Have you ever wondered why government job advertisements mention specific percentages for different categories? Or why some positions are reserved for certain communities while others remain open to all? The answer lies in Article 16 of the Indian Constitution, one of the most significant and debated provisions that shapes employment opportunities in India’s public sector.

From a tea seller’s son becoming Prime Minister to ensuring representation of historically marginalized communities in government services, Article 16 has been instrumental in creating a more equitable society. This comprehensive guide will take you through everything you need to know about this fundamental right, its evolution, impact, and what it means for millions of Indians today.

Table of Contents

Understanding Article 16: The Basics

Article 16 guarantees equality of opportunity in matters of public employment to all citizens of India. Think of it as your constitutional right to compete fairly for any government job, from a clerk position to the highest administrative posts, without facing discrimination based on your background.

The article serves dual purposes: it ensures merit-based selection while simultaneously allowing affirmative action for historically disadvantaged communities. This balance between equality and equity has made Article 16 both celebrated and controversial.

What Does “Public Employment” Mean?

Public employment under Article 16 covers:

- Central government services

- State government positions

- Public sector undertakings

- Constitutional bodies (like Election Commission, CAG)

- Judicial services (lower judiciary)

- Defense services (except specific exemptions)

Quick Takeaways:

- Article 16 applies only to government jobs, not private sector employment

- It guarantees equal opportunity, not equal outcomes

- Both merit and social justice considerations are balanced

Historical Context and Constitutional Assembly Debates

The genesis of Article 16 lies in India’s struggle against colonial discrimination and the need to create an inclusive administrative system. During British rule, Indians faced systematic exclusion from higher administrative positions, with the civil services dominated by Europeans.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the chief architect of the Constitution, played a crucial role in shaping Article 16. During the Constituent Assembly debates on November 30, 1948, three distinct viewpoints emerged:

- Pure Merit Approach: Complete equality with no reservations

- Limited Equality: Equal opportunity without community-based reservations

- Substantive Equality: Equal opportunity with provisions for historically excluded communities

The third approach prevailed, recognizing that formal equality wasn’t sufficient to address centuries of exclusion.

The Residence Debate

Interestingly, the Assembly also debated whether states could impose residence requirements for certain positions. Some argued that local knowledge was essential for effective governance, while others felt it would undermine the concept of unified citizenship. The final provision (Article 16(3)) allowed Parliament to prescribe residence requirements for specific posts.

Did You Know? The term “backward class” was chosen over more specific terms like “Scheduled Castes” to provide flexibility for future social changes and emerging backward communities.

Detailed Analysis of Article 16 Clauses

Let’s break down each clause of Article 16 to understand its specific provisions:

Article 16(1): The Foundation

“There shall be equality of opportunity for all citizens in matters relating to employment or appointment to any office under the State”.

This is the bedrock principle ensuring every citizen has an equal chance to compete for government positions based on merit and qualifications.

Article 16(2): Non-Discrimination Guarantee

“No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth or residence, be ineligible for, or discriminated against in respect of, any employment or appointment to any office under the State”.

Note the word “only” – this means these factors cannot be the sole basis for discrimination, but they can be considered alongside other relevant criteria like qualifications and experience.

Article 16(3): Residence Requirement Exception

“Nothing in this article shall prevent Parliament from making any law prescribing, in regard to a class or classes of employment or appointment to an office under the Government of, or any local or other authority within, a State or Union territory, any requirement as to residence within that State or Union territory”.

This allows states to require local candidates for positions where regional knowledge is crucial.

Article 16(4): Backward Class Reservation

“Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State”.

This is the foundation of India’s reservation system, enabling affirmative action for underrepresented communities.

Article 16(4A): SC/ST Promotion Reservation

Added by the 77th Constitutional Amendment (1995), this allows reservation in promotions for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes if they are not adequately represented in higher positions.

Article 16(4B): Carry Forward Provision

Introduced by the 81st Amendment (2000), this allows unfilled reserved vacancies to be carried forward to subsequent years, treating them as a separate class to avoid breaching the 50% ceiling in any single year.

Article 16(5): Religious Institution Exemption

“Nothing in this article shall affect the operation of any law which provides that the incumbent of an office in connection with the affairs of any religious or denominational institution or any member of the governing body thereof shall be a person professing a particular religion or belonging to a particular denomination”.

This allows religious institutions to appoint persons of their faith for religious roles.

Article 16(6): EWS Reservation

Added by the 103rd Amendment (2019), this provides up to 10% reservation for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) in the general category, independent of existing quotas.

