The digital age has fundamentally transformed how we create, share, and access information, placing copyright law at the centre of heated debates about creativity, innovation, and public access to knowledge. As students, educators, creators, and consumers navigate this complex landscape, understanding the intricacies of copyright protection and its exceptions has never been more crucial. This comprehensive exploration examines the evolution, principles, and contemporary challenges of copyright law, with particular attention to educational exceptions and international harmonization efforts.

Table of Contents

The Foundation and Core Principles of Copyright Law

Copyright law serves as one of the fundamental pillars of intellectual property protection, designed to safeguard “creations of the human mind” while simultaneously promoting the broader public interest in knowledge dissemination. At its essence, copyright prevents “free riding” on successful works by granting creators exclusive rights over their expressions while maintaining a delicate balance with public access needs.

The cornerstone principle underlying all copyright law systems is the idea-expression dichotomy. This crucial distinction means that copyright protects only the “original form of expression of ideas, not the ideas themselves”. As legal scholars emphasize, “creativity protected by copyright is in the choice and arrangement of words, musical notes, colours, shapes, and so on”. This principle ensures that while specific expressions receive protection, the underlying ideas remain freely available for others to build upon, fostering continued innovation and creativity.

Originality represents another fundamental requirement in copyright law. Works must constitute an “original creation of the author,” meaning the expression must originate from the author’s labor without requiring inventiveness. This relatively low threshold for protection encourages widespread creative output while maintaining meaningful standards for legal protection.

Modern copyright law grants owners a comprehensive bundle of exclusive rights, commonly referred to as economic rights. These typically include copying, distributing, public performance, translating, adapting, and digital transmission. Additionally, many international legal systems recognize moral rights, such as the right to claim authorship and prevent derogatory treatment of works, which generally remain with authors even when economic rights are transferred.

