Key Takeaway

The Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India turned a once‐insulated Supreme Court into a populist forum that bypassed rigid procedures, relaxed standing rules, and made the judiciary a central actor in India’s social revolution.

While the innovation opened court doors for the poor and marginalized, it also created a potent—and sometimes controversial—form of judicial power whose reach now spans environmental policy, corruption probes, and mega-infrastructure projects.

Since the Emergency (1975–77), the Indian Supreme Court’s innovative Public Interest Litigation (PIL) jurisdiction has dramatically expanded access to justice for marginalized groups and reshaped the judiciary’s role from passive arbiter to active socio-legal reformer.

The Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India spans its constitutional roots, landmark cases, procedural transformations, institutional challenges, and contemporary debates—demonstrating both its transformative potential and inherent tensions.

Table of Contents

Introduction: Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India

The 21-month Emergency (1975-77) left India’s higher judiciary discredited for upholding draconian detentions in ADM Jabalpur v. Shiv Kant Shukla. Reeling under public disdain, the Supreme Court sought a path to redemption. Its answer was Public Interest Litigation (PIL)—a jurisdiction conceived to give “the last resort for the oppressed and bewildered” a genuine home in court. The Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India thus began as a project of institutional self-repair, but soon evolved into a sweeping procedural revolution that remade constitutional law, judicial culture, and Indian politics alike.

Constitutional Roots: Directive Principles and the Social Question

At independence, India’s framers embedded a “social revolution” into Parts III and IV of the Constitution. Fundamental Rights (Part III) protected negative liberties, while Directive Principles (Part IV) charted socio-economic transformation. The tension between these strands became the great constitutional conflict of 1950-77: Parliament emphasized Directive Principles; the Court defended individual rights. The showdown culminated in Kesavananda Bharati (1973), which invented the Basic Structure doctrine while questioning Parliament’s sole claim to speak for “the people.” This doctrine laid conceptual groundwork for the Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India by legitimizing judicial guardianship of popular will.

Hence The Court’s turn to PIL was rooted in:

Populist Legitimacy: Post-Emergency, the Court sought popular sanction through rhetoric of “the people” and “last resort for the oppressed,” embracing a populist posture that mirrored and countered Indira Gandhi’s political discourse.

Directive Principles vs. Fundamental Rights: Embodied in the Constitution’s Part IV, Directive Principles authored a teleological vision of socio-economic justice, challenging the judiciary to operationalize “social revolution” beyond mere negative liberty.

Basic Structure Doctrine: In Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), the Court asserted its power to review constitutional amendments that violated the Constitution’s “basic structure,” inserting itself as guardian of the people over parliamentary majorities.

The Emergency Shock and Its Aftermath

Indira Gandhi’s Emergency suspended civil liberties, expanded preventive detention, and amended the Constitution to shield socialist measures from review (42nd Amendment). When the Court endorsed these moves, its legitimacy plummeted. After the Emergency’s fall, new constitutional amendments (44th) restored liberties, but the Court needed an imaginative tool to reconnect with citizens. Enter PIL.

Creating the People’s Court

Relaxing Locus Standi

In S.P. Gupta v. Union of India (1981), Justice P.N. Bhagwati declared that “procedure is but a handmaiden of justice,” relaxing standing so any public-spirited individual could file for others unable to approach the Court. This expansion of representative (class-based) and citizen (public duty) standing democratized access and catalyzed the Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India.

Letter Petitions and Evidence Commissions

Early PILs accepted letters and postcards as writ petitions—Hussainara Khatoon’s plea for under-trial prisoners arrived as a newspaper clipping. Judges appointed investigative commissioners to gather field evidence, replacing adversarial cross-examination with “socio-legal” fact-finding. Bandhua Mukti Morcha’s bonded-labour case epitomized this shift, ushering in an era of judge-driven inquiries.

Anti-Procedural Rhetoric

PIL champions denounced “Anglo-Saxon” technicalities as elitist relics. They invoked indigenous justice (lok adalats, nyaya panchayats) and socialist rhetoric to justify procedural improvisation. This populist language framed the Court as vanguard of a constitutional “social revolution,” intensifying the Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India.

