Introduction

The Stanford Prison Experiment stands as one of the most significant and controversial studies in the history of social psychology. Conducted by psychologist Philip Zimbardo in August 1971, this groundbreaking research aimed to explore how social roles and environmental factors influence human behavior. The experiment’s dramatic findings sparked decades of debate about ethics in research, the nature of human cruelty, and the powerful influence of situational variables on conduct. Today, as we examine The Stanford Prison Experiment through the lens of modern research ethics, its legacy continues to provoke essential questions about the boundaries of psychological research and the responsibilities of researchers to their participants.

The study’s importance extends far beyond academic circles. The Stanford Prison Experiment has informed our understanding of institutional abuse, from prison systems to military operations, making it a cornerstone reference for comprehending how ordinary individuals can engage in extraordinary acts of cruelty under specific circumstances.

Table of Contents

Background and Objectives of The Stanford Prison Experiment

Philip Zimbardo designed The Stanford Prison Experiment to investigate the psychology of imprisonment and the effects of perceived power on human behavior. The research emerged during a turbulent period in American history when concerns about prison violence and institutional abuse were at the forefront of public consciousness.

The primary objectives of The Stanford Prison Experiment were multifaceted. First, Zimbardo sought to examine whether the violence and abuse commonly observed in prison settings resulted from the inherent characteristics of prisoners and guards (the dispositional hypothesis) or from the prison environment itself (the situational hypothesis). This fundamental question would determine whether institutional problems stemmed from “bad apples” or “bad barrels”.

Zimbardo’s hypothesis centered on the belief that situational variables would prove more influential than individual personality traits in determining behavior. He theorized that the imposed social roles and environment of a prison would dominate participants’ individual personalities, causing them to exhibit more extreme behaviors than they would under normal circumstances.

also read about The Milgram Experiment 1963

Methodology and Research Design of The Stanford Prison Experiment

Participant Selection and Assignment

The Stanford Prison Experiment began with a carefully orchestrated recruitment process. Zimbardo placed advertisements in local newspapers, specifically the Palo Alto Times and The Stanford Daily, offering $15 per day to male college students willing to participate in a “psychological study of prison life”. From over 75 applicants, 24 physically and mentally healthy participants were selected after extensive screening that eliminated individuals with criminal backgrounds, psychological impairments, or medical problems.

The assignment of roles represented a crucial methodological element in The Stanford Prison Experiment. Participants were randomly assigned to serve as either prisoners or guards using a coin toss, ensuring that any behavioral differences observed could be attributed to the roles themselves rather than pre-existing personality differences.

Physical Environment and Setup

The research team transformed the basement of Stanford University’s psychology building into a realistic prison environment. This mock prison featured three small cells designed to house three prisoners each, a corridor serving as the prison yard, a closet for solitary confinement, and separate quarters for guards. The attention to detail in creating an authentic prison atmosphere was central to the experiment’s design, as Zimbardo believed that realistic conditions would produce genuine psychological responses.

Independent and Dependent Variables

Understanding the variables in The Stanford Prison Experiment is crucial for evaluating its scientific merit. The independent variable was the random assignment of participants to either prisoner or guard roles, while the dependent variable comprised the measured behavioral responses of participants in their assigned positions. This experimental design aimed to establish a causal relationship between role assignment and behavioral changes.

The Unfolding of The Stanford Prison Experiment

Initial Procedures and Realism

The Stanford Prison Experiment commenced with deliberately realistic arrest procedures designed to enhance the psychological impact on participants. Real Palo Alto police officers conducted surprise arrests at participants’ homes, complete with handcuffing, searches, and booking procedures at the police station. This dramatic beginning served to blur the lines between simulation and reality from the experiment’s inception.

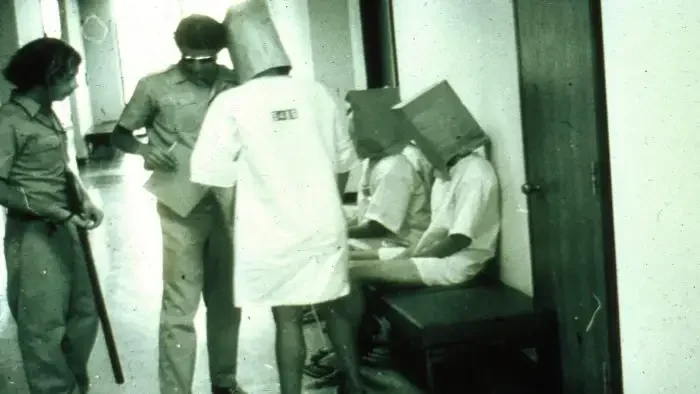

Prisoners were stripped, deloused, and given smocks and stocking caps to establish their powerless status and promote deindividuation. Each prisoner received an identification number to replace their name, further eroding their individual identity. Guards, conversely, wore military-style uniforms and reflective sunglasses that created an anonymous, authoritative appearance while carrying handcuffs, whistles, and billy clubs.

