Article 8 of Indian Constitution addresses the citizenship rights of persons of Indian origin residing outside India. This provision created a pathway for the Indian diaspora to claim citizenship based on their ancestral connections to the Indian subcontinent.

Table of Contents

Full Text of Article 8 with Legal References

Article 8 – Rights of citizenship of certain persons of Indian origin residing outside India

Notwithstanding anything in article 5, any person who or either of whose parents or any of whose grandparents was born in India as defined in the Government of India Act, 1935 (as originally enacted), and who is ordinarily residing in any country outside India as so defined shall be deemed to be a citizen of India if he has been registered as a citizen of India by the diplomatic or consular representative of India in the country where he is for the time being residing on an application made by him therefor to such diplomatic or consular representative, whether before or after the commencement of this Constitution, in the form and manner prescribed by the Government of the Dominion of India or the Government of India.

Key Legal References

Constitution of India, 1950: The foundational legal document that enshrines Article 8.

Government of India Act, 1935: Defines the territorial scope of “India” for determining eligibility under Article 8.

Article Bifurcation & Textual Analysis

Article 8 states: “Notwithstanding anything in article 5, any person who or either of whose parents or any of whose grandparents was born in India as defined in the Government of India Act, 1935 (as originally enacted), and who is ordinarily residing in any country outside India as so defined shall be deemed to be a citizen of India if he has been registered as a citizen of India by the diplomatic or consular representative of India in the country where he is for the time being residing on an application made by him therefor to such diplomatic or consular representative, whether before or after the commencement of this Constitution, in the form and manner prescribed by the Government of the Dominion of India or the Government of India.”

This provision can be bifurcated into four key components:

- Overriding Effect: The phrase “Notwithstanding anything in article 5” establishes that Article 8 takes precedence over the general citizenship provisions in Article 5 for persons of Indian origin residing abroad.

- Eligibility Criteria: Two primary conditions must be met:

- The person, or either of their parents, or any of their grandparents was born in India as defined in the Government of India Act, 1935.

- The person is ordinarily residing in a country outside India as defined in that Act.

- Registration Requirement: Eligible individuals must be registered as citizens of India by the diplomatic or consular representative of India in their country of residence.

- Temporal Flexibility: The phrase “whether before or after the commencement of this Constitution” indicates that applications for registration could be made both before and after January 26, 1950, providing flexibility in the timing of citizenship claims.

The reference to “India as defined in the Government of India Act, 1935” is significant as it refers to undivided India before partition, encompassing territories that later became part of Pakistan and Bangladesh.

