The Challenge of Constitution Writing in Deeply Divided Societies

Constitution writing in deeply divided societies is one of the most complex and consequential tasks a nation can undertake. These societies are not just marked by differences in ethnicity, language, or religion, but by fundamental disagreements over the very identity and future direction of the state. The stakes are high: a constitution is not only a legal document but also a charter of national identity and a blueprint for coexistence. In deeply divided societies, the process of constitution writing can either pave the way for peace and democratic stability or deepen existing rifts and fuel further conflict.

Table of Contents

Why Constitution Writing in Deeply Divided Societies Is Unique

Unlike relatively homogeneous societies, deeply divided societies lack consensus on core values, symbols, and the vision of the state. This makes constitution writing in deeply divided societies a high-wire act, balancing the need for foundational clarity with the imperative to avoid alienating large segments of the population. The process is fraught with risk, as forcing a premature or rigid consensus can lead to political crisis, violence, or even the breakup of the state.

Key Features of Deep Division

- Non-divisible conflicts: These are conflicts over identity and vision that cannot be resolved by splitting resources or power.

- Competing visions: Deeply divided societies often have rival groups with mutually exclusive ideas about the state’s character, such as secular vs. religious, or nationalist vs. pluralist.

Theoretical Models: Why Standard Approaches Often Fail

In the literature, two ideal types of constitutions are often discussed:

- Nation-State Constitution: Based on a shared, homogeneous national or religious identity.

- Liberal-Procedural Constitution: Focused on shared democratic procedures, not on deep cultural or religious identity.

Constitution writing in deeply divided societies cannot easily adopt either model. The nation-state model demands consensus on identity that simply does not exist, while the liberal-procedural model requires a level of preconstitutional agreement on political liberalism that is rarely present in such contexts.

The Incrementalist Approach: A Pragmatic Solution

Given these challenges, constitution writing in deeply divided societies often turns to incrementalism. This approach avoids making clear, final decisions on divisive issues. Instead, it employs strategies such as:

- Avoidance of clear decisions

- Ambiguous or vague legal language

- Inclusion of contradictory provisions

By deferring controversial foundational decisions to future political processes, the constitution can reflect the reality of a divided society without forcing a false or unsustainable unity.

How Incrementalism Works

- Deferral to politics: Contentious issues are left for future parliaments or courts to resolve.

- Symbolic ambivalence: Contradictory or ambiguous language allows different groups to interpret the constitution in ways that align with their own visions.

- Gradual evolution: The constitution is seen as a living document, open to change as society evolves.

Case Studies: Constitution Writing in Deeply Divided Societies

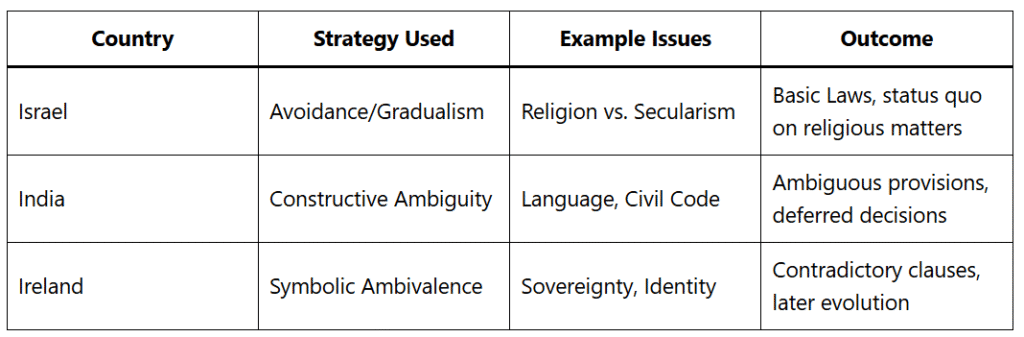

Israel: Avoidance and Gradualism

After its independence in 1948, Israel did not adopt a formal written constitution. Instead, it passed “Basic Laws” over time, mainly about government institutions, not foundational identity. The main conflict was between secular and religious Jews over the Jewish character of the state. The “status quo” arrangement maintained religious authority in certain areas (e.g., marriage, Sabbath), avoiding a direct clash. To this day, Israel continues to defer decisions on core identity issues, reaffirming the incrementalist approach to constitution writing in deeply divided societies.

India: Constructive Ambiguity

India adopted a written constitution but used ambiguous language on controversial issues:

- National Language: Hindi was made the “official language,” but English and 14 other languages were also recognized. The decision on a single national language was deferred.

