Imagine you’re at a dinner table in Lucknow, chatting with an old college friend about politics. You drop the term “Mandal case,” and suddenly the conversation turns serious. Why? Because Indra Sawhney v. Union of India shook the very foundation of India’s reservation policy back in 1992. It introduced the now-famous “creamy layer” concept, reshaped Article 15’s protective provisions, and fueled nationwide debates that echo even today.

At its core, the Mandal case tackled a tough question: How do you ensure social justice without undercutting the idea of equality? Should privileged members of backward classes share the benefits meant for the truly marginalized? This blog will walk you through the Mandal judgment step by step—what triggered it, the Supreme Court’s key findings, the evolution of Article 15 reforms, and how this case still influences everything from politics to campus diversity drives.

By the end, you’ll have a clear, jargon-free understanding of:

- Why the Mandal Commission’s recommendations mattered

- How the “creamy layer” rule operates in practice

- What Article 15 originally said—and how amendments and judgments expanded it

- Real-world lessons on balancing meritocracy and affirmative action

Whether you’re a law student, a policy wonk, or just a curious reader, you’ll find actionable insights, myth-busters, and FAQs to clear up common confusion. Ready? Let’s dive in.

Table of Contents

1. What Was the Mandal Case?

The term “Mandal case” refers to the Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992). Sparked by the government’s decision to implement the Mandal Commission’s recommendations, the case ultimately:

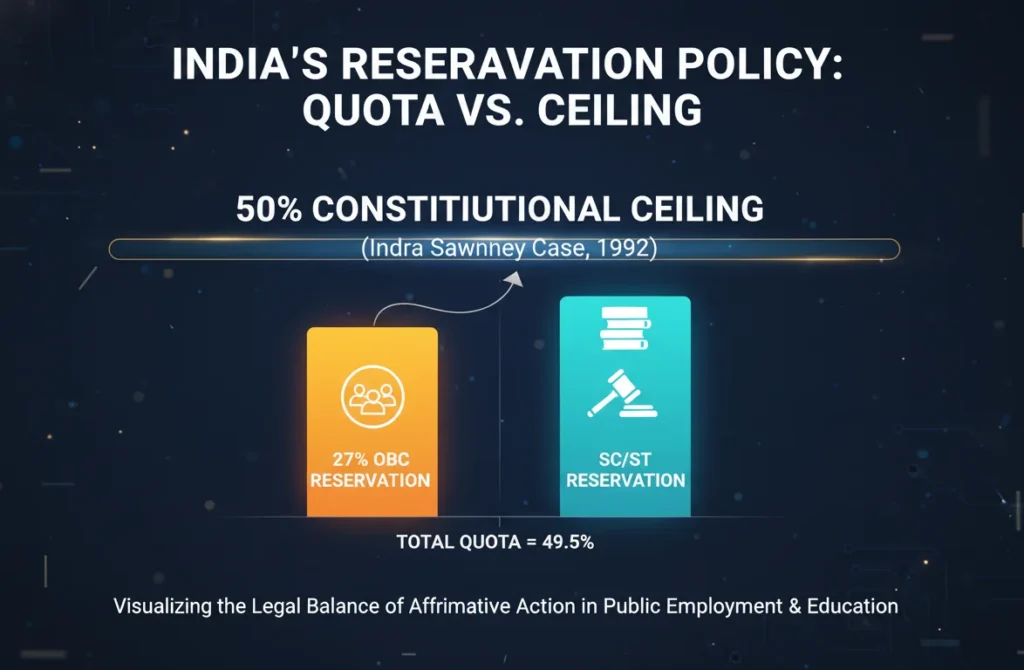

- Upheld 27% reservation for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in public employment.

- Capped total reservations at 50%, preventing the dilution of merit.

- Introduced the “creamy layer” principle, excluding affluent OBC members from quotas.

In essence, the Mandal case validated caste-based affirmative action as a constitutional tool, while setting important guardrails to ensure its fairness and efficacy.

2. The Constitutional Backdrop: Article 15 and Reservations

2.1 Article 15: Bare Text Provision

Article 15 of the Constitution of India reads:

“The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth. Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any special provision for women and children. Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any special provision for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.”

This clause serves two purposes:

- Non-discrimination: A shield against arbitrary state bias.

- Affirmative action: A sword to uplift marginalized groups.

2.2 The Evolution of Reservation Policy in India

- 1950: Constitution enshrines reservations for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

- 1951: First Amendment adds Article 15(4), empowering the State to advance “backward classes.”