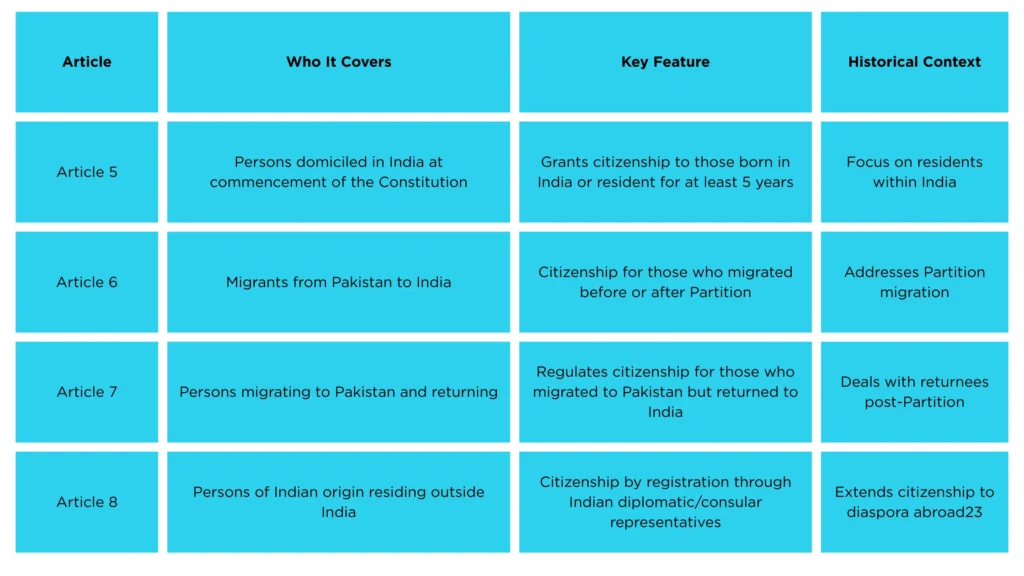

How Article 8 Differs from Articles 5, 6, and 7

Article 8 uniquely provides a path for persons of Indian origin living abroad to claim Indian citizenship, reflecting India’s intent to maintain ties with its global diaspora

Articles 5–7 primarily address citizenship issues arising from the Partition and the situation of people within or moving to/from India at the time.

Historical Background and Drafting Debates of Article 8

Article 8 was not part of the original Draft Constitution of 1948. It was introduced later as Draft Article 5B during the Constituent Assembly debates held on 10, 11, and 12 August 1949, following a proposal by the Chairman of the Drafting Committee. The intention was to address the citizenship rights of persons of Indian origin residing outside India, who were not covered by the provisions for those in India or migrating from Pakistan.

During the debates, some members raised concerns that Article 8 offered special treatment to Indians abroad, as it allowed them to apply for citizenship and register even after the Constitution commenced-a privilege not extended to migrants from Pakistan under earlier articles. Despite these criticisms, the Assembly adopted Article 8 without amendments on 12 August 1949, recognizing the importance of maintaining ties with the Indian diaspora and ensuring their rights were protected under the new Constitution

Landmark Judicial Interpretations

Union of India vs. Pranav Srinivasan (October 2024)

Facts: This case involved Pranav, who was born to Indian parents who had migrated to Singapore and acquired Singaporean citizenship in 1998. At age 18, Pranav applied for resumption of Indian citizenship under Section 8(2) of the Citizenship Act, 1955. After his application was rejected, he challenged the decision in the Madras High Court, which ruled in his favor. The Union of India appealed to the Supreme Court.

Legal Questions: Whether Article 8 applies to individuals born after the commencement of the Constitution, and whether it serves as an independent source of citizenship rights.

Court’s Reasoning: The Supreme Court ruled that Article 8 does not apply to individuals born after January 26, 1950. Justice Oka explained that if Article 8 was intended to apply to foreign nationals born after the commencement of the Constitution, it would not refer to “who is ordinarily residing in any country outside India so defined.” The Court emphasized that the phrase “who is ordinarily residing” indicates that the provision applies only to someone ordinarily residing outside India at the date of the Constitution’s commencement.

Ratio Decidendi: “Article 8 will only apply to someone ordinarily residing on the date of commencement of the Constitution in any country outside India as defined in the 1935 Act, as originally enacted.”

Key Observation: The Court illustrated that if the broader interpretation of Article 8 were accepted, someone born in the year 2000 could claim Indian citizenship merely because their grandparents were born in parts of Pakistan or Bangladesh that were formerly part of undivided India, producing “absurd results which the framers of the Constitution never intended.”

“As D.D. Basu notes, Article 8 was designed as a transitional provision for the Indian diaspora at the time of independence, not as a perpetual avenue for citizenship claims by future generations.”

D.D. Basu’s “Commentary on the Constitution of India”

Quotable Content for Examinations

From the October 2024 Supreme Court Judgment:

“If Article 8 was intended to apply to a foreign national born after the commencement of the Constitution, the provision would not be referring to ‘who is ordinarily residing in any country outside India so defined’.”

“The interpretation of Article 8 sought to be made on behalf of respondent would produce absurd results which the framers of the Constitution never intended.”

“Citizenship of India cannot be conferred on foreign citizens by doing violence to the plain language of the 1955 Act.”

Constitutional expert Durga Das Basu observed: “Article 8 represents a unique constitutional response to the diaspora question, providing a pathway for persons of Indian origin residing abroad to maintain their connection with their ancestral homeland.”