Rapid Deterioration of Conditions

The behavioral changes observed in The Stanford Prison Experiment occurred with shocking rapidity. Within 36 hours, the guards began implementing increasingly sophisticated systems of psychological punishment and control. They instituted arbitrary rules, conducted frequent prisoner counts at all hours, and created a privilege system that rewarded compliant prisoners while punishing those who resisted.

The prisoners’ responses were equally dramatic. Many began to internalize their roles completely, with some requesting “parole” and others experiencing severe emotional distress. Five prisoners had to be released early due to extreme emotional reactions, including uncontrollable crying, screaming, and rage.

The Experiment’s Premature End

The Stanford Prison Experiment was originally planned to last fourteen days but had to be terminated after only six days due to the severity of the abuse and psychological trauma experienced by participants. The decision to end the study came after Christina Maslach, Zimbardo’s former graduate student and future wife, confronted him about the ethical violations she observed. Her intervention proved crucial in highlighting how Zimbardo’s dual role as both researcher and prison superintendent had compromised his objectivity.

Research Ethics and The Stanford Prison Experiment

Ethical Violations and Concerns

The Stanford Prison Experiment raised numerous ethical issues that have fundamentally shaped modern research standards. The most significant concerns included lack of informed consent, failure to protect participants from psychological harm, and the absence of proper oversight mechanisms.

Participants were not fully informed about the potential psychological risks they would face. While they knew they would be assigned prisoner or guard roles, the extent of psychological manipulation and potential for trauma was not adequately communicated. The surprise arrests, in particular, violated participants’ informed consent, as they had not agreed to this specific procedure.

The experiment’s most serious ethical violation was the failure to protect participants from psychological harm. Philip Zimbardo himself later acknowledged that the study was unethical, stating that participants “did suffer considerable anguish” and that “five of the sample of initially healthy young prisoners had to be released early” due to extreme stress and emotional turmoil.

Zimbardo’s Dual Role Problem

A critical ethical flaw in The Stanford Prison Experiment was Zimbardo’s assumption of a dual role as both principal investigator and prison superintendent. This arrangement created a fundamental conflict of interest that compromised the study’s scientific integrity and participant welfare. As Zimbardo later admitted, “I was thinking like a prison superintendent rather than a research psychologist”, demonstrating how situational forces affected even the researcher himself.

This dual role prevented Zimbardo from maintaining the objective distance necessary to recognize when participant welfare was being compromised. Critics argue that this arrangement contributed directly to the prolongation of harmful conditions and the delayed termination of the experiment.

Modern Ethical Standards and The Stanford Prison Experiment

Following the revelations about The Stanford Prison Experiment and other controversial studies like the Milgram obedience experiments, the American Psychological Association significantly revised its ethical guidelines. Modern research standards would prohibit direct replications of The Stanford Prison Experiment, as Zimbardo himself acknowledged: “No behavioral research that puts people in that kind of setting can ever be done again in America”.

Scientific Validity and Criticisms of The Stanford Prison Experiment

Methodological Limitations

Recent scholarly analysis has revealed significant methodological flaws in The Stanford Prison Experiment that challenge its scientific validity. French historian Thibault Le Texier’s comprehensive investigation of the experiment’s archives uncovered evidence of researcher manipulation, incomplete data collection, and other serious methodological problems.

The study lacked essential scientific controls, including a control group, validated measurement instruments, and statistical analyses. These omissions make it impossible to draw reliable conclusions about the causal relationship between role assignment and behavioral changes.

The Coaching Controversy

Perhaps the most damaging revelation about The Stanford Prison Experiment concerns evidence that guards were explicitly coached to behave abusively toward prisoners. Le Texier’s archival research revealed that guards received specific instructions on how to create an atmosphere of powerlessness and were reprimanded when they failed to display sufficient dominance.

This coaching fundamentally undermines the experiment’s central claim that abusive behavior emerged spontaneously from role assignment. Instead, the evidence suggests that the observed behaviors were largely the result of explicit instruction rather than situational forces.

Demand Characteristics and Participant Awareness

The Stanford Prison Experiment suffered from significant demand characteristics, wherein participants modified their behavior based on their perceptions of what the experimenters expected. Many participants reported that they were consciously performing roles rather than genuinely experiencing the psychological states attributed to them.