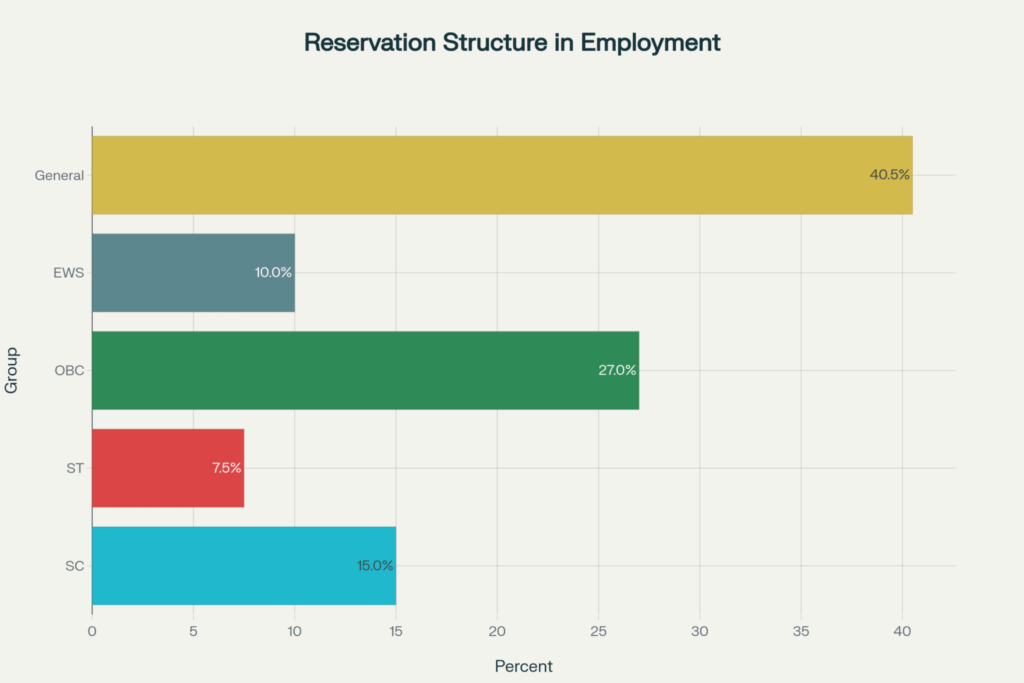

Current reservation structure showing percentage distribution across different categories in Indian public employment under Article 16

Quick Takeaways:

- Article 16 has evolved through six sub-clauses over seven decades

- Each clause addresses specific aspects of equality and representation

- The amendments reflect changing social needs and judicial interpretations

The 50% Reservation Ceiling: Indra Sawhney Case

The landmark Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992) case, also known as the Mandal verdict, fundamentally shaped how we understand Article 16 today.

Background of the Case

In 1990, the V.P. Singh government decided to implement the Mandal Commission’s recommendation of 27% reservation for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in central government jobs. This decision sparked nationwide protests and legal challenges.

Indra Sawhney, an advocate, filed a Public Interest Litigation challenging this implementation, arguing that:

- Caste-based reservations violated equality principles

- Such extensive reservations would compromise administrative efficiency

- The move was politically motivated rather than constitutionally sound

The Supreme Court’s Historic Ruling

A nine-judge Constitution bench delivered a comprehensive judgment that established several key principles:

1. The 50% Ceiling Rule

The Court declared that total reservations must never exceed 50% of available positions, calling this limit “fair and reasonable.” While not providing detailed justification, the Court stated this could be breached only in “extraordinary circumstances”.

2. Article 16(4) is Not an Exception

Contrary to earlier interpretations, the Court ruled that Article 16(4) is not an exception to Article 16(1) but rather “an instance of classification implicit in and permitted by clause (1)”. This meant reservation was not contradictory to equality but a means to achieve it.

3. The Creamy Layer Concept

The Court introduced the “creamy layer” exclusion, stating that socially advanced members of backward classes must be excluded from reservation benefits to ensure they reach truly disadvantaged individuals.

4. Caste as Valid Indicator

The Court upheld caste as a valid indicator of social backwardness, while also allowing states to use other criteria like occupation and economic status.

5. No Reservation in Promotions

The original judgment ruled that reservations should not extend to promotions, though this was later modified by constitutional amendments.

Current Reservation Structure

Quick Takeaways:

- The 50% ceiling applies to SC, ST, and OBC reservations combined

- EWS reservation is treated separately, allowing total reservations to exceed 50%

- The creamy layer concept ensures benefits reach the genuinely disadvantaged

Economic Weaker Sections (EWS) Reservation

The 103rd Constitutional Amendment (2019) introduced a revolutionary concept in India’s reservation system: economic criteria as the sole basis for affirmative action.

What is EWS Reservation?

EWS reservation provides 10% quota in government jobs and educational institutions for economically disadvantaged sections of the general category (those not covered under SC, ST, or OBC quotas).

Eligibility Criteria for EWS

To qualify for EWS benefits, a candidate must meet all the following conditions:

Family Definition for EWS

- The applicant

- Parents

- Siblings below 18 years

- Spouse and children below 18 years

Constitutional Validity: Janhit Abhiyan Case (2022)

The Supreme Court upheld EWS reservation by a 3:2 majority in the Janhit Abhiyan case, addressing several constitutional challenges:

Key Arguments Against EWS:

- Violated the 50% reservation ceiling

- Economic criteria alone insufficient for reservation

- Exclusion of SC/ST/OBC from EWS benefits was discriminatory

- Breach of basic structure doctrine

Court’s Response:

- 50% ceiling applies only to SC/ST/OBC reservations, not EWS

- Economic backwardness is a valid ground for affirmative action

- SC/ST/OBC communities already have multiple constitutional benefits

- EWS reservation advances Article 14’s substantive equality

Impact of EWS Reservation

Positive Effects:

- Provides opportunities to economically disadvantaged upper castes

- Reduces caste-based stigma in reservations

- Addresses growing income inequality

Concerns and Criticisms:

- May benefit relatively privileged sections within the general category

- Implementation challenges in income verification

- Potential dilution of existing reservation benefits

Myth Buster: EWS reservation does not reduce existing quotas for SC, ST, or OBC communities. It is provided in addition to existing reservations, expanding the overall reservation pie.