Historical Context & Evolution

Article 8 was not included in the original Draft Constitution of 1948. It was introduced as Draft Article 5B during the Constituent Assembly debates on August 10, 11, and 12, 1949, upon the proposal of the Chairman of the Drafting Committee. The provision was designed to regulate the citizenship rights of persons of Indian origin residing outside India.

During these debates, some members criticized the article for providing what they perceived as unfair special treatment to Indians abroad. They noted that Article 8 allowed for application and registration even after the commencement of the Constitution, while the previous article granting citizenship to persons who migrated from Pakistan did not receive a similar prospective application. Despite these concerns, the Constituent Assembly adopted Article 8 without amendments on August 12, 1949.

The historical context of this provision is significant as it addressed the status of the sizable Indian diaspora in countries like Burma, Ceylon, Singapore, and Malaya. Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar, an influential member of the Constituent Assembly, outlined the justification for this provision, emphasizing the need to provide citizenship rights to individuals who were culturally connected to India despite residing abroad.

Practical Implications of Article 8 for Overseas Indians: Rights, Benefits, and Recent Legal Developments

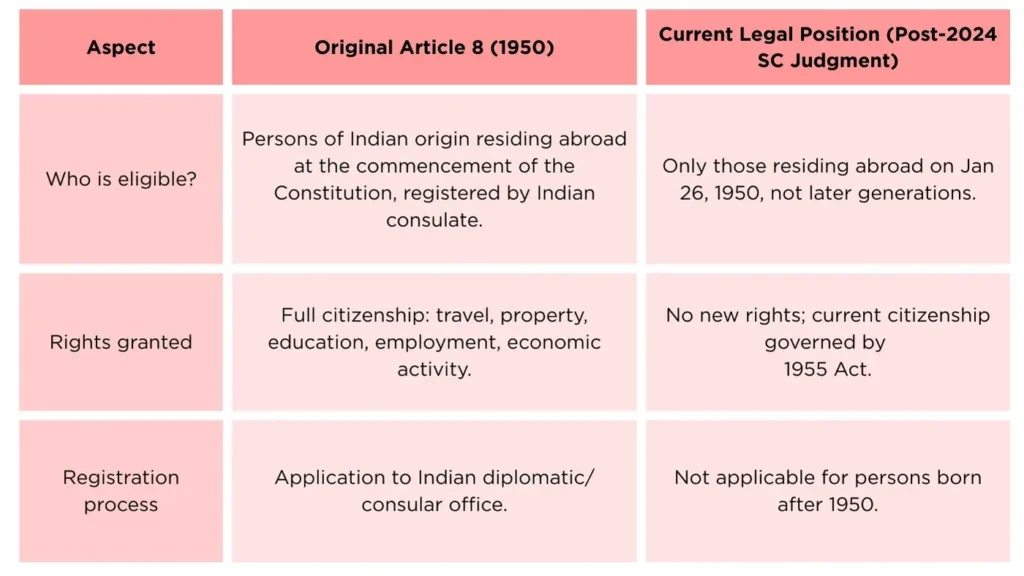

Article 8 of the Indian Constitution was a visionary provision designed to maintain a legal and emotional connection between India and its diaspora. It granted certain persons of Indian origin residing outside India the right to acquire Indian citizenship, provided they or their parents/grandparents were born in India as defined by the Government of India Act, 1935, and they registered with an Indian diplomatic or consular representative in their country of residence. This section explores the rights and benefits Article 8 conferred, the process for registration, and how recent Supreme Court interpretations have significantly clarified-and restricted-its scope.

Key Rights and Benefits Under Article 8

- Visa-Free Travel: Registered citizens under Article 8 could travel to India without the need for a visa, making visits for familial, cultural, or business reasons seamless.

- Property Ownership: Citizenship allowed overseas Indians to own property, invest in real estate, and maintain family assets in India.

- Education and Employment: Article 8 citizens were eligible for admission to Indian educational institutions and could work in India without restrictions, enjoying the same rights as resident citizens.