Historical Evolution: From Printing Presses to Digital Rights

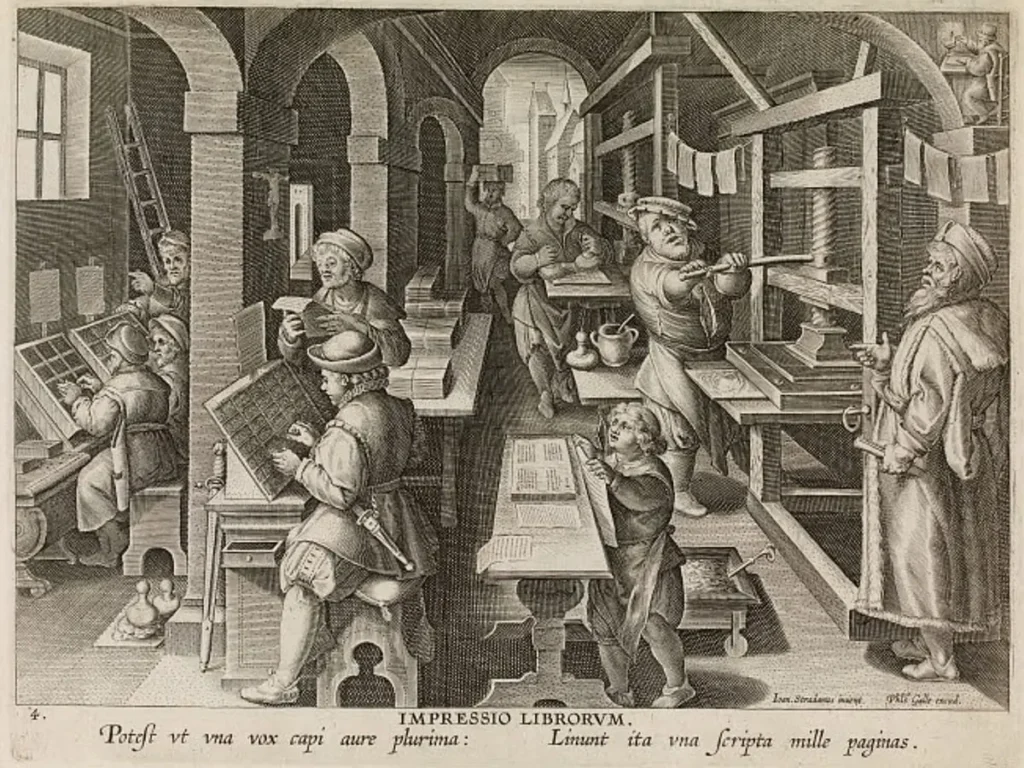

The historical development of copyright law reveals a fascinating journey from state censorship to author protection to the complex digital frameworks we navigate today. The concept of human ownership of ideas was largely absent in ancient traditions, with the conventional beginning of copyright linked to the invention of the printing press in Europe during the fifteenth century.

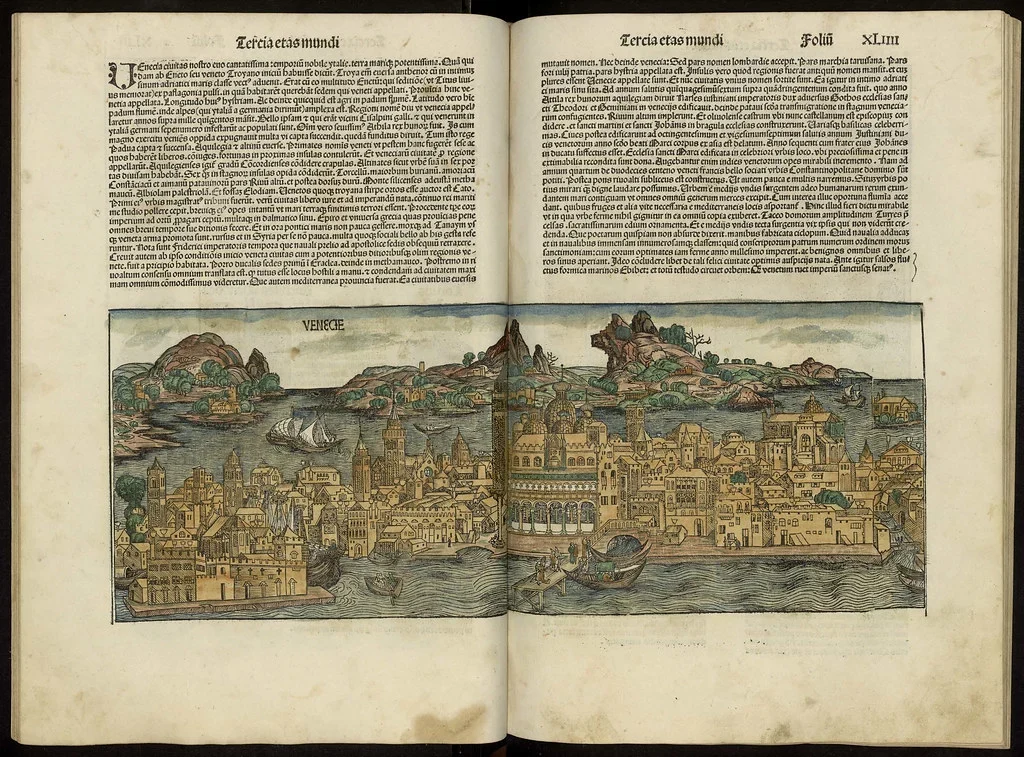

Early regulations, such as Speyer’s Monopoly (1469) and Venetian Privileges (1469), primarily granted “privileges” to print books for limited periods, initially serving state censorship and control rather than author protection. However, the landmark Statute of Anne in 1709 marked a revolutionary shift in copyright thinking. As the first copyright act to vest rights with authors rather than printers, it aimed to “abolish printing monopolies in the public interest”.

Daniel Defoe played a crucial role in advocating for this statutory protection by linking it to the “encouragement of learning” and societal benefit. The statute shifted emphasis from merely “Securing the Property of Copies in Books” to promoting learning “by Vesting the Copies of printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of such Copies”. Key features included limited protection periods (21 years for existing works, 14 years for new works with a potential second 14-year term), mandatory library deposits, and provisions for price control and foreign book importation.