Quick Takeaways:

- EWS is the first purely economic-based reservation in India

- It’s available only to general category candidates

- The 10% quota is separate from the traditional 50% ceiling

Article 16 vs Article 14: Key Differences

Many people confuse Article 14 and Article 16, but they serve different purposes in India’s equality framework.

Article 14: The Broader Principle

Article 14 provides the foundational right to equality – “The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India”.

Key features:

- Applies to all persons (citizens and non-citizens)

- Covers all state actions, not just employment

- Prohibits arbitrary discrimination

- Allows reasonable classification

Article 16: The Specific Application

Article 16 is a specific application of Article 14 in the context of public employment.

Key features:

- Applies only to Indian citizens

- Limited to public employment matters

- Allows reservation for backward classes

- Permits residence-based requirements

The Relationship Between Articles 14 and 16

Think of Article 14 as the genus and Article 16 as its species. Article 16 doesn’t contradict Article 14 but rather furthers its principle by ensuring substantive equality in government employment.

| Aspect | Article 14 | Article 16 |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | All persons, all state actions | Citizens only, public employment |

| Geographic Coverage | Territory of India | Public employment under state |

| Discrimination Grounds | General prohibition | Specific grounds listed |

| Affirmative Action | Limited scope | Explicit provision for reservations |

| Constitutional Position | Foundational principle | Specific application |

How They Work Together

Article 14 provides the constitutional philosophy of equality, while Article 16 translates this philosophy into practical employment policies. Both articles recognize that formal equality may not lead to substantive equality, hence they allow reasonable classification and affirmative action.

Example: If the government announces a job requiring specific educational qualifications, this classification is valid under both articles because it’s reasonable and relevant to the job requirements. However, excluding candidates based solely on their caste would violate both articles (unless it falls under Article 16’s reservation provisions).

Quick Takeaways:

- Article 16 is a specialized extension of Article 14’s equality principle

- Both articles permit reasonable classification but prohibit arbitrary discrimination

- Article 16’s reservation provisions advance Article 14’s substantive equality goals

Major Constitutional Amendments {#constitutional-amendments}

Article 16 has been amended three times since its enactment, each reflecting evolving social needs and judicial interpretations.

Timeline showing the evolution of Article 16 through constitutional amendments and landmark Supreme Court judgments from 1950 to 2022

77th Amendment (1995): Promotions for SC/ST

Background:

The original Indra Sawhney judgment prohibited reservations in promotions. However, it became evident that without promotional opportunities, SC/ST employees remained concentrated in lower positions.

Amendment Details:

- Added Article 16(4A)

- Enabled reservation in promotions for SC/ST if inadequately represented

- Required states to demonstrate backwardness and inadequate representation

Impact:

- Increased SC/ST representation in senior government positions

- Led to the Nagaraj case (2006) establishing the three-fold test

81st Amendment (2000): Carry Forward Provision

Background:

Unfilled reserved vacancies were being treated as general category positions, defeating the purpose of reservation.

Amendment Details:

- Added Article 16(4B)

- Allowed carry forward of unfilled reserved vacancies

- Treated carry-forward vacancies as separate from current year quotas

Impact:

- Ensured reserved positions don’t lapse

- Maintained reservation effectiveness over time

- Prevented gaming of the reservation system

103rd Amendment (2019): EWS Reservation

Background:

Growing demand for economic-based reservations from general category communities led to this historic amendment.

Amendment Details:

- Added Article 16(6)

- Provided 10% reservation for economically weaker sections

- Extended to both government jobs and educational institutions

Impact:

- First purely economic-based reservation in India

- Challenged traditional caste-based reservation framework

- Increased total reservation percentage beyond 50%

Proposed Future Amendments

Several amendments have been proposed but not implemented:

Private Sector Reservation:

A 2019 bill proposed extending Article 16 reservations to private sector jobs, but it hasn’t progressed.

Women’s Reservation:

While the Women’s Reservation Bill focuses on legislative representation, discussions continue about employment reservations.

Quick Takeaways:

- Each amendment addressed specific implementation challenges

- Amendments reflect changing social dynamics and judicial interpretations

- Future amendments may expand reservation scope or introduce new criteria

Landmark Supreme Court Cases

Several pivotal Supreme Court judgments have shaped our understanding and application of Article 16.

1. State of Madras v. Champakam Dorairajan (1951)

Facts: Tamil Nadu government reserved seats in medical and engineering colleges based on caste and religion.

Judgment: The Court struck down caste-based reservations in educational institutions, ruling they violated Article 29(2).

Impact: Led to the First Constitutional Amendment adding Article 15(4) to enable such reservations. Established early restrictive interpretation of equality.