- Uniform Civil Code: The constitution called for it but placed it in a non-binding section of constitution (Article 44) , allowing religious personal laws to continue.

These ambiguous solutions allowed India to function despite deep religious and linguistic diversity, demonstrating the effectiveness of incrementalism in constitution writing in deeply divided societies.

Ireland: Symbolic Ambivalence

The 1922 Irish constitution was drafted under British pressure and during civil war. The document included contradictory clauses to satisfy both Irish nationalists and British demands (e.g., references to both Irish sovereignty and British monarchy). This allowed for later evolution as political circumstances changed, eventually leading to full Irish independence. The Irish case shows how constitution writing in deeply divided societies can use symbolic ambivalence to create space for future consensus.

Central Features of Incrementalist Constitution Writing in Deeply Divided Societies

- Non-Majoritarianism: Foundational issues are not settled by majority rule but by consensus or deferral, to avoid deepening divisions.

- Non-Revolutionary Process: Constitution writing is seen as evolutionary, not a one-time revolutionary event.

- Representation of Division: Constitutions reflect the actual divided identity of the people, not a forced unity.

- Deferral to Politics: Controversial issues are left to be resolved by future political institutions, not entrenched in the constitution.

Strategies of Constitution Writing in Deeply Divided Societies

The Risks of Incrementalism in Constitution Writing in Deeply Divided Societies

While incrementalism offers a pragmatic path forward, it is not without risks:

- Potential Rigidity: Deferring decisions can lead to entrenched, hard-to-change arrangements (e.g., status quo in Israel, lack of Uniform Civil Code in India).

- Non-Liberal Outcomes: Ambiguous provisions, especially on religion, can harm liberal rights (e.g., women’s rights in family law).

- Institutional Tensions: Ambiguity can cause conflicts between courts and legislatures, as seen in India (Shah Bano case) and Israel.

Real-World Consequences

- In India, the non-justiciability of the Uniform Civil Code and the decision not to apply it to all religious communities meant that issues of family law remained in the hands of traditional religious authorities, often at the expense of women’s rights.

- In Israel, the lack of a civil system for family law has led to legal and social challenges, particularly for those who do not fit into established religious categories.

Constitution Writing in Deeply Divided Societies: Lessons and Best Practices

Embrace Gradualism

Constitution writing in deeply divided societies should be seen as a process, not an event. Gradualism allows societies to adapt as consensus evolves, rather than locking in decisions that may become untenable.

Prioritize Inclusion Over Uniformity

Rather than forcing a single vision of identity, constitutions should acknowledge and represent existing divisions. This approach fosters legitimacy and ownership among all groups, even if it means embracing ambiguity.

Use Ambiguity Strategically

Ambiguous or symbolic language can be a tool for managing disagreement, provided there are mechanisms for future resolution. However, care must be taken to ensure that ambiguity does not become a permanent obstacle to progress.

Build Strong Institutions

Incrementalist constitutions place significant pressure on political and judicial institutions to resolve deferred issues. Strong, independent institutions are essential for managing these challenges without undermining stability.

Constitution Writing in Deeply Divided Societies: The Path Forward

The experience of Israel, India, and Ireland demonstrates that constitution writing in deeply divided societies is possible, but it requires creativity, patience, and a willingness to accept imperfection. Rather than seeking to eliminate division, successful constitutions in these contexts recognize and accommodate it, creating frameworks that can evolve as society changes.

Key Takeaways

- Incrementalism is not indecision: It is a deliberate strategy to manage risk and maintain stability.

- Ambiguity can be constructive: When used wisely, it allows for future consensus-building.

- Constitutions must reflect reality: Legitimacy comes from representing the actual, often divided, identity of the people.

Conclusion: Constitution Writing in Deeply Divided Societies as a Model for the Future

As more countries grapple with internal divisions, the lessons from constitution writing in deeply divided societies are increasingly relevant. The incrementalist approach offers a way to craft constitutions that are both legitimate and adaptable, capable of guiding societies through periods of change and uncertainty. By acknowledging division and deferring contentious issues to the political process, constitution writing in deeply divided societies provides a pragmatic path toward peace, stability, and eventual consensus.

In the end, constitution writing in deeply divided societies is less about resolving every conflict at once and more about building a flexible framework that can accommodate change. It is a testament to the power of patience, pragmatism, and the enduring quest for a shared future.

Have you ever wondered how wide are the Uses of Research Public and Private

or Smart Contracts and Blockchain: Legal Issues and Implications for Indian Contract Law could be a great field of study.