Have you ever wondered how researchers compare different legal systems, cultures, or organizations? The answer lies in understanding basic strategies in comparison, a methodical approach that helps us make sense of complex differences and similarities. Whether you’re studying law, business, or social systems, mastering the basic strategies in comparison can transform how you analyze information and make decisions.

Table of Contents

What Are Basic Strategies in Comparison, and Why Do They Matter?

Basic strategies in comparison refer to the systematic approaches and frameworks used to evaluate two or more things side by side. Rather than comparing randomly, these strategies provide structure and clarity. Think of them like a roadmap that guides your analysis from start to finish, ensuring you’re comparing the right things in the right way.

At its core, basic strategies in comparison help answer fundamental questions: What are we comparing? How are we comparing? What level of detail do we need? These strategies break down complex comparisons into manageable pieces, making them invaluable whether you’re analyzing business competitors, legal frameworks, or historical events.

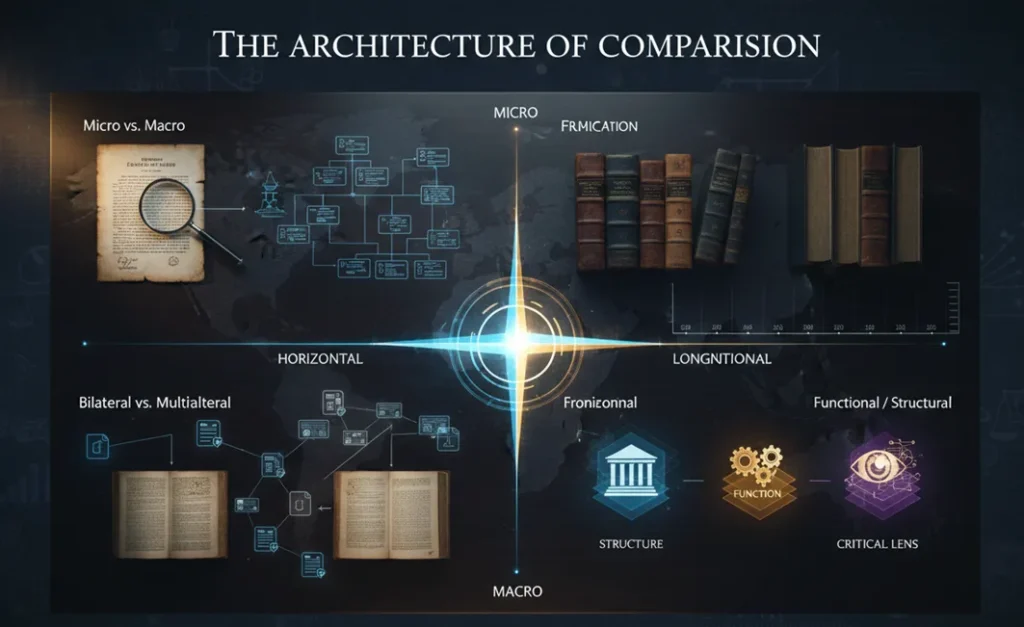

The Two Levels of Comparison: Micro and Macro

One of the foundational basic strategies in comparison divides analysis into two distinct scales: micro-level and macro-level comparison.

Micro-level comparison focuses on specific, detailed elements. Imagine you’re comparing how two countries handle marriage and divorce law. Here, you’d examine particular rules, specific court decisions, and individual legal institutions. Micro-comparison digs deep into one area, allowing researchers to understand nuances that broader perspectives might miss. The advantage? You can develop truly comprehensive knowledge about your chosen subjects.

Macro-level comparison, by contrast, zooms out to examine entire systems and their fundamental characteristics. Rather than studying individual marriage laws, you’d compare how two legal systems function overall—their core principles, historical development, and cultural foundations. Macro-comparison reveals patterns and big-picture differences that help us classify and understand entire legal families or organizational systems.

The beauty of these basic strategies in comparison is that they work together. A researcher studying micro-level details (individual laws) often needs macro-level understanding (the broader legal culture) to interpret what they’ve found. It’s like understanding individual words versus grasping the entire story—both perspectives are necessary for complete understanding.