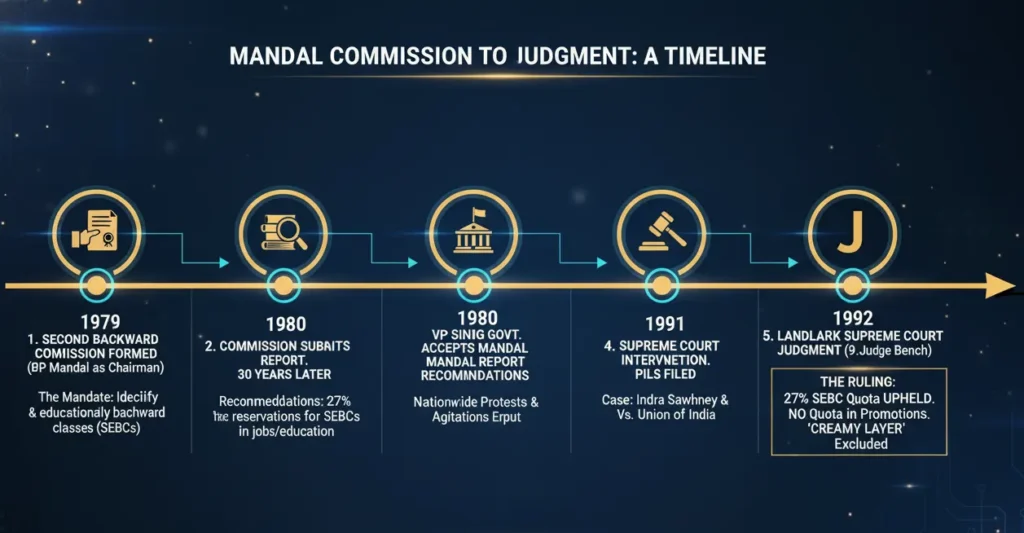

- 1979: Mandal Commission formed under B.P. Mandal to identify socially and educationally backward classes.

- 1990: Government announces 27% OBC reservation in public employment; protests erupt nationwide.

- 1992: Supreme Court delivers the Indra Sawhney verdict, balancing justice and equality.

Quick Takeaway: Article 15 is dynamic—its text is simple, but interpretation evolves with society’s changing needs.

3. The Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992) Case

3.1 Background and Trigger

Post-Independence India relied primarily on SC/ST quotas. By the late 1970s, backward classes beyond SC/ST felt excluded. The Mandal Commission recommended broadening reservations to OBCs—prompting intense debate on the nature and limits of caste-based benefits.

3.2 The Supreme Court Judgment

A nine-judge bench tackled key questions:

- Is caste a valid criterion for backwardness? Yes, as one indicator among many.

- Is there a cap on reservation percentages? Yes—a 50% ceiling, barring “extraordinary” circumstances.

- Can affluent backward‐class members claim quotas? No—they’re part of the “creamy layer” and thus excluded.

3.3 The Concept of “Creamy Layer” Introduced

The Supreme Court recognized that economic and educational advancement within OBCs—like high-earning professionals—means they no longer face the systemic disadvantages that quotas aim to correct. Hence:

- Creamy layer: The relatively affluent subgroup within OBCs.

- Exclusion criteria: Based on annual family income, parental occupation, and other factors revised periodically by the government.

Quick Takeaway: Excluding the creamy layer ensures reservation benefits reach the neediest families.

4. How the Court Balanced Equality and Social Justice

The Mandal verdict navigated a perceived conflict between:

- Article 14’s guarantee of equality, and

- Article 15’s authorization of special provisions for backward classes.

Rather than viewing them as opposing, the Court ruled that affirmative action advances equality by leveling a playing field skewed by historical disadvantages. The guiding principle became:

“Equality of treatment cannot mean treating unequals equally.”

This philosophy underpins many modern social justice debates worldwide.

5. Article 15 Reforms: Aftermath of the Mandal Case

5.1 93rd Constitutional Amendment (2005)

To cement Mandal’s legacy, Parliament inserted Article 15(5):

“Nothing in this article… shall prevent the State from making any special provision for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens… in educational institutions, including private unaided institutions.”

5.2 OBC Reservations in Education

Following this amendment, 27% OBC quota extended to:

- IITs, NITs, IIMs (2006 onwards)

- Central universities and professional colleges

5.3 Impact on Article 15(4) and 15(5)

- Ashoka Kumar Thakur v. Union of India (2008): Upheld OBC quotas in higher education; reaffirmed creamy layer exclusion in professional courses.

