The Olga Tellis vs Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985) case is a cornerstone of Indian constitutional law, redefining the scope of Article 21 (Right to Life) to include the right to livelihood and shelter. This landmark judgment by a five-judge Supreme Court bench addressed the eviction of Mumbai’s pavement and slum dwellers, balancing urban governance with the fundamental rights of marginalized communities. Below, we analyse the case’s legal nuances, judicial opinions, and lasting impact.

Table of Contents

Factual Background of The Olga Tellis vs Bombay Municipal Corporation

In 1981, the Maharashtra government and Bombay Municipal Corporation (BMC) initiated a drive to evict pavement and slum dwellers under Section 314 of the Bombay Municipal Corporation Act, 1888, which allowed demolition of encroachments without prior notice. Over 50,000 people faced displacement, prompting journalist Olga Tellis and others to file a writ petition challenging the evictions as violations of Articles 19 (freedom of residence) and 21 (right to life).

Key Legal Issues in Olga Tellis vs Bombay Municipal Corporation

- Does the right to life under Article 21 include the right to livelihood and shelter?

- Can evictions be carried out without prior notice or rehabilitation?

- Are provisions like Section 314 of the BMC Act constitutional?

Arguments

Petitioners’ Case:

- Evictions without rehabilitation violate Article 21, as livelihood is tied to shelter.

- Section 314’s “no notice” clause violates natural justice and is arbitrary under Article 14.

Respondents’ Case:

- Pavement dwellers are trespassers with no fundamental right to occupy public spaces.

- The state has a duty to clear encroachments for public health and order.

Judicial Opinions and Reasoning

Majority Opinion (Chief Justice Y.V. Chandrachud, Justices A. Varadarajan, R.B. Mishra, and S. Murtaza Fazal Ali)

- Right to Livelihood as Integral to Article 21

- Key Reasoning:

- The Court rejected the narrow interpretation of Article 21 as merely a “right to exist.” Instead, it held that livelihood is inseparable from life itself, stating:“The right to life includes the right to livelihood. To deprive a person of their livelihood is to deprive them of their life.”

- This interpretation drew from Directive Principles (Articles 39(a) and 41), which obligate the state to secure citizens’ right to work and public assistance.

- Observation:

- The Bench emphasized that evicting pavement dwellers would force them into starvation, rendering Article 21 meaningless.

- Key Reasoning:

- Natural Justice and Procedural Safeguards

- Key Reasoning:

- While upholding Section 314 of the BMC Act (which allowed removal of encroachments without notice), the Court clarified that the provision must be used sparingly.

- Notice and hearing were mandated in all cases except emergencies, as arbitrary evictions violate Article 14 (equality before law).

- Observation:

- The Court noted that even trespassers deserve procedural fairness:“The rule of law demands that no one be condemned unheard.”

- Key Reasoning:

- Rehabilitation Mandate

- Key Reasoning:

- The state cannot evict slum dwellers without providing alternative accommodation, especially for settlements older than 20 years.

- Evictions without rehabilitation would amount to “forced destitution,” violating the right to dignity.

- Observation:

- The Bench directed the BMC to prioritize resettlement, citing Mumbai’s Slum Rehabilitation Authority as a model.

- Key Reasoning:

Dissenting Opinion (Justice M.P. Thakkar)

- Limits of Judicial Activism

- Key Reasoning:

- Justice Thakkar argued that the right to residence is not a fundamental right under Articles 19 or 21.

- He warned against judicial overreach into policy matters, stating:“Courts must not usurp the functions of the legislature or executive in urban planning.”

- Key Reasoning:

- Public Interest Over Individual Claims

- Key Reasoning:

- Pavement dwellers, as trespassers, cannot claim priority over public health and order.

- The state’s duty to clear encroachments for the “greater good” outweighs individual hardships.

- Observation:

- Justice Thakkar criticized the majority for creating an “unworkable precedent” that would hinder civic authorities.

- Key Reasoning:

Judgment Directives

The Court ruled:

- Evictions must follow due process: Notice, hearing, and rehabilitation plans are mandatory.

- No estoppel against fundamental rights: Petitioners cannot waive constitutional rights through prior agreements.

- Rehabilitation for long-standing slums: Settlements older than 20 years cannot be demolished unless land is needed for public use.

Critical Analysis of Reasoning

Dissent’s Caution:

Justice Thakkar’s dissent highlighted the practical challenges of judicial mandates in urban governance. His emphasis on separation of powers remains a cautionary note against excessive judicial activism.

Expanding Article 21:

The majority’s interpretation transformed Article 21 into a tool for socio-economic justice. By linking livelihood to dignity, the judgment recognized that poverty cannot negate constitutional rights.

Balancing State and Individual Interests:

While allowing evictions for public order, the Court imposed safeguards to prevent state overreach. This balance reflects the principle of proportionality in administrative action.

Legacy and Impact

- Precedent for Housing Rights: The case inspired subsequent rulings like Sudama Singh v. Delhi (2010) and the Haldwani Demolition Case (2023), reinforcing rehabilitation mandates.

- Policy Influence: Urban development schemes now prioritize resettlement, as seen in Mumbai’s Slum Rehabilitation Authority.

- Global Recognition: Cited internationally as a model for integrating human rights into urban governance.

Conclusion

The Olga Tellis vs Bombay Municipal Corporation case remains a beacon of judicial empathy, expanding constitutional protections for India’s urban poor. While the majority prioritized dignity over bureaucratic efficiency, the dissent underscored the complexities of judicial intervention in policy matters. For legal researchers, this case exemplifies the judiciary’s role as a custodian of fundamental rights in the face of rapid urbanization.