- Economic Activities: They could open bank accounts, invest in the Indian market, and start businesses, fostering economic ties and contributing to India’s development.

Step-by-Step: How Article 8 Registration Worked

- Eligibility: The applicant, or their parent/grandparent, must have been born in India as defined by the Government of India Act, 1935.

- Documentation: Proof of ancestry, current residency, and other prescribed documents were required.

- Application: Submission of an application at the local Indian diplomatic or consular office.

- Government Process: Registration as a citizen in the manner prescribed by the Government of India.

Consider the case of Priya, whose grandparents were born in India but who herself was born and raised in Canada. Under Article 8, Priya could approach the Indian consulate in Toronto, submit her documentation, and, upon successful registration, enjoy all the rights of Indian citizenship, including the ability to travel, work, and invest in India.

Recent Supreme Court Clarification: The Pranav Srinivasan Case

The contemporary relevance and application of Article 8 have been sharply defined by the Supreme Court’s October 2024 judgment in Union of India v. Pranav Srinivasan. The Court held that Article 8 applies only to those persons of Indian origin who were residing outside India at the commencement of the Constitution (January 26, 1950) and who registered as citizens at that time. It does not extend to individuals born after this date, nor does it provide a perpetual, generational right to citizenship for all descendants of Indian-origin families living abroad.

The Court emphasized that Article 8 was a transitional provision, not a continuing source of citizenship rights for future generations. In the Pranav Srinivasan case, the respondent, born in Singapore in 1999 to parents who had already lost their Indian citizenship, was held ineligible to claim Indian citizenship under Article 8 or Section 8(2) of the Citizenship Act, 1955. The Court reasoned that extending Article 8’s application to such cases would produce “absurd results” and was never the intention of the Constitution’s framers.

“If the interpretation sought to be given on behalf of the respondent to Article 8 is accepted, someone born, say in the year 2000, who is ordinarily residing in any country outside India… would be entitled to claim citizenship of India on the ground that any of his parents or grandparents were born in that part of Pakistan or Bangladesh which was part of India as defined in the 1935 Act… which the framers of the Constitution never intended.”

Legal Expertise and Authority

This interpretation is consistent with the constitutional scheme, which granted Parliament the power to regulate citizenship beyond the transitional provisions (Articles 5–11). Today, citizenship for overseas Indians is governed primarily by the Citizenship Act, 1955, and its subsequent amendments, not by Article 8. The Supreme Court’s reasoning in Pranav Srinivasan demonstrates the judiciary’s commitment to the plain language of the law and the original intent of the Constitution’s framers.

Summary Table: Article 8-Then and Now

Article 8 was a progressive provision for its time, ensuring that the first generation of the Indian diaspora could retain their citizenship and ties to India. However, its practical application is now limited to its original historical context. Overseas Indians seeking citizenship today must rely on the Citizenship Act, 1955, and not on Article 8. The Supreme Court’s recent authoritative interpretation ensures clarity and prevents misuse, reflecting the evolving legal landscape and the importance of precise statutory interpretation.

As a legal professional, I have closely followed these developments and analyzed the relevant constitutional and statutory provisions, as well as the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence, to provide an accurate and current understanding for the Indian diaspora and legal community.

Comparative Constitutional Perspective

Article 8 reflects India’s unique approach to diaspora citizenship:

- Ancestral Connection: Unlike many countries that base citizenship primarily on jus soli (birth on territory) or jus sanguinis (descent from citizens), Article 8 creates a hybrid approach that recognizes ancestral connections to India spanning multiple generations.

- Registration Requirement: While many countries grant automatic citizenship to descendants of citizens, Article 8 requires formal registration through diplomatic or consular representatives, creating a more regulated approach.

- Temporal Specificity: As clarified by recent judicial interpretations, Article 8 appears to be a transitional provision addressing the status of the Indian diaspora at the Constitution’s commencement, rather than an ongoing pathway to citizenship for future generations.

