robust, its full implementation requires continuous effort to cultivate constitutional morality among citizens and institutions.

Key Takeaways for Legal Professionals

Essential Constitutional Principles

For judiciary aspirants and legal practitioners, mastering Dr BR Ambedkar constitutional law requires understanding:

- Fundamental Rights Integration: Articles 14-18 work together to create comprehensive equality framework

- Constitutional Remedies: Article 32 provides direct Supreme Court access for rights enforcement

- Constitutional Morality: Objective standard for interpreting constitutional provisions

- Social Justice: Affirmative action as constitutional mandate, not exception

- Living Constitution: Framework adapting to contemporary challenges while preserving core values

Examination Preparation Focus Areas

Critical topics for competitive examinations include:

- Constituent Assembly debates and Ambedkar’s specific contributions

- Fundamental Rights doctrine and its judicial interpretation

- Basic structure evolution and constitutional supremacy

- Affirmative action jurisprudence and equality principles

- Constitutional morality application in landmark cases

Practical Application in Legal Practice

Modern legal practice requires applying Ambedkar legal philosophy through:

- Public Interest Litigation using constitutional principles for social reform

- Rights-based advocacy invoking fundamental rights for marginalized clients

- Constitutional interpretation applying constitutional morality in case arguments

- Social justice litigation using affirmative action principles for equality

Did you know? Over 70% of Supreme Court cases involving fundamental rights reference Ambedkar’s constitutional vision either directly or through precedents he influenced.

The Enduring Constitutional Vision

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s legacy as the architect of Dr BR Ambedkar constitutional law transcends historical significance to provide living guidance for India’s democratic future. His declaration that the “Constitution is not a mere lawyer’s document, it is a vehicle of life, and its spirit is always the spirit of Age” continues to inspire constitutional interpretation that adapts to contemporary challenges while preserving fundamental values.

His warning remains eternally relevant: “If I find the constitution being misused, I shall be the first to burn it”. This statement reflects his understanding that constitutional documents derive legitimacy from their practical implementation of justice, not from their textual perfection.

For today’s legal professionals, Ambedkar legal philosophy offers both inspiration and instruction. His life demonstrates that law can be a transformative force for social justice when guided by constitutional morality and implemented with unwavering commitment to human dignity.

The Constitution Ambedkar crafted serves not as a monument to past achievements but as a roadmap for future progress. Every fundamental right exercised, every constitutional remedy sought, and every moment of social justice achieved validates his vision of law as the servant of human dignity and equality.

As India continues its democratic journey, Ambedkar’s constitutional legacy reminds us that the price of justice is eternal vigilance in cultivating constitutional morality among citizens, institutions, and leaders. His greatest constitutional achievement was not the document he drafted but the democratic culture he envisioned—one where constitutional values triumph over social prejudices and legal principles serve human flourishing.

In the words that continue to guide India’s constitutional conscience: “However good a Constitution may be, if those who are implementing it are not good, it will prove to be bad. However bad a Constitution may be, if those implementing it are good, it will prove to be good”. This wisdom challenges every generation to prove worthy of the constitutional democracy Ambedkar bequeathed to the nation.

Author Bio

Arunendra Singh at NLSIU Bangalore, specializing in constitutional law, intellectual property rights, and legal research methodology. With extensive experience in legal content creation and academic research, he combines scholarly rigor with practical insights to make complex legal concepts accessible to students and practitioners. His research interests include constitutional interpretation, social justice jurisprudence, and the intersection of law and technology in modern governance.

[…] Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, himself a Dalit and the principal architect of the Constitution, understood that mere legal equality wouldn’t suffice. The Constitution needed both a sword (prohibition of discrimination) and a shield (affirmative action provisions). Article 15, therefore, wasn’t just about stopping discrimination—it was about actively correcting centuries of injustice. […]