The right to life is not survival-it is the right to live with dignity, anchored in shelter and livelihood.

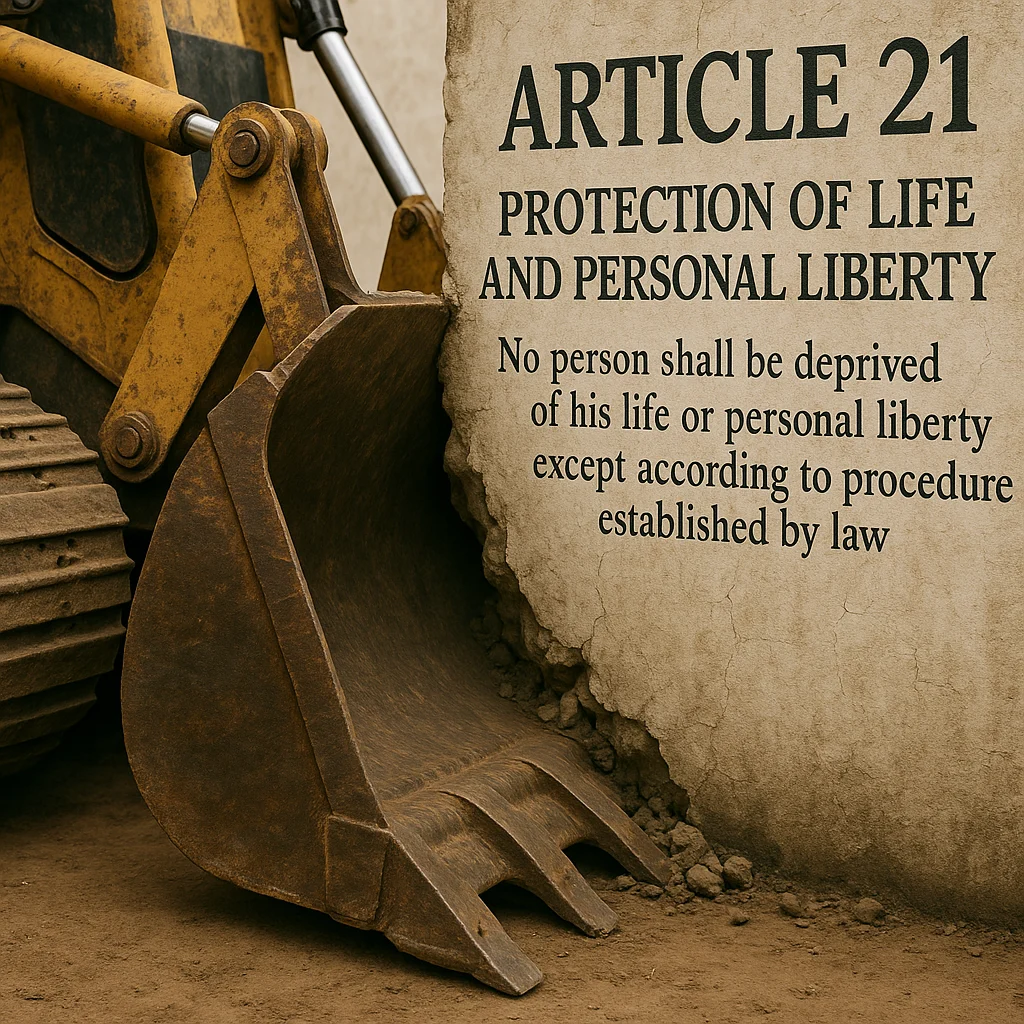

The Olga Tellis case stands as a testament to India’s constitutional commitment to protecting the right to life, livelihood, and dignity. Yet, the rise of “bulldozer justice” in recent years-where homes are demolished without notice, hearings, or rehabilitation-threatens to erode these hard-won safeguards. By bypassing due process and ignoring rehabilitation mandates, such actions blatantly violate Article 21, reducing the right to shelter to a hollow promise for marginalized communities.

The Supreme Court’s 2024 guidelines in Jamiat-Ulama-i-Hind v. Union of India explicitly prohibit arbitrary demolitions, emphasizing that lawful evictions require empathy, transparency, and accountability. Bulldozer-driven actions, however, often prioritize political expediency over constitutional morality, punishing entire families for alleged crimes of individuals and deepening societal inequities.

As citizens and custodians of democracy, we must demand that authorities adhere to the principles enshrined in Olga Tellis: the right to life is inseparable from the right to a home. Only by upholding these values can we ensure that the bulldozer-a symbol of development-does not become a tool of injustice, crushing not just concrete but the very foundations of our constitutional democracy.

The bulldozer must follow the rule of law, not replace it.

[…] Facts of the CaseIn 1981, the State of Maharashtra and the Bombay Municipal Corporation initiated a campaign to evict pavement and slum dwellers from Bombay, acting under Section 314 of the Bombay Municipal Corporation Act, 1888, which allowed removal of encroachments on public streets without prior notice. The petitioners, who were pavement dwellers, challenged the eviction, arguing it would deprive them of their homes and livelihoods, violating their fundamental rights under Articles 19 and 21 of the Constitution. Click to understand in deep. […]

[…] Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation: Recognized the right to livelihood under Article 21. […]

[…] ruling ignored precedents like Sudama Singh v. Delhi (2010) and Olga Tellis v. BMC (1985), which mandate surveys, hearings, and rehabilitation before […]

[…] in Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation, the Court’s protection of slum dwellers could have been grounded in administrative law […]