Three Phases of PIL Jurisprudence

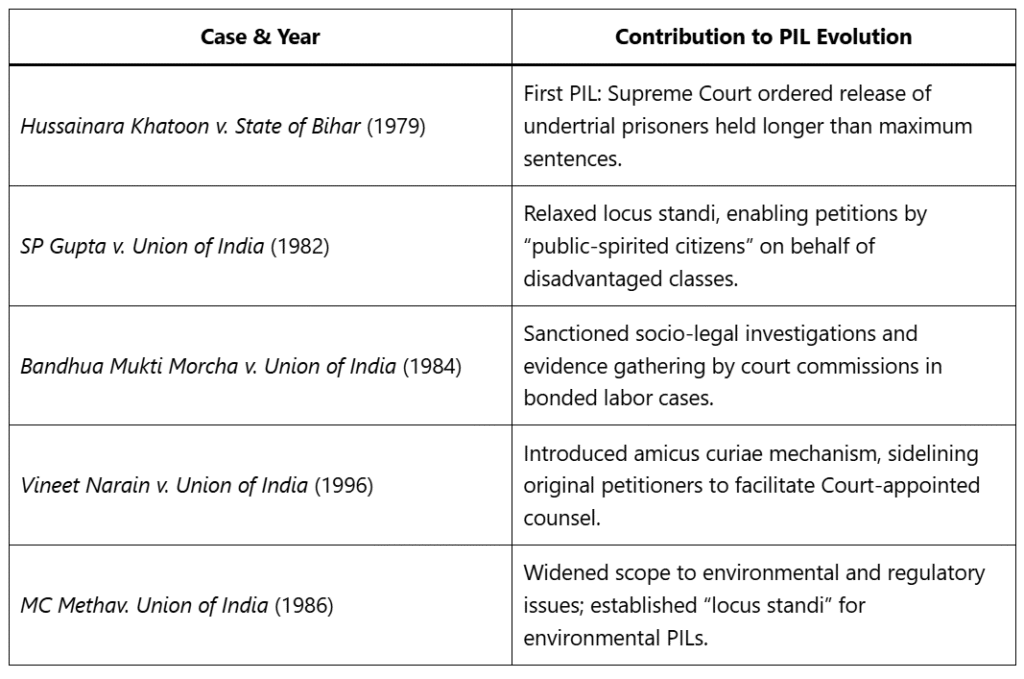

Phase I (Late 1970s–Mid-1980s): Social Rights and Liberation

Cases: Hussainara Khatoon (prisoners), Sheela Barse (women detainees), Olga Tellis (pavement dwellers).

Focus: fundamental rights of invisible groups; right to speedy trial; legal aid.

Method: letters treated as writs; on-site investigations; welfare-oriented directives.

Phase II (Mid-1980s–1990s): Environment and Development

Cases: M.C. Mehta (Ganga pollution, Taj trapezium), Godavarman (forest conservation).

Focus: ecological protection via continuing mandamus; judicial management of environmental policy.

Method: expansive interim orders; expert committees; appointment of senior advocates as amicus curiae who effectively shaped national policy.

Phase III (Mid-1990s–Present): Governance, Corruption, and Mega-Projects

Cases: Vineet Narain (CBI autonomy), 2G Spectrum, Coal Allocation, Interlinking of Rivers.

Focus: institutional integrity, anti-corruption, large infrastructure.

Method: suo motu petitions; displacement of original petitioners; Article 142 powers for “complete justice.”

Procedural Innovations and Their Consequences

| Innovation | Benefit | Unintended Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Relaxed locus standi | Broader access for poor & NGOs | Rise of “busybody” or politically motivated PILs |

| Letter petitions & flexible pleadings | Lowers entry barriers | Erodes certainty, invites forum shopping |

| Court-appointed commissions & experts | Fact-finding in inaccessible zones | Weakens adversarial testing, blurs roles |

| Continuing mandamus & supervisory orders | Ensures compliance over time | Judicial governance without political accountability |

| Amicus curiae dominance | Technical expertise | Marginalizes original petitioners, concentrates power in few senior advocates |

| Suo motu jurisdiction | Swift response to crises | Judges become both accuser and adjudicator |

These trade-offs illustrate how the Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India simultaneously democratized and personalized judicial power.

Landmark Moments in Detail

Hussainara Khatoon (1979)

Context: 40,000 under-trials were incarcerated longer than maximum sentences faced.

Outcome: Right to speedy trial read into Article 21; mass releases; triggers legal aid reforms.

Significance: Birth episode of Public Interest Litigation.

Bandhua Mukti Morcha (1984)

Context: Allegations of bonded labour in Faridabad stone quarries.

Procedure: Court-appointed commissioners; ex parte affidavits accepted.

Outcome: Directives for emancipation and rehabilitation; doctrinal approval of non-adversarial evidence.

Godavarman (1995–ongoing)

Context: Forest depletion nationwide.

Procedure: PIL morphs into “forest governance”; all interventions filtered by amicus and Central Empowered Committee.

Outcome: Blanket bans, clearance protocols, eco-sensitive zones—Court as de facto forest ministry.

Bhopal Settlement (1989)

Context: Industrial disaster with 3,000+ immediate deaths, long-term health fallout.

Twist: Court brokered secret settlement for $470 million (far below claims), invoking victims’ “suffering” to bypass procedure.

Repercussion: Showed how PIL legitimacy could legitimize deals opaque to affected communities.

Interlinking of Rivers (2002 suo motu)

Context: Presidential address referenced nationwide water networking.

Action: Court converted a monitoring I.A. in Yamuna PIL into a standalone petition, ordering executive to prepare project.

Scale: $100 billion; raises separation-of-powers concerns; illustrates limitless stretch of PIL.

Critiques: Populism, Overreach, and “Debased Informalism”

Scholars like Upendra Baxi celebrated PIL for “taking suffering seriously,” yet critics caution that the Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India has:

- Eroded procedural safeguards: Dispensations such as cross-examination deemed “inapposite” risk unreliable fact-finding.

- Marginalized litigants: Petitioners (e.g., Sheela Barse) removed; amicus or court assumes ownership, diluting participatory justice.