Quick Takeaway: Article 15’s scope broadened—from employment to education, public and private alike.

6. Real-World Impact of Mandal Verdict

6.1 Political Ramifications

- Rise of OBC-focused parties: Samajwadi Party, Rashtriya Janata Dal, and others.

- Shift in vote bank politics: Parties began targeting backward classes with tailored welfare schemes.

6.2 Social and Economic Shifts

- Educational access improved: More first-generation graduates from backward classes.

- Economic mobility: Enhanced entry-level public employment—but mixed results on long-term wealth accumulation.

6.3 Case Study: OBC Quotas in IITs and IIMs

- Admission share: OBC students regularly occupy their 27% seat share.

- Support challenges: Higher dropout rates initially led institutions to introduce bridge courses, mentoring, and remedial classes.

7. Common Misconceptions Around “Creamy Layer”

- Myth: Creamy layer applies to SC/ST too.

Truth: Currently only for OBCs; SC/ST quotas follow separate criteria. - Myth: Once you’re OBC, you remain eligible for life.

Truth: Crossing income/occupation thresholds can remove you from OBC status. - Myth: 50% reservation cap is inviolable.

Truth: Court allowed temporary exceptions in “extraordinary” cases—though none have exceeded 50% since.

8. Did You Know? Fascinating Facts About Mandal Case

- Student protests against Mandal saw over 30 self-immolation attempts in 1990 alone.

- The term “Mandal” was ranked among India’s most searched political topics in 1992.

- The case’s constitutional debate echoes in South Africa’s affirmative action jurisprudence.

9. Expert Tips & Advanced Insights

- Assess impact beyond quotas: Look at support services and socio-economic indicators.

- Monitor income thresholds: Family income caps for creamy layer are revised; stay updated via official gazette notifications.

- Explore intersectionality: Gender plus caste reservations may offer layered benefits—research state-level policies for SC/ST women.

10. FAQs on Mandal Case and Creamy Layer

- What is the current creamy layer income limit?

₹8 lakh per annum (family income), revised periodically. - Can private companies adopt Mandal quotas?

Not mandatory, but some PSUs and private sector firms implement OBC hiring targets voluntarily. - Has any state exceeded 50% reservations?

Tamil Nadu breaches 50% based on its unique social context and has been allowed by Supreme Court. - Is there a review mechanism for OBC lists?

Yes—State Backward Class Commissions regularly update lists and criteria. - Does Mandal affect educational scholarships?

Many government scholarships adopt the same creamy layer exclusion for fair distribution.

11. Checklists, Templates & Resources

OBC Eligibility Checklist:

- Annual family income ≤ ₹8 lakh

- Not in high-ranked government service or large landholding

- Clear supporting documents: income certificate, caste certificate

Article 15 Amendment Tracker Template:

| Amendment | Year | Key Change | Impacted Section |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | 1951 | Added (4) | Article 15(4) |

| Ninety-third | 2005 | Added (5) | Article 15(5) |

- “Article 14 VS Article 15

- Kesavananda Bharati

- Article 16: Equality of Opportunity in Public Employment

- Mandal Commission Final Report (1979)

- Supreme Court of India’s Indra Sawhney Judgment PDF

12. Summary and Key Insights

The Mandal case reaffirmed that social justice is integral to equality and that affirmative action must reach the truly disadvantaged. By introducing the creamy layer concept and capping reservations at 50%, the Supreme Court crafted a nuanced framework balancing merit and upliftment. Subsequent amendments widened Article 15’s scope, especially in education, while debates on thresholds and scope persist.

13. Conclusion + Call to Action

The Mandal verdict transformed India’s democratic fabric. Whether you view it as a necessary correction or an overreach, its influence on education, politics, and social equity is undeniable. What’s your take? Should the creamy layer principle extend to SC/ST reservations? Share your thoughts below, explore more constitutional insights on our blog, and subscribe for the latest expert analyses.

14. Author Bio

Adv. Arunendra Singh is a President award-winning, legal scholar and founder of Kanoonpedia. Currently at NLSIU Bangalore, he is recognized for pioneering content strategies at the intersection of law, technology, and digital education—helping legal startups and students achieve measurable growth in knowledge, user engagement, and academic success.

Whether you’re a student, lawyer, or someone curious about India’s journey toward inclusive justice, the Mandal case offers vital lessons. Keep learning, keep questioning, and let’s continue shaping a fairer society—one thoughtful debate at a time.