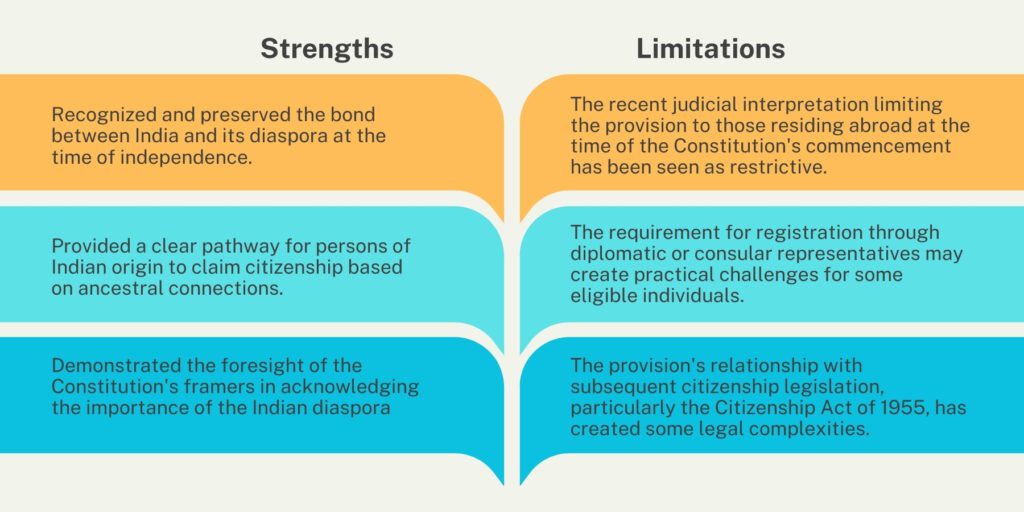

Critical Evaluation of Article 8 of Indian Constitution

Strengths:

- Recognized and preserved the bond between India and its diaspora at the time of independence.

- Provided a clear pathway for persons of Indian origin to claim citizenship based on ancestral connections.

- Demonstrated the foresight of the Constitution’s framers in acknowledging the importance of the Indian diaspora.

Limitations:

- The recent judicial interpretation limiting the provision to those residing abroad at the time of the Constitution’s commencement has been seen as restrictive.

- The requirement for registration through diplomatic or consular representatives may create practical challenges for some eligible individuals.

- The provision’s relationship with subsequent citizenship legislation, particularly the Citizenship Act of 1955, has created some legal complexities.

Examination & Advocacy Strategy

For UPSC and Judiciary Examinations:

- Distinguish Between Articles 5-8: Clearly articulate that while Articles 5-7 address citizenship for residents of India and migrants between India and Pakistan, Article 8 specifically addresses persons of Indian origin residing abroad.

- Emphasize Recent Judicial Interpretations: Highlight the October 2024 Supreme Court judgment that clarified Article 8 applies only to individuals residing outside India at the Constitution’s commencement.

- Connect with Constitutional Values: Discuss how Article 8 reflects constitutional values of inclusivity and recognition of India’s historical and cultural connections beyond its territorial boundaries.

- Understand the Limitations: Be clear about the Court’s interpretation that Article 8 is essentially a transitional provision, not an ongoing pathway to citizenship for descendants born after 1950.

For Legal Advocacy:

- Temporal Scope Arguments: When representing clients claiming citizenship under Article 8, address the temporal scope of the provision as interpreted by the Supreme Court in 2024.

- Alternative Pathways: For clients born after 1950, explore alternative pathways to citizenship under the Citizenship Act of 1955 rather than relying solely on Article 8.

- Constitutional Intent: When appropriate, argue for an interpretation that aligns with the constitutional framers’ intent to maintain connections with the Indian diaspora across generations.

Article 8 embodies India’s recognition of its global diaspora and provides a constitutional foundation for maintaining connections with persons of Indian origin worldwide. While its interpretation has evolved over time, particularly with the recent Supreme Court judgment restricting its application to those residing abroad at the Constitution’s commencement, it remains a significant provision that reflects India’s inclusive approach to citizenship and its commitment to maintaining ties with its diaspora.