Interviews with former participants revealed that they were aware of the artificial nature of the situation and were essentially “acting” their roles. This awareness contradicts the fundamental premise that participants became genuinely immersed in their assigned identities.

Replication Attempts and The Stanford Prison Experiment

The BBC Prison Study

The most notable attempt to replicate The Stanford Prison Experiment was conducted by psychologists Stephen Reicher and Alex Haslam in partnership with the BBC in 2002. This replication, known as the BBC Prison Study, failed to reproduce the original findings.

In the BBC study, prisoners did not become passive and submissive as they had in Zimbardo’s experiment. Instead, they organized collectively and “overthrew” the guards, demonstrating resistance rather than compliance. These contrasting results suggest that the original findings may not be as robust or generalizable as previously believed.

Lack of Peer-Reviewed Replications

Despite its fame and influence, The Stanford Prison Experiment has never been successfully replicated in a peer-reviewed study. This failure to replicate is particularly significant given the experiment’s prominent place in psychology textbooks and popular culture.

The broader replication crisis in psychology has highlighted the importance of reproducible findings. Studies that cannot be replicated may reflect methodological flaws, chance findings, or other factors that limit their scientific value.

Legacy and Impact of The Stanford Prison Experiment

Influence on Research Ethics

Despite its methodological limitations, The Stanford Prison Experiment has had a profound impact on the development of research ethics in psychology. The study’s ethical violations helped inspire significant reforms in human subjects protection, including strengthened institutional review board (IRB) procedures and more rigorous informed consent requirements.

These reforms have fundamentally changed how psychological research is conducted, ensuring better protection for research participants while maintaining scientific rigor. In this sense, The Stanford Prison Experiment serves as a cautionary tale that has ultimately benefited the field.

Applications to Real-World Situations

The Stanford Prison Experiment gained renewed attention following reports of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Zimbardo himself served as an expert witness in the court-martial proceedings, arguing that situational factors rather than individual pathology explained the guards’ behavior.

The experiment’s findings have also been applied to understanding institutional abuse in various settings, from schools and hospitals to corporate environments. While the study’s methodological problems limit the strength of these applications, its core message about the power of situational factors remains influential.

Educational Impact

The Stanford Prison Experiment continues to be widely taught in psychology courses despite growing awareness of its limitations. Many textbooks have failed to adequately address the study’s methodological problems, potentially misleading students about its scientific validity.

Recent efforts by scholars and educators aim to present a more balanced view of the experiment that acknowledges both its historical significance and its scientific limitations. This approach allows students to learn from the study while developing critical thinking skills about research methodology and ethics.

Modern Perspectives on The Stanford Prison Experiment

Contemporary Criticisms and Defenses

The Stanford Prison Experiment remains a subject of vigorous academic debate. Critics argue that the study’s methodological flaws and ethical violations invalidate its conclusions and that its continued prominence in psychology represents a failure of scientific self-correction.

Defenders of the experiment, including Zimbardo himself, maintain that despite its limitations, the study provides valuable insights into human behavior under extreme conditions. They argue that the dramatic nature of the findings, even if not perfectly controlled, demonstrates important principles about situational influences on behavior.

Lessons for Future Research

The Stanford Prison Experiment offers important lessons for contemporary researchers about the balance between scientific inquiry and ethical responsibility. The study demonstrates the need for robust ethical oversight, clear boundaries between researcher and participant roles, and careful consideration of potential harm to participants.

Modern research ethics emphasize the importance of minimizing harm while maximizing scientific benefit. This principle requires researchers to carefully weigh the potential knowledge gained against the risks to participants, a calculation that clearly favors participant welfare in cases of conflict.

Variable Analysis in The Stanford Prison Experiment

Understanding the Research Variables

The experimental design of The Stanford Prison Experiment centered on clearly defined independent and dependent variables that were intended to establish causal relationships between role assignment and behavioral outcomes.

The independent variable in The Stanford Prison Experiment was the random assignment of participants to either prisoner or guard roles. This variable represented the experimental manipulation that researchers controlled, serving as the presumed cause in the causal relationship under investigation. The random assignment was crucial for ensuring that any observed differences between groups could be attributed to the role assignment rather than pre-existing individual differences.

The dependent variable comprised the observed behaviors and psychological responses of participants in their assigned roles. Researchers measured various behavioral indicators, including compliance, aggression, emotional distress, and role internalization. These measurements represented the effects that researchers hypothesized would result from the role assignments.