Comparing Across Time: Longitudinal and Horizontal Approaches

Another critical dimension of basic strategies in comparison involves the time element. Should you compare systems as they exist today, or should you include their historical development?

Horizontal comparison focuses on the present moment. If you’re comparing how different countries currently handle climate change policy, you’re conducting a horizontal comparison. This approach is practical and useful for immediate decision-making, which is why courts and policymakers frequently use it.

Longitudinal comparison brings history into the picture. It examines how legal systems or organizations have changed over time, tracing ideas back to their origins. For example, comparing how inheritance laws have evolved in three different countries over the past hundred years would be longitudinal. This deeper basic strategies in comparison approach takes more time and effort but reveals why systems developed as they did and how ideas migrate between cultures.

Consider this: understanding why a particular law exists today often requires knowing where it came from. Did one country borrow it from another? Has it been modified? These questions are answered through the historical lens of basic strategies in comparison.

Quantity Matters: Bilateral and Multilateral Comparison

How many things should you compare? This straightforward question leads to important basic strategies in comparison decisions.

Bilateral comparison examines two systems in depth. Imagine comparing the court systems of just two countries in meticulous detail. You’d study their histories, legal philosophies, how judges are trained, and how cases actually function in practice. The payoff is extraordinary knowledge about those specific systems, though the findings may not apply broadly to other places.

Multilateral comparison studies three, five, ten, or more systems. This approach provides a wider lens and helps identify patterns that apply across multiple contexts. However, there’s a trade-off: the more systems you include, the less deeply you can examine each one. You might compare similar legal procedures in twelve countries but with less detail than a bilateral comparison would provide.

A useful rule of thumb in basic strategies in comparison: the more cases you study, the less depth you achieve, and vice versa. Choose your approach based on your actual goal. If you need deep understanding of two specific situations, go bilateral. If you need to identify broader patterns or test whether something applies generally, go multilateral.

Different Levels and Cultures: Horizontal and Vertical Comparison

Basic strategies in comparison also consider the structural relationship between what you’re comparing.

Horizontal comparison compares systems at the same level. Comparing legal systems of three neighboring countries, analyzing three competing technology companies, or evaluating three marketing strategies—these are all horizontal comparisons. You’re looking at equivalent entities to understand their differences and similarities.

Vertical comparison compares systems at different levels. This might mean comparing a national legal system with an international law framework, or analyzing how a global policy translates to local implementation. This approach is increasingly important in our interconnected world where supranational systems (like the European Union) interact with national and local ones.

Similarly, basic strategies in comparison recognizes that some analyses occur within the same culture while others cross cultural boundaries. Intracultural comparison (comparing systems within the same culture) is often easier because shared assumptions and language reduce misunderstandings. Cross-cultural comparison presents greater challenges but offers richer insights, since it requires you to understand genuinely different worldviews.

The Analytical Approaches: Functional, Structural, and Critical Comparison

When you move beyond simply describing differences, basic strategies in comparison offers three powerful analytical approaches.

Functional comparison asks: “How does each system solve the same problem?” Rather than comparing surface-level rules, functional comparison finds the underlying purpose. Two countries might solve the custody of children problem through completely different legal mechanisms—one through family courts, another through customary councils—yet both achieve the goal of protecting children. This basic strategies in comparison method is especially valuable when systems differ significantly, as it reveals what truly matters beneath different language and structures.

Structural comparison examines how things are organized and built. It looks at the architecture of systems—their formal organization, hierarchy, and how components relate to each other. This approach works well when comparing organizations, legal codes, or any systematically organized entities.

Critical comparison goes deeper to examine underlying assumptions, power relationships, and cultural foundations. Rather than accepting systems as neutral and objective, this basic strategies in comparison method questions why systems are structured as they are and what values they reflect or promote.

Five Core Methods That Support Basic Strategies in Comparison

Professional researchers use several specific tools within basic strategies in comparison:

Benchmarking measures performance against a standard or peer organization. If you’re comparing company efficiency, benchmarking shows how one company performs against others in the same industry.