2. State of Kerala v. N.M. Thomas (1975)

Facts: Kerala government provided age relaxation and exemption from entrance test for SC/ST candidates.

Judgment: The Court upheld these provisions, ruling that Article 16(4) was not an exception but an extension of Article 16(1).

Impact: Paradigm shift from formal to substantive equality. Recognized that identical treatment doesn’t ensure equal outcomes.

3. Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992)

Already covered in detail above. This remains the most significant Article 16 judgment, establishing the 50% ceiling and creamy layer concepts.

4. M. Nagaraj v. Union of India (2006)

Facts: Challenge to the constitutional validity of the 77th and 81st Amendments regarding SC/ST promotions.

Judgment: The Court upheld both amendments but established the three-fold test:

- Quantifiable data showing backwardness

- Inadequate representation in services

- Maintenance of administrative efficiency

Impact: Added procedural safeguards to promotional reservations. Required empirical justification for affirmative action.

5. Jarnail Singh v. Lachhmi Narain Gupta (2018)

Facts: Whether the Nagaraj requirement of proving backwardness applied to SC/ST.

Judgment: The Court ruled that SC/ST don’t need to prove backwardness as it’s constitutionally recognized. Only inadequate representation needs demonstration.

Impact: Simplified SC/ST promotion process while maintaining safeguards.

6. Janhit Abhiyan v. Union of India (2022)

Facts: Constitutional challenge to EWS reservation under the 103rd Amendment.

Judgment: 5-judge bench upheld EWS reservation 3:2, ruling it doesn’t violate basic structure.

Impact: Validated economic criteria for reservation. Established that 50% ceiling applies only to caste-based quotas.

Emerging Trends in Judicial Interpretation

Recent judgments show:

- Greater emphasis on data-driven reservations

- Balance between efficiency and equity

- Recognition of multiple forms of backwardness

- Flexibility in applying constitutional principles

Quick Takeaways:

- Supreme Court interpretations have significantly evolved Article 16’s scope

- Key cases established major doctrines still applied today

- Judicial approach has shifted from formalistic to substantive equality

Common Misconceptions and Myths

Let’s address some widespread misconceptions about Article 16 that often create confusion in public discourse.

Myth 1: “Article 16 Guarantees Government Jobs”

Reality: Article 16 guarantees equal opportunity to compete, not guaranteed employment. It ensures a fair selection process but doesn’t promise jobs to anyone.

Why This Matters: Understanding this distinction is crucial for realistic expectations about government employment policies.

Myth 2: “Reservations Are Against Merit”

Reality: The Supreme Court has consistently held that reservation is a facet of merit, not opposed to it. The Constitution recognizes that social disadvantages can prevent meritorious individuals from competing on equal terms.

Constitutional Perspective: Article 335 explicitly balances reservation with administrative efficiency, showing the framers intended both merit and equity.

Myth 3: “50% Reservation Limit is Constitutional Law”

Reality: The 50% ceiling is a judicial pronouncement, not constitutional text. The Constitution doesn’t specify any percentage limit, and recent EWS reservation has pushed total quotas beyond 50%.

Current Status: With EWS, total reservation can reach 59.5% (49.5% traditional + 10% EWS).

Myth 4: “Article 16 Applies to Private Companies”

Reality: Article 16 applies only to public employment – government jobs and public sector undertakings. Private companies are not bound by Article 16 reservations.

Exception: Some states have enacted laws requiring private companies to provide reservations, but these are separate from Article 16.

Myth 5: “EWS Reduces SC/ST/OBC Reservations”

Reality: EWS reservation is in addition to existing quotas, not a replacement. Traditional reservations remain unchanged.

Numerical Reality:

- Pre-EWS: 49.5% reserved, 50.5% general

- Post-EWS: 49.5% traditional reservation + 10% EWS = 59.5% total reservation, 40.5% general

Myth 6: “Creamy Layer Applies to All Reserved Categories”

Reality: The creamy layer concept currently applies only to OBCs, not SC/ST communities. However, there are ongoing debates about extending it.

Legal Basis: The Supreme Court in Indra Sawhney specifically exempted SC/ST from creamy layer exclusion.

Myth 7: “Reservation is Permanent”

Reality: While not time-bound, reservations are subject to periodic review based on changing social conditions. Article 16(4) allows reservations only for communities “not adequately represented”.

Constitutional Position: The need for reservation should theoretically diminish as representation improves.

Myth 8: “All Backward Classes Get Same Benefits”

Reality: Different categories have different provisions:

- SC/ST: Reservation in direct recruitment and promotions

- OBC: Reservation in direct recruitment only (with creamy layer exclusion)

- EWS: 10% separate quota with income criteria

Why Different Treatment: Each category faces distinct forms of disadvantage requiring tailored solutions.

Did You Know? The term “reservation” doesn’t appear in the original Article 16(4). It only mentions “provision” – showing the framers intended flexibility in implementation methods.

Quick Takeaways:

- Many Article 16 myths stem from oversimplification of complex legal principles

- Understanding factual reality helps in informed public discourse

- The Constitution balances multiple values, not just single principles

Practical Implementation and Challenges

While Article 16 provides the constitutional framework, its practical implementation involves numerous challenges and complexities that affect millions of aspirants.