Confounding Variables and Controls

Modern analysis of The Stanford Prison Experiment reveals numerous confounding variables that may have influenced the results beyond the intended independent variable. These include researcher expectations, participant awareness of being observed, the artificial nature of the environment, and explicit coaching of guards.

The lack of proper control conditions in The Stanford Prison Experiment represents a significant methodological limitation. A true experimental design would have included control groups that received different treatments or no treatment, allowing researchers to isolate the effects of role assignment from other factors.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Stanford Prison Experiment

What was the main purpose of The Stanford Prison Experiment?

The Stanford Prison Experiment was designed to investigate the psychological effects of perceived power and authority in a simulated prison environment. Zimbardo specifically wanted to understand whether the violence and abuse observed in real prisons resulted from the personalities of prisoners and guards or from the prison environment itself.

How long did The Stanford Prison Experiment last?

While originally planned to last two weeks, The Stanford Prison Experiment was terminated after only six days due to the severe psychological distress experienced by participants and the escalating abusive behavior of the guards. This premature termination highlights the intensity of the psychological effects observed during the study.

Were participants allowed to leave The Stanford Prison Experiment?

Yes, participants in The Stanford Prison Experiment retained the right to withdraw from the study. However, many prisoners seemed to forget or misunderstand this right, reinforcing their sense of imprisonment by telling each other there was no way out. Five prisoners ultimately left the study early due to severe emotional reactions.

What ethical standards did The Stanford Prison Experiment violate?

The Stanford Prison Experiment violated several key ethical principles, including inadequate informed consent, failure to protect participants from psychological harm, and lack of proper oversight. The study’s ethical problems were so severe that they contributed to major revisions in research ethics guidelines.

Has The Stanford Prison Experiment been replicated?

No peer-reviewed study has successfully replicated the findings of The Stanford Prison Experiment. The most notable replication attempt, the BBC Prison Study conducted in 2002, produced opposite results, with prisoners organizing to resist rather than submitting to guard authority.

What was Zimbardo’s role in The Stanford Prison Experiment?

Philip Zimbardo served both as the principal investigator and as the prison superintendent, a dual role that created serious ethical and methodological problems. This arrangement compromised his ability to maintain scientific objectivity and respond appropriately to participant distress.

Why is The Stanford Prison Experiment still important despite its flaws?

Despite its methodological and ethical limitations, The Stanford Prison Experiment remains important for its impact on research ethics reform and its insights into situational influences on behavior. The study serves as both a cautionary tale about research ethics and a starting point for discussions about institutional power dynamics.

Conclusion

The Stanford Prison Experiment occupies a unique and controversial position in the history of psychology. While the study’s dramatic findings about the power of situational factors to influence human behavior captured public imagination and influenced decades of research and policy, recent scholarship has revealed significant methodological flaws and ethical violations that challenge its scientific validity.

The evidence suggests that The Stanford Prison Experiment was less a rigorous scientific investigation than a dramatic demonstration designed to illustrate preconceived notions about institutional power. The coaching of guards, the lack of proper controls, and the researcher’s dual role all compromise the study’s ability to support its central conclusions about human nature and situational forces.

Nevertheless, The Stanford Prison Experiment has left an indelible mark on psychology and society. Its ethical violations contributed to essential reforms in research ethics that better protect human subjects today. Its dramatic narrative continues to provoke important discussions about institutional abuse, individual responsibility, and the conditions that foster cruelty or compassion.

As we continue to grapple with issues of institutional violence, abuse of power, and ethical research practices, The Stanford Prison Experiment serves as both a cautionary tale and a catalyst for deeper understanding. While we must reject its methodological shortcomings and ethical violations, we can still learn valuable lessons about the importance of rigorous research methods, ethical responsibility, and the complex interplay between individual and situational factors in human behavior.

The legacy of The Stanford Prison Experiment ultimately lies not in its specific findings, but in the conversations it continues to generate about power, ethics, and human nature. By examining this controversial study with both critical analysis and historical understanding, we can better appreciate both its contributions and its limitations while working toward more ethical and scientifically sound research practices in the future.

[…] The Milgram experiment 1963 continues to serve as both a landmark scientific achievement and a cautionary tale about the ethical responsibilities inherent in psychological research. Its findings about human obedience to authority remain profoundly relevant, while its ethical shortcomings have helped establish the rigorous standards that protect research participants today. For research ethics students, understanding both the scientific contributions and ethical failures of this seminal study provides essential insights into the ongoing challenge of balancing scientific progress with human dignity and welfare. Read about the Psychology’s Most Controversial Study The Stanford Prison Experiment […]

[…] Read The milgram Experiment 1963 and The Stanford Prison Experiment […]