SWOT Analysis examines strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats across options. This straightforward basic strategies in comparison tool is popular in business and strategic planning.

PEST Analysis evaluates political, economic, social, and technological conditions. This approach reveals how external factors differently affect the systems you’re comparing.

Cost-Benefit Analysis weighs the advantages and disadvantages of different options. Useful for evaluating economic aspects within basic strategies in comparison.

Statistical Comparison uses numbers and patterns to analyze similarities and differences, providing analytical precision when comparing measurable variables.

Common Mistakes in Comparative Analysis

Several pitfalls can derail otherwise sound basic strategies in comparison:

- Comparing incomparable things: Ensure you’re actually comparing equivalent elements. Don’t compare the structure of Company A to the marketing approach of Company B.

- Ignoring context: Systems exist within specific historical, cultural, and social contexts. Comparing legal rules without understanding their cultural background leads to misinterpretation.

- Using biased frameworks: Your own perspective naturally shapes how you compare. Effective basic strategies in comparison requires acknowledging your assumptions and actively trying to view systems from their own perspective, not just from yours.

- Focusing only on similarities (or only on differences): Good comparative work must highlight both. Systems may be simultaneously very similar in some respects and very different in others.

FAQ: Questions About Basic Strategies in Comparison

Q: Can I use these comparison strategies for everything?

A: Absolutely. Whether you’re comparing schools, recipes, legal systems, or business models, the fundamental principles of basic strategies in comparison apply. Adapt the specific methods to your subject matter.

Q: How do I choose between micro and macro comparison?

A: Ask yourself: Do I need deep detail about specific elements (micro), or do I need broad understanding of overall systems and patterns (macro)? Often, you’ll use both approaches together.

Q: Is it better to compare many systems or just a few?

A: That depends on your goal. Few systems (bilateral) allow deep analysis but limited generalization. Many systems (multilateral) enable pattern-finding and broader conclusions but less specific detail.

Q: How do language differences affect comparison?

A: Significantly. Terms can have different meanings in different languages and cultures. Good comparative work accounts for this by seeking native expertise and being transparent about translation choices.

Q: What’s the biggest mistake people make when comparing things?

A: Not defining clearly what they’re actually comparing. Before starting any basic strategies in comparison, establish your research question, your criteria, and what outcomes would answer your question.

Conclusion: Mastering Basic Strategies in Comparison

Understanding basic strategies in comparison transforms analysis from casual observation into systematic investigation. By choosing appropriate levels of analysis (micro or macro), deciding on your time perspective (longitudinal or horizontal), selecting your scope (bilateral or multilateral), and picking your analytical method (functional, structural, or critical), you create a rigorous framework for comparison.

Whether you’re analyzing legal systems, business competitors, educational approaches, or social policies, these basic strategies in comparison give you the tools to move beyond surface-level observations. You’ll identify genuine similarities and differences, understand the reasons behind them, and draw conclusions that actually matter. In an increasingly complex world where understanding multiple perspectives is essential, mastering basic strategies in comparison is an invaluable skill.

About Author

Jaakko Husa is a Finnish professor of law and globalisation at the University of Helsinki, and a leading scholar of comparative law. He specialises in comparative methodology, legal theory, and constitutional studies, and is author of “A New Introduction to Comparative Law” and “Basic Strategies in Comparison.”

Read more

- Module I: The Discipline of Comparative Law (Sessions 1-7)

- Session 1

- Session 2

- Session 3

- Session 4

- Sessions 5

- Session 6

- Session 7

- Module II:

- Module II: Methodology in Comparative Public Law (Sessions 8-14)

- Session 8

- Session 9

- Session 10

- Session 11

- Mark Tushnet, ‘Some Reflections on Method in Comparative Constitutional Law’, pp. 67-83 in Sujit Choudhry (ed.), The Migration of Constitutional Ideas (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Vicki C. Jackson, ‘Comparative Constitutional Law: Methodologies’, pp. 54-74 in Michel Rosenfeld & Andras Sajo (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law (Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Session 12

- Session 13

- Session 14