How Reservation Actually Works

Step-by-Step Process:

- Position Advertisement: Government departments announce vacancies with category-wise breakdowns

- Application Process: Candidates apply under their respective categories (General, SC, ST, OBC, EWS)

- Written Examination: Common exam for all categories with same question paper

- Cut-off Determination: Separate cut-offs established for each category

- Merit List Preparation: Category-wise merit lists created

- Final Selection: Candidates selected according to reserved percentages

Category-wise Selection Example:

For 100 positions:

- General: 40-41 positions (top scorers from general category)

- OBC: 27 positions (top OBC candidates, excluding creamy layer)

- SC: 15 positions (top SC candidates)

- ST: 7-8 positions (top ST candidates)

- EWS: 10 positions (top EWS candidates)

Current Implementation Challenges

1. Data Collection and Verification

Challenge: Establishing quantifiable data on backwardness and representation as required by Nagaraj judgment.

Real Impact: States struggle to collect comprehensive data, leading to litigation and policy delays.

Potential Solution: Standardized data collection mechanisms and periodic social audits.

2. Creamy Layer Identification

Challenge: Determining which OBC individuals should be excluded from reservation benefits.

Current Issues:

- Income verification difficulties

- Different states having different creamy layer criteria

- Lack of regular updates to income limits

3. Adequate Representation Assessment

Challenge: Defining what constitutes “adequate representation” in government services.

Complexities:

- Should it be proportional to population?

- Grade-wise or service-wise representation?

- How to account for historical deficits?

4. Administrative Efficiency Balance

Challenge: Ensuring reservations don’t compromise service delivery quality as mandated by Article 335.

Ongoing Debates:

- Training and capacity building for reserved category employees

- Performance evaluation mechanisms

- Career advancement support systems

State-wise Variations

Different states have implemented Article 16 differently:

| State | Total Reservation | Special Features |

|---|---|---|

| Tamil Nadu | 69% | Exceeds 50% ceiling (pre-dates Indra Sawhney) |

| Karnataka | 56% | Separate quotas for dominant backward castes |

| Maharashtra | 52% (after SC intervention) | Maratha reservation struck down |

| Rajasthan | 50% + 10% EWS | Standard implementation |

Technology and Modern Challenges

Digital Divide Impact:

- Online applications may disadvantage rural SC/ST candidates

- Language barriers in computer-based tests

- Lack of digital literacy affecting preparation

Coaching Industry Influence:

- Expensive coaching creating new barriers

- Urban-rural divide in access to quality preparation

- Need for public sector coaching support

Success Stories and Positive Outcomes

Representation Improvements:

- SC representation in central services increased from 8.8% (1965) to 17.06% (2019)

- ST representation grew from 1.6% (1965) to 9.17% (2019)

- Women’s participation in civil services has significantly increased

Social Transformation:

- Greater diversity in government decision-making

- Improved service delivery in marginalized communities

- Enhanced social mobility for reserved categories

Recommendations for Better Implementation

1. Systematic Data Management

- Regular socio-economic surveys

- Digitized caste certificate systems

- Performance monitoring dashboards

2. Capacity Building Programs

- Pre-recruitment training for reserved category candidates

- Mentorship programs within government services

- Continuous professional development opportunities

3. Transparent Processes

- Real-time publication of selection statistics

- Regular audits of implementation

- Grievance redressal mechanisms

Quick Takeaways:

- Implementation challenges are as important as constitutional provisions

- Technology can both help and hinder equitable access

- Success requires continuous monitoring and adaptation

International Comparisons

How does India’s Article 16 reservation system compare with affirmative action policies in other democracies? Understanding global practices provides valuable perspective on India’s approach.

United States: Affirmative Action

Key Features:

- Race-conscious admissions in universities (recently restricted by Supreme Court)

- Diversity initiatives in federal employment

- Set-aside programs for minority-owned businesses

- No constitutional mandate – policy-driven approach

Differences from India:

- Primarily focused on educational opportunities

- Less emphasis on employment quotas

- More court challenges and reversals

- Individual-focused rather than group-based

Brazil: Racial and Social Quotas

Key Features:

- 50% quota in federal universities for public school students

- Racial quotas within this 50% based on regional demographics

- Income-based criteria combined with racial factors

- Recent implementation (2012 onwards)

Similarities to India:

- Constitutional backing for affirmative action

- Combination of social and economic criteria

- Significant impact on higher education demographics

Malaysia: Bumiputera Policy

Key Features:

- Preferential treatment for ethnic Malays and indigenous groups

- Quotas in higher education and government employment

- Business ownership targets and economic incentives

- Enshrined in constitution since independence

Comparison with India:

- More economically focused than India’s approach

- Ethnic rather than caste-based classification

- Less judicial oversight of implementation

South Africa: Black Economic Empowerment

Key Features:

- Employment Equity Act mandating demographic representation

- Preferential procurement for historically disadvantaged businesses

- Skills development programs for black population

- Constitutional commitment to addressing past discrimination

Lessons for India:

- Private sector inclusion more comprehensive

- Skills development integration with reservation policy

- Regular monitoring and reporting requirements

European Union: Positive Action

Key Features:

- Gender-focused positive discrimination allowed

- Disability inclusion measures mandated

- Limited scope compared to other countries

- Individual merit emphasis with diversity consideration

Contrast with India:

- Much narrower scope of beneficiaries

- Stronger emphasis on individual rights

- Less institutionalized quotas

Key Lessons for India

1. Holistic Approach Benefits

Countries with comprehensive policies (education + employment + economic opportunities) show better outcomes than those with narrow focuses.