This English statute “heavily influenced the US Constitution clause (1787) to ‘promote the Progress of Science and Useful Arts’ and the American Federal Copyright Act of 1790”. Subsequent judicial decisions like Donaldson v. Beckett (1774) and Wheaton v. Peters (1834) abolished common law copyright, confirming statutory protection for limited periods.

Philosophical Justifications: Why Copyright Law Matters

The theoretical foundations of copyright law rest on several compelling philosophical justifications, each offering different perspectives on why society should grant exclusive rights to creators.

Locke’s Labour Theory provides perhaps the most intuitive justification, arguing that authors deserve rewards for their “intellectual labour” or “sweat of their brow”. This theory justifies copyright as a property right, allowing authors to exploit their work provided “there is enough and as good left in common for others”. Hughes argues that intellectual property fits this condition well because ideas are “non-depletable and can be used simultaneously by an unlimited number of individuals”. The idea-expression dichotomy in copyright law connects to this theory, as “execution (expression) more clearly involves labor than the initial conception of an idea”.

Hegel’s Personality Theory offers an author-centric approach, vesting property rights in copyrighted works as “an expression of human ‘personality'”. This theory focuses on “immaterial interests (moral rights) of the author”. Hughes notes that intellectual property, being a product of mental processes, “is an ideal subject for this theory, as it directly embodies the creator’s personality”. This philosophical foundation influences concepts like moral rights and protection of unique artistic expression.

Utilitarian Theory justifies copyright law by its capacity to “promote social good by incentivising the creation and dissemination of new works”. The United States largely follows this approach, aiming for “public welfare” by rewarding authors to encourage future creations. This theory emphasizes the broader social benefits of creative production.

Economic Theory, an offshoot of utilitarianism, views copyright as a means to correct “market failures” related to intellectual goods being “public goods” (non-rivalrous and non-excludable). Copyright grants exclusive rights to compensate for these issues, “incentivising production while maintaining public access”.

Copyright Law Limitations and Exceptions: Balancing Competing Interests

The exclusive rights granted by copyright law are not absolute; they are subject to limitations and exceptions (L&Es) designed to “balance the copyright owner’s monopoly with the public interest in access to works”.

Categories of Limitations and Exceptions

Inherent Limitations include works in the public domain (expired copyright), works lacking originality, and the idea-expression dichotomy. These represent built-in boundaries to copyright protection that ensure continued access to fundamental building blocks of knowledge.

The Doctrine of Exhaustion/First Sale provides that upon the sale of a physical copy, the copyright owner cannot control its subsequent distribution, allowing resale or lending. This principle was codified in the US Copyright Act of 1909 after recognition in Bobbs-Merrill Co. v. Straus (1908).

Statutory Exceptions represent perhaps the most important category for educational and research purposes. Fair Use/Fair Dealing provisions permit unauthorised, non-remunerated use for purposes like “criticism, teaching, news reporting, private study, scholarship, or research”. Fair use involves a “case-by-case analysis using an ‘equitable rule of reason,'” considering factors like the “transformative nature of the use”.

Recent landmark cases have significantly shaped fair use doctrine. Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc. (1984) legalized time-shifting as fair use and introduced the “staple article of commerce” doctrine. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. (1994) affirmed commercial parody as fair use if transformative. Authors Guild v. Google, Inc. (2015/2016) dramatically expanded transformative fair use for large-scale digital indexing.

Educational Exceptions in Copyright Law

Educational use represents one of the most important applications of copyright law exceptions. The relationship between copyright and education has always been complex, as “the use of copyrighted materials is inevitable in educational institutions”. Educational institutions require access to copyrighted works even during the protection period, as “the goal of learning cannot wait until the copyright term comes to an end”.

Various countries have developed different approaches to educational exceptions. In the United States, Section 110(1) allows educators and students to perform or display copyrighted works in classroom settings. The TEACH Act (Technology, Education, and Copyright Harmonization Act of 2002) extends these provisions to digital education environments.