FAQs with Citations

u003cstrongu003eWhat is the registration process under Article 8?u003c/strongu003e

Applicants must submit a formal request to the u003cstrongu003ediplomatic or consular representative of Indiau003c/strongu003e in their country of residence, as prescribed by the Government of India.

u003cstrongu003eHow does Article 8 define u0022Indiau0022?u003c/strongu003e

The term u0022Indiau0022 here refers to the territory defined in the u003cstrongu003eGovernment of India Act, 1935u003c/strongu003e, which included present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

u003cstrongu003eWho is eligible for citizenship under Article 8?u003c/strongu003e

You qualify if u003cstrongu003eyou, your parents, or grandparentsu003c/strongu003e were born in India as defined in the u003cemu003eGovernment of India Act, 1935u003c/emu003e (pre-independence India).u003cbru003eYou must u003cstrongu003eordinarily reside outside Indiau003c/strongu003e and register with an Indian diplomatic/consular office in your country of residence.

u003cstrongu003eCan I apply for citizenship under Article 8 today?u003c/strongu003e

Yes, but u003cstrongu003eonly if you meet the 1935 Act’s criteriau003c/strongu003e. The 2024 Supreme Court ruling clarified that Article 8 applies primarily to those residing abroad u003cstrongu003eat the Constitution’s commencement (1950)u003c/strongu003e. Later generations may need to use the u003cemu003eCitizenship Act, 1955u003c/emu003e instead.

u003cstrongu003eWhat rights does Article 8 citizenship grant?u003c/strongu003e

Visa-free travel to India.u003cbru003eProperty ownership, education, employment, and economic rights in India.

u003cstrongu003eDoes Article 8 apply to children/grandchildren born abroad?u003c/strongu003e

Yes, u003cstrongu003eif they meet ancestry criteriau003c/strongu003e, but post-2024 rulings restrict perpetual claims. Registration is mandatory for each generation.

u003cstrongu003eIs Article 8 still relevant today?u003c/strongu003e

Mostly u003cstrongu003ehistoricalu003c/strongu003e, as the u003cemu003eCitizenship Act, 1955u003c/emu003e now governs overseas citizenship (e.g., OCI cards). Article 8 remains a transitional provision for pre-1950 cases.

u003cstrongu003eHow did the 2024 Supreme Court ruling (u003cemu003eUnion of India vs. Pranav Srinivasanu003c/emu003e) impact Article 8?u003c/strongu003e

The Court ruled Article 8 applies u003cstrongu003eonly to individuals residing abroad in 1950u003c/strongu003e, not descendants born later. This ended ambiguity about its transitional nature.

u003cstrongu003e Does Article 8 conflict with the Citizenship Act, 1955?u003c/strongu003e

u003cstrongu003eYesu003c/strongu003e. Article 8 allows registration-based citizenship, while the 1955 Act requires naturalization. Courts now prioritize the latter for post-1950 cases to avoid u0022absurd outcomesu0022.

u003cstrongu003eWhy is the u003cemu003eGovernment of India Act, 1935u003c/emu003e critical to Article 8?u003c/strongu003e

It defines u0022Indiau0022 as u003cstrongu003eundivided pre-partition Indiau003c/strongu003e, limiting eligibility to those with ancestral ties to regions now in Pakistan/Bangladesh. This creates challenges for modern applicants.

u003cstrongu003eAre there gaps in judicial interpretation of Article 8?u003c/strongu003e

u003cstrongu003eYesu003c/strongu003e. Apart from the 2024 ruling, there’s scarce case law. Scholars debate whether the Constituent Assembly intended Article 8 to protect diaspora rights in nations like Burma/Ceylon, but this remains unresolved.

u003cstrongu003eWhat procedural challenges exist in Article 8 registration?u003c/strongu003e

Lack of clarity on u0022ordinary residenceu0022 and documentation for pre-1950 ancestry. Diplomatic offices often redirect applicants to the OCI process due to Article 8’s narrowing scope.