2. Regular Review Mechanisms

Periodic assessment of policy effectiveness helps in fine-tuning and maintaining public support.

3. Private Sector Integration

Countries that include private sector participation achieve broader social transformation.

4. Skills Development Focus

Capacity building programs alongside reservations improve long-term outcomes for beneficiaries.

5. Data-Driven Policies

Robust data collection and analysis systems support evidence-based policy modifications.

What Makes India’s System Unique

Positive Aspects:

- Constitutional entrenchment provides stability

- Multiple criteria (caste, tribe, economics) address diverse disadvantages

- Long-term implementation allows for learning and refinement

- Judicial oversight maintains checks and balances

Areas for Improvement:

- Private sector integration remains limited

- Skills development could be better integrated

- Regional variations create inconsistencies

- Political debates sometimes overshadow evidence-based discussions

Quick Takeaways:

- India’s reservation system is among the world’s most comprehensive

- International experiences offer valuable lessons for improvement

- Constitutional backing provides stability but requires continuous adaptation

Future Implications and Debates

As India moves toward 2047, the 75th year of independence, what does the future hold for Article 16 and reservation policies? Several emerging trends and debates will shape its evolution.

Emerging Social and Economic Changes

1. Changing Nature of Work

- Digital economy growth creating new job categories

- Gig economy expansion blurring employment boundaries

- Remote work normalization reducing geographical barriers

- Artificial intelligence impact on government job functions

Impact on Article 16: Traditional public employment patterns may change, requiring policy adaptations for new work realities.

2. Demographic Transitions

- Urbanization acceleration affecting rural-urban representation

- Educational improvements in reserved categories

- Inter-generational mobility among beneficiary communities

- Changing social hierarchies and caste dynamics

Current Policy Debates

1. 50% Ceiling Reconsideration

Several states are challenging the 50% limit, arguing their social conditions warrant higher percentages.

Arguments For Revision:

- Changed social dynamics since 1992

- Constitutional amendments allowing flexibility

- State-specific needs requiring different approaches

Arguments Against:

- Risk of reducing general category opportunities

- Administrative efficiency concerns

- Potential for endless quota expansion

2. Private Sector Reservation Extension

Growing demands for extending reservations to private companies.

Potential Benefits:

- Broader employment opportunities for reserved categories

- Reduced burden on public sector

- More comprehensive social transformation

Challenges:

- Constitutional limitations on private entity regulation

- Economic efficiency concerns

- Implementation complexity

3. Creamy Layer Expansion

Debates on extending creamy layer concept to SC/ST communities.

Proponents Argue:

- Ensures benefits reach genuinely disadvantaged

- Prevents elite capture within communities

- More efficient resource utilization

Opponents Counter:

- SC/ST face unique discrimination regardless of economic status

- May reduce overall community representation

- Constitutional recognition of permanent disadvantage

Technology and Future Challenges

1. Digital Governance Impact

- E-governance expansion changing government job requirements

- AI and automation affecting traditional clerical positions

- Skill requirements evolution in public services

- Digital divide affecting rural reserved category candidates

2. Data Analytics and Policy

- Big data capabilities for better policy targeting

- Machine learning applications in identifying beneficiaries

- Predictive analytics for policy impact assessment

- Privacy concerns in data collection and usage

Potential Constitutional and Legal Developments

1. Possible Constitutional Amendments

- Women’s reservation in employment (beyond legislative representation)

- Economic criteria integration across all reservation categories

- Time limits on reservation provisions

- Performance-based quota adjustments

2. Judicial Trends

- Larger bench references for major policy questions

- Data-driven judgments requiring empirical evidence

- Balancing multiple constitutional values

- International law influences on equality jurisprudence

Scenario Planning for 2047

Optimistic Scenario: Successful Transformation

- Adequate representation achieved across communities

- Merit and equity balanced effectively

- Reservation needs reduced due to social progress

- New challenges addressed proactively

Realistic Scenario: Continued Evolution

- Gradual policy modifications based on changing needs

- Technology integration improving implementation

- Regional variations accommodated within constitutional framework

- Ongoing debates on specific provisions

Challenging Scenario: Increased Polarization

- Political exploitation of reservation issues

- Court interventions increasing due to policy conflicts

- Economic efficiency concerns growing

- Social harmony challenges in implementation

Recommendations for Future Policy

1. Regular Constitutional Review

- Decadal assessment of Article 16’s effectiveness

- Data-driven policy modifications

- Stakeholder consultations across communities

- International best practices integration

2. Technology Leverage

- AI-powered analysis of representation patterns

- Blockchain-based certificate verification systems

- Online platforms for transparent implementation

- Digital skills programs for reserved categories

3. Comprehensive Approach

- Education-employment-economic opportunity integration

- Private sector partnership development

- Skills development emphasis alongside reservations

- Regional customization within national framework

What do you think? Should India move toward time-bound reservations, or do structural inequalities require permanent affirmative action? Share your thoughts on how Article 16 should evolve for future generations.