Canadian fair dealing provisions specifically include “education” as a permitted purpose. The Canadian Fair Dealing Guidelines allow teachers to communicate and reproduce “short excerpts” from copyright-protected works for educational purposes. These guidelines specify that fair dealing permits use of short excerpts for “research, private study, criticism, review, news reporting, education, satire, and parody”.

The Delhi University Photocopy Case in India demonstrated flexible application of educational exceptions, arguing against strict application of international tests to educational uses. This case upheld photocopying for teaching purposes, recognizing the crucial role of educational access in developing countries.

Justifications for Copyright Limitations and Exceptions

Legal scholars have identified six main clusters of justifications for L&Es in copyright law:

Promoting Ongoing Authorship provides “breathing room” for authors to build upon existing works, exemplified by fair use protections for parody and critical commentary.

Creating a Buffer for User Autonomy and Personal Property respects users’ interests and privacy, particularly for private, non-commercial uses like the first sale doctrine and time-shifting.

Providing Public Benefits fosters freedom of speech, access to information, and supports social policy goals such as education and accessibility for disabled persons. The Statute of Anne’s goal of “encouragement of learning” represents a historical example of this justification.

Accomplishing Economic Goals includes fostering commerce, competition, and innovation. Cases like Sega Enterprises Ltd. v. Accolade, Inc. demonstrate how reverse engineering for interoperability serves these goals.

Political Expediency acknowledges that some exceptions arise from political compromise or lobbying pressures.

Providing Flexibility recognizes that open-ended L&Es like fair use are “crucial for adapting copyright law to rapid technological and social changes”.

International Copyright Law and the Three-Step Test

The rise of international copyright law in the 19th century was driven by increased readership and piracy concerns. The development of international frameworks represents one of the most significant challenges in modern copyright harmonization.

Major International Instruments

The Berne Convention (1889) stands as the first significant international instrument, aiming to “harmonise national laws and secure copyright protection for authors globally, setting ‘minimum standards'”. However, it “primarily reflected the interests of developed nations and authors, with public interest in access being less significant”. L&Es under Berne were largely “discretionary” for member states.

The TRIPS Agreement (1995) incorporated the Berne Convention and brought intellectual property under the World Trade Organization’s trading regime, making copyright rights legally enforceable. TRIPS set “high minimum standards but made no express provision for limitations and exceptions to copyright”. The agreement was “heavily influenced by multinational corporations’ commercial interests”.

The WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT) and WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (WPPT) 1996 ushered copyright law into the digital age by introducing anti-circumvention laws to protect technological protection measures for digital works. These treaties “often prioritize private economic interests over public access”.

The Three-Step Test: A Critical Framework

The Three-Step Test represents a “fundamental concept in international copyright law that serves as a general yardstick for assessing the legitimacy of limitations and exceptions to copyright”. First introduced in Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention at the Stockholm Revision in 1967 as a “diplomatic compromise,” its status was “elevated” by subsequent agreements.

The three conditions require that exceptions must:

- Apply to ‘Certain Special Cases’: Exceptions must be “clearly defined (‘certain’) and limited in their field of application or exceptional in their scope (‘special’)”. The WTO Panel interpreted “certain” as “known and particularized” and “special” as “having an individual or limited application or purpose”.

- ‘Not Conflict with Normal Exploitation of the Work’: L&Es should not interfere with how copyright owners “derive economic value from their works”. The WTO Panel stated “normal exploitation includes both forms of exploitation that currently generate significant revenue and those that, with a certain degree of likelihood, could acquire considerable economic or practical importance in the future”.

- ‘Not Unreasonably Prejudice Legitimate Interests’: This requires balancing interests, allowing “some degree of prejudice… provided it is ‘reasonable'”. Prejudice reaches an “unreasonable level” if it causes potential “unreasonable loss of income to the copyright owner”.