- Enabled judicial overreach: Courts now allocate coal blocks, set environmental standards, and design macro-economic projects.

- Created parallel governance: Continuing mandamus turns benches into supervisory agencies without electoral accountability.

- Breeds litigation entrepreneurship: Incentives for publicity, politics, or commerce under PIL banner.

Still, defenders argue that in a polity marked by executive vacillation and legislative gridlock, assertive courts fill vital gaps.

Procedural Innovations and Institutional Shifts

The Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India precipitated six core procedural reforms:

- Standing: Expanded beyond direct victims to any “public-spirited citizen,” democratizing access.

- Petition Form: Letters and postcards accepted as writ petitions, minimizing formalities.

- Evidence Gathering: Courtappointed commissioners and on-site inspections supplanted adversarial evidence rules.

- Non-Adversarial Process: Emphasis on conciliation and corrective orders over strict adversarial trials.

- Remedial Orders: Broad, policy-shaping directives (e.g., prison reforms, bonded labor eradication).

- Supervisory Role: Continuous judicial oversight, tracking implementation of orders through committees and amicus reports.

The Court’s self-fashioned “suomotu” powers further allowed it to convert media reports—such as “And Quiet Flows the Maily Yamuna” (1994)—into active PILs, institutionalizing judicial activism as a central mode of governance.

Impact and Reach

Between 1985 and 2019, the Supreme Court received over 923,000 PILs, averaging 26,379 filings per year, with a sharp rise post-2010 (from 24,823 in 1985 to 70,836 in 2019). Early PILs focused on prisoners, bonded laborers, and slumdwellers; contemporary PILs span environmental protection, human rights, governance, and socio-economic entitlements. Scholars attribute PIL’s reach to:

- Judicial willingness to embrace non-state actors (NGOs, activists).

- Middle-class judges adopting populist rhetoric.

- Expansion of substantive rights under Article 21.

Critiques and Challenges

The Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India has not been uncontroversial:

- Procedure Erosion: Critics argue PIL’s debasement of procedure—“debased informalism”—undermines rule-of-law safeguards and adversarial rigor.

- Disappearing Petitioners: Courts increasingly appoint amici curiae and legal committees, sidelining original petitioners and diluting democratic participation.

- Judicial Overreach: Expansion into policy and administration raises separation-of-powers concerns and questions about judicial competence in technical domains.

- Implementation Gap: Wide ambit of PIL orders often strains executive capacity, resulting in pendency and partial compliance.

Contemporary Debates and Reforms

As India’s polity and polity-economy evolves, the Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India faces new frontiers:

Legislative Oversight: Proposals for codifying locus standi and procedural norms to balance access with accountability.

Digital PILs: Social media campaigns prompting suo motu court suo motu actions.

Quantitative Backlogs: Overwhelming PIL docket burdens courts, necessitating triage mechanisms.

Collaborative Governance: Calls for institutionalizing structured public-policy processes rather than ad hoc judicial mandates.

The Keyword’s Journey in Contemporary Debates

Policy makers, activists, and scholars invoke the Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India when debating:

- Environmental clearances versus economic growth

- Anti-corruption drives (Lokpal, CBI autonomy)

- Judicial appointments and accountability

- Suo motu COVID-19 management orders

- Digital rights and privacy (e.g., Aadhaar, Pegasus)

Each controversy reopens questions first posed during the Emergency: Who speaks for the people? Through what procedures? With what checks?

FAQs

Q1: What triggered the Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India?

Q2: How did PIL alter traditional standing requirements?

Q3: What procedural changes define PIL jurisprudence?

PIL dispensed with strict petition formats, permitted letters as writs, appointed commissioners to gather evidence, and emphasized non-adversarial, corrective orders—effectively reengineering the adversarial trial model.

Q4: Which case first recognized environmental PIL?

MC Mehta v. Union of India (1986) pioneered environmental PIL, compelling closure of polluting industries and establishing the “public trust” doctrine under Article 21.

Conclusion: A Double-Edged Legacy

The Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India reshaped the relationship between citizens and the state. By transforming judges into interlocutors of public conscience, it democratized access to justice and propelled sweeping social change—from the release of under-trial prisoners to the protection of forests. Yet its populist energy also eroded procedural rigor, sidelined original petitioners, and enabled expansive judicial power with limited accountability.

Four decades on, PIL endures as India’s most distinctive legal innovation—one that continues to oscillate between emancipatory promise and paternalistic peril. As new crises—climate change, digital surveillance, pandemics—unfold, the future of Public Interest Litigation will hinge on reaffirming the delicate balance between judicial creativity and constitutional restraint, ensuring that popular justice does not mutate into its own deformation.

By tracing the historical arc, landmark precedents, procedural revolutions, and critical debates, this authoritative account of the Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India illuminates how PIL transformed Indian governance—empowering the judiciary yet provoking enduring contentions over its scope, legitimacy, and future trajectory.

Read more about The Right against Self Incrimination in India: Origins, Scope, and Contemporary Challenges

[…] The Rise of Public Interest Litigation in Post Emergency India: How a Constitutional Experiment Rede… […]