Quick Takeaways:

- Article 16’s future depends on balancing multiple evolving challenges

- Technology will play an increasing role in implementation

- Constitutional review and adaptation will be necessary

- Success requires evidence-based policy making and social consensus

Frequently Asked Questions

Based on the most commonly searched queries about Article 16, here are detailed answers to help clarify key concepts:

1. What is the 50% reservation ceiling in Article 16?

The 50% reservation ceiling is a Supreme Court-imposed limit established in the Indra Sawhney case (1992). The Court ruled that total reservations for SC, ST, and OBC categories combined should not exceed 50% of available positions.

Key Points:

It’s a judicial pronouncement, not constitutional text

Applies to traditional caste-based reservations only

Can be breached in “extraordinary circumstances”

EWS reservation (10%) is separate from this ceiling

Current Reality: With EWS inclusion, total reservations can reach 59.5% (49.5% traditional + 10% EWS).

2. Who is eligible for EWS reservation under Article 16?

EWS reservation is available to general category candidates who meet specific economic criteria:

Income Limit: Annual family income less than ₹8 lakh from all sources

Asset Limits:

Agricultural land: Less than 5 acres

Residential flat: Not more than 1,000 sq ft

Residential plot (notified areas): Not more than 100 sq yards

Residential plot (non-notified areas): Not more than 200 sq yards

Important: All conditions must be satisfied simultaneously. Family includes applicant, parents, siblings under 18, spouse, and children under 18.

3. What is the difference between Article 14 and Article 16?

| Aspect | Article 14 | Article 16 |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | All state actions | Public employment only |

| Beneficiaries | All persons | Citizens only |

| Focus | General equality principle | Employment-specific equality |

| Reservations | Limited provision | Explicit reservation powers |

| Geographic Coverage | Entire territory of India | Employment under the state |

Relationship: Article 16 is a specific application of Article 14’s broader equality principle in the employment context.

4. Can Article 16 reservation exceed 50%?

Yes, but with conditions:

Traditional Reservations (SC/ST/OBC): Generally cannot exceed 50% except in extraordinary circumstances as per Indra Sawhney judgment.

EWS Reservations: 10% additional quota separate from the 50% ceiling, as upheld by the Supreme Court in Janhit Abhiyan case (2022).

State Variations: Some states like Tamil Nadu have 69% reservation due to pre-existing laws that predate the Indra Sawhney judgment.

5. What are the conditions for SC/ST promotion under Article 16(4A)?

The Nagaraj case (2006) established requirements for SC/ST promotional reservations:

Three-Fold Test:

Quantifiable data showing inadequate representation in higher positions

Backwardness assessment (later exempted for SC/ST in Jarnail Singh case)

Administrative efficiency consideration as per Article 335

Simplified After Jarnail Singh (2018):

SC/ST don’t need to prove backwardness

Only inadequate representation needs demonstration

Administrative efficiency must be maintained

6. How does the creamy layer concept apply to Article 16?

Creamy Layer applies only to OBCs, not SC/ST communities:

For OBCs:

Socially and economically advanced members excluded from reservation

Income and position-based criteria determine exclusion

Regular review of creamy layer limits required

Ensures benefits reach genuinely disadvantaged

For SC/ST:

No creamy layer exclusion currently

All community members eligible regardless of economic status

Based on recognition of unique forms of discrimination

7. What was the impact of the Indra Sawhney case on Article 16?

The Indra Sawhney judgment (1992) was transformative for Article 16 interpretation:

Major Impacts:

Established 50% reservation ceiling

Introduced creamy layer concept

Validated 27% OBC reservation

Clarified Article 16(4) as extension, not exception to 16(1)

Prohibited reservation in promotions (later modified by amendments)

Upheld caste as valid backwardness indicator

Long-term Effects:

Shaped modern reservation policy

Influenced subsequent constitutional amendments

Provided framework for balancing equality and equity

8. Can private companies be forced to follow Article 16 reservation?

No, Article 16 doesn’t apply to private companies. It covers only public employment under central/state governments.

Current Status:

No constitutional mandate for private sector reservations

Some state laws require private sector quotas

Proposed bills for private sector inclusion haven’t been enacted

CSR activities sometimes include diversity initiatives voluntarily

Exception: Government contracts and tenders may have reservation requirements for vendors and service providers.