The WTO Panel Report on US Section 110(5) (2000) provided the “first significant international ruling” on the three-step test. It found the “homestyle” exemption consistent but the “business” exemption inconsistent, as it was “too broad in scope” and covered a “major potential source of royalties”. This interpretation has been criticized for being “quantitative rather than qualitative,” leading to calls for more flexible approaches.

Application in National Copyright Law Systems

Different countries apply the three-step test with varying degrees of flexibility:

United States employs an “open system” of limitations through the ‘fair use’ doctrine, generally considered compliant with the three-step test due to its flexibility.

European Union maintains a “closed list” of enumerated exceptions, with the three-step test often seen as an “additional restriction” rather than an enabling provision.

United Kingdom uses a closed list of “fair dealing” provisions, which must comply with the three-step test as an overarching principle.

India applies fair dealing provisions generally consistent with the test, with cases like the Delhi University Photocopy Case demonstrating flexible interpretation for educational purposes.

Copyright Law in the Digital Age: New Challenges and Opportunities

Digitization has introduced unprecedented challenges to copyright law due to the “ease and low cost of copying and widespread internet distribution”. The digital revolution has fundamentally altered how we create, distribute, and access copyrighted content, requiring significant adaptations to traditional copyright frameworks.

Digital Rights Management and Technological Protection

Digital Rights Management (DRM) aims to combat unauthorized copying but can also “over-protect content, hindering lawful uses like lending or resale”. Legal scholar Favale argues that “DRM, as a ‘digital lock’ or ‘fence,’ must be implemented with sufficient flexibility to grant usage allowances to entitled users. If such flexibility is not technologically or economically viable, DRM should not be implemented at all”.

The challenges of digital copyright law enforcement are multifaceted. Digital piracy has become “alarmingly pervasive with the growth of streaming platforms and the accessibility of digital content”. India ranks high on the global piracy index, indicating significant losses for copyright holders due to illegal downloads and unauthorized streaming.

Artificial Intelligence and Copyright Law

The emergence of artificial intelligence has created new frontiers in copyright law. Recent 2024 and 2025 court decisions have provided initial guidance on AI training and copyright infringement. In Bartz v. Anthropic and Kadrey v. Meta, California courts found that using copyrighted works to train large language models could constitute fair use under certain circumstances.

These decisions emphasized the importance of evidence regarding infringing outputs and market impact. As Judge Chhabria noted in Kadrey, “in most cases,” training LLMs on copyrighted works without permission might be infringing, but “tweak some facts and defendants [in another case] might win”.

International Development and Copyright Law Access

Ruth L. Okediji’s research on international copyright and development argues that the current system “is fundamentally misaligned with the requirements for economic development”. Key concerns include:

Historical treaties often ignored local cultural production in colonies. “Development rhetoric” frequently “exaggerates the role of IP in economic development” while ignoring weaker IP protection during developed nations’ industrialization periods.

“Hyper-harmonisation” under Berne and strict application of the “three-step test” constrain developing countries’ ability to create robust L&Es. “Development-inducing” L&Es are needed to address issues of “scale, cost, and language,” particularly for institutions like schools, libraries, and museums crucial for “human capital formation”.

The Nollywood (Nigerian film) industry exemplifies innovation thriving “outside of copyright,” relying on informal networks and sharing. This demonstrates alternative models for creative development that don’t depend on strong copyright enforcement.

The Marrakesh Treaty: A Model for Mandatory Exceptions

The Marrakesh Treaty (2013) represents an unprecedented example of mandatory international copyright exceptions. The treaty requires all contracting parties to adopt copyright exceptions enabling creation and sharing of accessible format copies for print-disabled persons.

Implementation studies reveal that “most states have adhered closely to the Treaty’s text, thus creating a de facto global template of exceptions and limitations”. This has “increasingly enabled individuals with print disabilities, libraries and schools to create accessible format copies and share them across borders”.

The treaty demonstrates that “mandatory exceptions to copyright can reasonably coexist with robust copyright protection”. Very few countries have varied from the template to adopt additional copyright owner protections, and some have expanded exceptions to include broader disability categories.

