The Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (PCA) is India’s cornerstone legislation for combating corruption in public administration. Enacted to replace the outdated 1947 Act, it provides a robust legal framework to address bribery, embezzlement, and abuse of power by public servants. This article explores the Act’s key provisions, landmark judgments, amendments, challenges, and its role in fostering transparency in governance.

Table of Contents

Objectives of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988

The PCA was designed to:

- Criminalize corruption: Define and penalize acts like bribery, misappropriation, and undue influence.

- Strengthen accountability: Hold public servants accountable for misconduct.

- Streamline prosecution: Establish special courts for speedy trials.

- Deter corrupt practices: Impose stringent penalties to discourage wrongdoing.

Key Provisions of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988

Definitions (Section 2)

- Public Servant: Broadly defined to include government employees, judges, university officials, and employees of public sector undertakings.

- Undue Advantage: Any gratification (monetary or non-monetary) beyond legal remuneration.

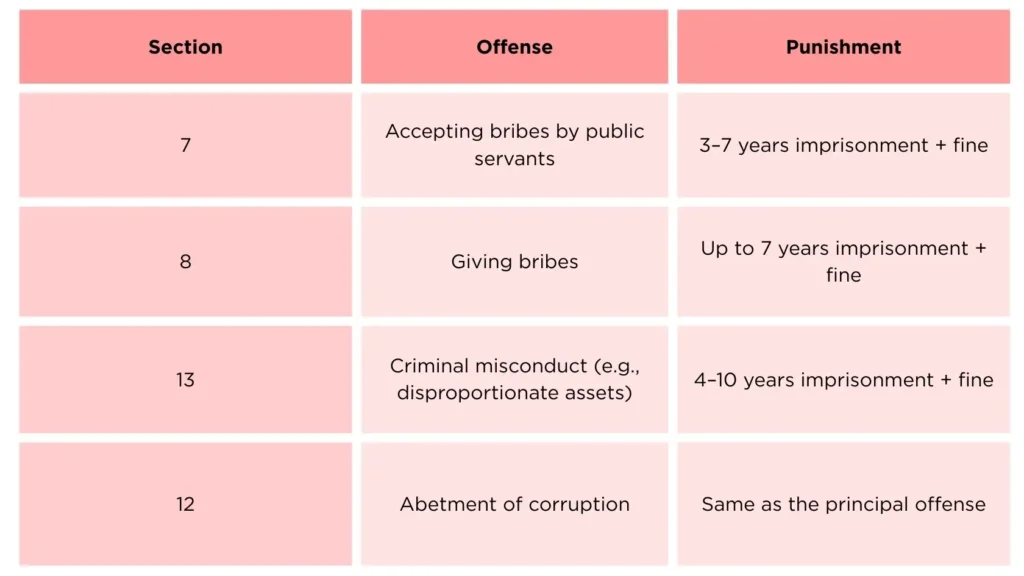

Offences and Penalties

Special Judges (Sections 3–6)

- Exclusive jurisdiction to try PCA cases.

- Empowered to conduct summary trials for expedited justice.

Presumption of Guilt (Section 20)

- If a public servant accepts illegal gratification, courts presume it was a bribe unless proven otherwise.

Sanction for Prosecution (Section 19)

- Mandates prior government approval to prosecute public servants, preventing frivolous cases.

Landmark Judgments Shaping the PCA

Subramanian Swamy v. Manmohan Singh (2012)

- Issue: Delay in granting prosecution sanction against a telecom minister in the 2G scam.

- Ruling: The Supreme Court mandated timely sanctions, emphasizing that delays undermine anti-corruption efforts.

P.V. Narasimha Rao v. State (1998)

- Issue: Whether MPs qualify as “public servants” under the PCA.

- Ruling: The Supreme Court affirmed that MPs are accountable under the Act, expanding its scope.

Vineet Narain v. Union of India (1996)

- Issue: Political interference in CBI investigations.

- Impact: The Court mandated CBI autonomy, leading to institutional reforms.

State of M.P. v. Ram Singh (2000)

- Ruling: The PCA must be interpreted liberally to serve its purpose of deterring corruption.

2018 Amendments: Strengthening the Framework

The Prevention of Corruption (Amendment) Act, 2018 introduced critical reforms:

- Criminalized bribe-giving: Earlier, only bribe-taking was penalized.

- Corporate liability: Commercial organizations can be fined if employees bribe public servants.

- Protection for coerced bribe-givers: Individuals forced to pay bribes can avoid punishment if they report within 7 days.

- Time-bound trials: Courts must complete trials within 2 years, extendable to 4 years.

Challenges in Implementation

Bureaucratic Delays

- Sanction requirements: Section 19 often delays prosecutions, as seen in the 2G scam case.

- Pending cases: Over 4,700 PCA cases were pending in courts as of 2021.

Weak Whistleblower Protections

- Despite the 2014 Whistleblowers Act, informants face threats due to poor enforcement.

Political Interference

- High-profile cases often stall due to influence over investigative agencies.

Evolving Corruption Tactics

- Digital bribes and offshore transactions complicate detection.

Impact and Way Forward

Achievements

- Increased convictions: Between 2015–2020, over 3,800 public servants were convicted under the PCA.

- Deterrence: The Act’s strict penalties have reduced overt bribery in sectors like income tax and railways.

Recommendations

- Fast-track courts: Dedicated benches to resolve PCA cases within 1 year.

- Strengthen whistleblower safeguards: Align with the K.S. Puttaswamy privacy judgment.

- Digital oversight: Use AI to track disproportionate assets and suspicious transactions.

- Public awareness campaigns: Educate citizens on reporting mechanisms like the CVC portal.

The Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 remains pivotal in India’s fight against graft. While landmark judgments and the 2018 amendments have bolstered its effectiveness, systemic challenges like delays and political interference persist. By addressing these gaps through judicial reforms, technological integration, and grassroots awareness, India can move closer to realizing its vision of a corruption-free governance system.

As former Supreme Court Justice J.S. Verma noted, “Corruption is not just a legal issue; it is a moral crisis that demands collective action.” The PCA provides the tools-now, their execution must match the urgency of the cause.

[…] the identity of a whistleblower must never be revealed to the accused during prosecution under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. The bench recognized that disclosing the identity could lead to embarrassment, intimidation, or […]