9. What is the three-fold test for reservation under Article 16?

The three-fold test from Nagaraj case (2006) requires states to establish:

Backwardness of the Class: Quantifiable data showing social and educational disadvantage

Exempted for SC/ST in Jarnail Singh case (2018)

Still applicable for OBC and other backward classes

Inadequate Representation: Statistical evidence of underrepresentation in services

Grade-wise and service-wise analysis required

Comparison with population proportion or service requirements

Administrative Efficiency: Demonstration that reservations don’t compromise service delivery

Training and capacity building measures

Performance monitoring systems

10. How does Article 16(6) affect existing reservations?

Article 16(6) [EWS reservation] is additional, not replacement:

No Impact on Existing Quotas:

SC/ST/OBC percentages remain unchanged

EWS is 10% separate quota from general category

Total reservation increases rather than redistributes

New Dynamics:

General category effective quota reduced from ~50% to ~40%

Competition intensity changes across categories

Selection patterns may shift due to additional reserved positions

Constitutional Position: Supreme Court in Janhit Abhiyan case (2022) confirmed EWS doesn’t violate existing community rights.

Key Takeaways and Conclusion

As we reach the end of this comprehensive journey through Article 16 of the Indian Constitution, let’s synthesize the key insights that every Indian citizen should understand about this fundamental provision.

Essential Understanding Points

1. Dual Nature of Article 16

Article 16 masterfully balances two equally important constitutional values: the principle of equality of opportunity for all citizens and the need for affirmative action to address historical disadvantages. This isn’t a contradiction but a sophisticated approach to achieving substantive equality rather than just formal equality.

2. Evolution Through Interpretation

From the restrictive interpretation in Champakam Dorairajan (1951) to the transformative Indra Sawhney judgment (1992) and the recent EWS validation (2022), Article 16 has continuously evolved to meet changing social needs while maintaining constitutional integrity.

3. Beyond Simple Quotas

Article 16 is not just about reservation percentages. It encompasses broader principles of non-discrimination, merit recognition, administrative efficiency, and social justice – creating a comprehensive framework for equitable public employment.

4. Data-Driven Implementation

Modern Article 16 jurisprudence emphasizes evidence-based policies. The Nagaraj three-fold test and subsequent cases require quantifiable data to justify affirmative action, making the system more accountable and transparent.

5. Continuing Relevance

Despite over seven decades of implementation, Article 16 remains highly relevant in contemporary India. New challenges like digital divide, economic inequality, and changing work patterns require fresh approaches within the constitutional framework.

Critical Success Factors

For Article 16 to continue serving India’s constitutional vision, several factors are essential:

Balanced Implementation

- Merit and equity must be balanced, not opposed

- Individual rights and community needs require careful consideration

- Efficiency and inclusivity should complement each other

Regular Assessment

- Periodic review of representation data

- Impact evaluation of reservation policies

- Adaptation to changing social conditions

Inclusive Dialogue

- Multi-stakeholder consultations on policy modifications

- Evidence-based debates rather than emotional arguments

- Constitutional principles guiding political discussions

Looking Ahead: Article 16 in 2047

As India approaches the centenary of independence in 2047, Article 16 will likely face new questions:

- Will traditional caste-based reservations still be necessary?

- How will technology and automation affect government employment?

- Can economic criteria alone address all forms of disadvantage?

- What role should private sector participation play in achieving equality?

These questions don’t have simple answers, but Article 16’s flexible framework and India’s constitutional democracy provide the tools to address them thoughtfully.

A Personal Reflection

Think about your own relationship with Article 16. Whether you’ve benefited from its provisions, competed against reserved candidates, or simply observed its implementation, this constitutional article has likely touched your life in some way.

The true measure of Article 16’s success isn’t in perfect implementation but in its contribution to creating a more inclusive society where every citizen has a genuine opportunity to serve the nation through public employment.

Final Thoughts

Article 16 represents one of humanity’s most ambitious experiments in constitutional social engineering. It acknowledges that formal equality isn’t enough when centuries of discrimination have created unequal starting points. Yet it also recognizes that merit and efficiency cannot be sacrificed in pursuit of social justice.

This balance – between equality and equity, between individual rights and community needs, between constitutional ideals and practical implementation – makes Article 16 both challenging and inspiring.

As citizens of democratic India, we all have a stake in ensuring that Article 16 continues to evolve in ways that honor both our constitutional values and our collective aspirations for a more perfect union.

Call to Action

Understanding Article 16 is just the beginning. Here’s how you can contribute to its positive evolution:

Stay Informed: Keep updated on policy developments and court judgments affecting Article 16

Engage Constructively: Participate in public discussions with facts and constitutional understanding

Support Evidence-Based Policies: Advocate for data-driven rather than emotion-driven reservation policies

Promote Constitutional Values: Help others understand the balance between equality and equity

Monitor Implementation: Hold governments accountable for transparent and fair implementation

What’s your perspective on Article 16? Do you see it as a necessary tool for social justice or a temporary measure that should evolve? How do you think it should adapt to meet 21st-century challenges while staying true to constitutional principles?

Share this comprehensive guide with others who want to understand one of India’s most important but complex constitutional provisions. Knowledge shared is democracy strengthened.

About the Author

This comprehensive analysis of Article 16 draws from extensive legal research, constitutional scholarship, and practical implementation insights. The content reflects current legal understanding while remaining accessible to general readers interested in India’s constitutional framework.

For the latest updates on constitutional law and government policy analysis, subscribe to our newsletter and follow our constitutional law series covering all fundamental rights in detail.

[…] Article 16 of Indian Constitution (Equality of Opportunity) […]