Educational Exceptions: A Global Perspective on Copyright Law

Educational exceptions represent one of the most important and contentious areas of copyright law internationally. The tension between copyright protection and educational access reflects broader debates about knowledge accessibility and development priorities.

International Framework for Educational Copyright Exceptions

The Berne Convention provides limited guidance on educational exceptions. Article 10(1) (Quotation) is mandatory, while Article 10(2) (Illustration for Teaching) is permissive and technology-neutral. Debate continues over whether the three-step test should strictly apply to these specific exceptions under the lex specialis argument.

TRIPS does not provide specific educational exceptions but mandates the three-step test for all L&Es, shifting focus to “right holders” and trade interests, which “limits the consideration of social interests like education”.

WCT/WPPT incorporate the three-step test for digital rights but include Agreed Statements allowing states to “carry forward and appropriately extend existing limitations and exceptions into the digital environment” and “devise new exceptions”.

The stringent application of the three-step test, particularly interpretations of “normal exploitation” and “unreasonable prejudice,” can be “highly restrictive” for developing countries seeking widespread educational access. This often implies need for compensation mechanisms that are economically challenging for developing nations.

National Approaches to Educational Copyright Law

Different countries have adopted varying approaches to educational exceptions, reflecting different balances between creator rights and educational needs:

United States: The Copyright Act includes specific educational provisions like the classroom use exemption (17 U.S.C. §110(1)) and the TEACH Act. These allow performance and display of copyrighted works in educational settings under specified conditions. However, “there is no blanket exemption from copyright liability for educational uses or uses by educational institutions”.

Canada: Fair dealing provisions specifically include “education” as a permitted purpose. The Fair Dealing Guidelines allow teachers to use “short excerpts” from copyright-protected works without permission or payment. These guidelines specify amounts that constitute fair dealing for different types of works.

United Kingdom: The 2014 copyright reforms introduced a new fair dealing exception for instruction, allowing copying of works in any medium provided the use is solely to illustrate a point, is non-commercial, constitutes fair dealing, and includes sufficient acknowledgment.

Australia: The Copyright Act provides comprehensive educational exceptions, including fair dealing for research or study, copying by hand for instructional purposes, and specific provisions for educational institutions.

India: Section 52 of the Copyright Act 1957 provides exceptions for educational use, though these are more limited than some other jurisdictions. The Delhi University Photocopy Case demonstrated judicial willingness to interpret these exceptions flexibly for educational purposes.

Challenges in Educational Copyright Law Implementation

Educational institutions face numerous practical challenges in implementing copyright law compliance:

Complexity and Uncertainty: Fair use and fair dealing determinations require case-by-case analysis, creating uncertainty for educators about what uses are permissible. As one expert noted, “there are no limits on how much content may be used – no ‘safe harbour’ for duration or volume”.

Digital Transformation: The shift to online education has complicated application of educational exceptions, many of which were designed for traditional classroom settings. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this challenge, requiring rapid adaptation of copyright policies for digital learning.

Cross-Border Issues: Online education often involves students and materials from multiple jurisdictions, creating complex questions about which copyright laws apply. “Copyright is a territorial right, and different acts are permitted in different countries”.

License Override: Publishers increasingly use license terms that override statutory educational exceptions, particularly for digital materials. This “contract override” of fair use and fair dealing has become a major concern for educational institutions.

Conclusion: The Future of Copyright Law in a Digital World

As we navigate the complexities of 21st-century copyright law, the fundamental challenge remains achieving the right balance between creator rights and public access to knowledge. The historical evolution from the Statute of Anne to contemporary AI copyright disputes demonstrates copyright law’s remarkable adaptability, yet also reveals persistent tensions between competing interests.

The international harmonization of copyright law through instruments like TRIPS, WIPO treaties, and the three-step test has created unprecedented uniformity in copyright protection. However, this harmonization has often prioritized right holder interests over access concerns, particularly affecting developing countries and educational institutions.

Educational exceptions represent a critical frontier in copyright law development. As the Marrakesh Treaty demonstrates, international cooperation can successfully create mandatory exceptions that serve public welfare without undermining copyright protection. Similar approaches could address educational access needs more comprehensively.

The digital age continues to challenge traditional copyright law frameworks. Artificial intelligence, blockchain technologies, and new forms of creative expression require continued legal adaptation. Recent court decisions on AI training show both the flexibility and limitations of existing fair use frameworks.

Looking forward, copyright law must evolve to address several key challenges: ensuring meaningful educational access in both developed and developing countries, adapting to technological change while maintaining creator incentives, balancing international harmonization with local needs, and preventing contract override of statutory exceptions.

The success of the Marrakesh Treaty suggests that mandatory international exceptions, carefully crafted with stakeholder input, can serve as models for addressing other public interest concerns. Educational access, in particular, deserves similar international attention and support.

As students, educators, creators, and policymakers continue to engage with these issues, understanding the historical development, philosophical foundations, and practical applications of copyright law becomes increasingly important. The choices made today about copyright policy will shape the knowledge landscape for future generations, making informed engagement with these complex issues essential for all stakeholders.

Frequently Asked Questions About Copyright Law

Q1: What is the difference between copyright and other forms of intellectual property?

Copyright law protects original expressions of ideas in literary, artistic, musical, and other creative works, while patents protect inventions and trademark protects brand identifiers. Copyright automatically applies to eligible works upon creation, requires no registration (though registration provides additional benefits), and protects expression rather than ideas themselves.

Q2: How long does copyright protection last?

Copyright duration varies by country, but international treaties establish minimum terms. Generally, copyright lasts for the author’s life plus 50-70 years for individual creators, with different terms for corporate works. The specific duration depends on the work type, creation date, and applicable national law.

Q3: What constitutes fair use or fair dealing in educational contexts?

Educational fair use/fair dealing typically allows limited use of copyrighted materials for teaching, research, criticism, or study purposes. Key factors include the purpose of use, nature of the work, amount used, and effect on the work’s market value. Different countries apply different tests and thresholds.

Q4: Can I use copyrighted material if I don’t make money from it?

Non-commercial use is one factor in fair use analysis but doesn’t automatically make use permissible. Copyright law considers multiple factors, and even non-commercial uses can infringe copyright if they harm the copyright owner’s market or fail other fair use tests.

Q5: How does the three-step test affect copyright exceptions?

The three-step test requires that copyright exceptions apply only to “certain special cases,” not conflict with “normal exploitation” of works, and not “unreasonably prejudice” right holders’ interests. This international standard can restrict the scope of national copyright exceptions.

Q6: What are technological protection measures (TPMs) and how do they affect fair use?

TPMs are digital locks that control access to copyrighted works. While copyright law may permit certain uses under fair use or fair dealing, TPMs can technically prevent these uses. Anti-circumvention laws often make it illegal to bypass TPMs even for legitimate purposes.

Q7: How does copyright law apply to artificial intelligence and machine learning?

AI copyright issues are evolving rapidly. Recent court cases suggest that using copyrighted works to train AI models may sometimes qualify as fair use, but this depends on specific circumstances including the purpose of use, transformation involved, and market impact.

Q8: What is the Marrakesh Treaty and why is it important?

The Marrakesh Treaty requires countries to create copyright exceptions for blind, visually impaired, and print-disabled persons. It represents the first mandatory international copyright exception and demonstrates how international cooperation can balance copyright protection with human rights concerns.

Q9: How do educational institutions handle cross-border copyright issues?

Cross-border educational uses create complex legal challenges since copyright law is territorial. Online courses reaching students in multiple countries must consider different national copyright laws. This often requires either licensing content for all relevant jurisdictions or limiting access by geography.

Q10: What should educators know about contract override of copyright exceptions?

Publishers increasingly use license agreements that override statutory educational exceptions, particularly for digital materials. Educational institutions should carefully review license terms and consider whether they preserve necessary educational uses permitted under copyright law.

[…] on September 3, 2014, established several groundbreaking principles that continue to influence copyright law […]